After Covid-19 drove students and teachers off campuses for the first time last year, and sent the economy spiraling, second-year law student Virak Satya decided to take a year off school in May, after about a month of struggling to concentrate during online classes.

By June, senior public administration major Soeun Lida considered pausing her university studies. She had made it through one term of remote classes, but was thinking about going to work in a garment factory to help support her out-of-work parents. Her father refused to let her drop out.

Trouble understanding lessons online and a poor internet connection pushed second-year computer science student Yan Sela to drop out of the Royal University of Phnom Penh in July.

With schools shut nationwide for the third time since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, and university enrollment down slightly last year, students say they have struggled with finances and months of online learning. While some undergraduates tell VOD they plan to finish their degrees, others have deferred their studies or are seeking tuition reductions as universities adapt to a new higher-education normal.

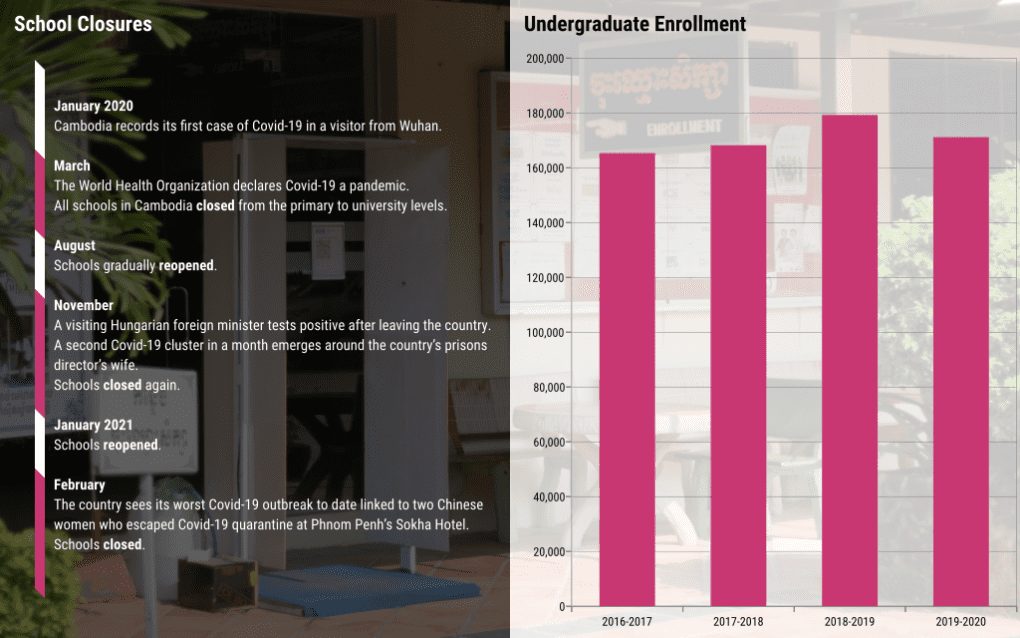

Undergraduate university enrollment nationwide dropped 4.5 percent from 179,258 students in the 2018-2019 academic year to 171,183 students in the 2019-2020 school year, according to Education Ministry figures provided by spokesperson Ros Soveacha.

The slight dip last year amid the pandemic follows consecutive rises in enrollment since the 2016-2017 school year, the ministry data shows.

Enrollment data for the 2020-2021 school year — which started later than usual due to pandemic-related closures — is not yet available, Soveacha says.

Schools from primary to university level closed for the first time during the pandemic in March last year and then reopened gradually beginning in August. Schools were shut again in November following the emergence of a new Covid-19 cluster and reopened in January, to kick off the delayed 2020-2021 school year.

But by February 23, three days after the ongoing “February 20” outbreak was announced, all schools were closed once again in Phnom Penh and Kandal, and then shut nationwide late last month.

Struggles of Online Learning

After months of back-and-forth between classroom and remote learning, some university students say they are hanging on till graduation day, while others have made the decision to delay their studies rather than continue to struggle with online learning.

Satya, 22, the second-year law student at the Royal University of Law and Economics, says he deferred his studies until June this year after a month of online classes last year, citing problems with internet connectivity, focusing during class and getting little out of online lectures.

“It is not the same as studying in an actual class [where] we have the chance to ask the teacher questions. But when we study online, it’s hard to ask a question to the teachers as sometimes when we start to unmute and talk, someone else unmutes and talks simultaneously,” Satya says.

“When we study physically in the class with the teachers, our mind is concentrated on the teachers,” he adds. “When moving to an online class, we don’t get to meet the teachers physically, therefore we are not so concentrated on the lecture.”

Lida, the public administration student, says even with a 50 percent scholarship at the University of Cambodia, it’s difficult to earn enough to pay $225 per term after her hours and salary from her restaurant cashier job were reduced amid the pandemic.

When her parents, who sell coconuts in Poipet along the Thai border, completely lost their income, Lida says she wanted to defer her studies to work in a garment factory where she could earn around $200 a month as a clothing inspector.

“I thought that learning online was not very good, and I saw that my family had no income, so I felt sorry for them and wanted to go back to work to earn money,” she says.

But her father told her to stay in school, especially since she was nearly finished with her degree.

“He did not want me to give up,” Lida says. “If I deferred, he considered that most other children, when they defer and have a family, they do not go to school anymore.”

This week, Lida says she decided to stop working and move back to her home province of Kampot because she can’t afford her living expenses in Phnom Penh.

Sela, the 21-year-old who left the Royal University of Phnom Penh (RUPP) in July, also says bad internet connections and trouble keeping up with lessons online, as compared to in the classroom, contributed to him leaving school.

“When studying online, we have too much freedom and not much control or pressure from the teachers,” he says.

“Sometimes the internet is very slow, the audio is not clear and while the class has already moved on to some other part, I am still stuck on this part, therefore it’s hard to understand.”

‘If I Give Up, I Will Lose’

Some university students have called for a reduction in tuition fees during the Covid-19 crisis while classes are conducted online.

Mao Chan Seyla, an economic development student at RUPP, asked for the government’s help to reduce tuition costs because her parents, who are shopkeepers, were earning less during the pandemic.

In addition to tuition fees of $500 per year, she says she spends $2 a week on mobile phone credit to use the internet for online learning.

“Because now I am in my third year, I can only continue to study until the end,” says Seyla, who works as an accountant while going to school.

“If I give up, I will lose because I have been studying for three years [already].”

That pain will be felt in economic terms later on as they enter the labour market as young adults.

Another RUPP student, Sokun Kanha, says she too could use some tuition relief.

The biochemistry student’s school fees are paid for by her sister who had to stop working at a factory to take care of their grandmother.

“I’m not happy because I pay for the whole year and do not go to the laboratory,” which is important to develop her skills, Kanha says.

Regardless of the costs, she has no plans to suspend her studies as she is nearly finished with her degree.

“[I] must complete the [school] year. If I defer [my education], all will be lost,” Kanha says. “If we learn online, it ends soon and we find a full-time job, because some jobs, they require full-time and they need a degree.”

RUPP’s vice-rector Tak Kean says no student has requested a reduction in tuition fees from the public university, so school leaders have not discussed the matter.

But in general, he says, the school allows some students to owe up to two or three semesters worth of tuition.

“It is not Covid, it is tradition,” if students request financial support, he adds.

Heng Vanda, board chairperson of the Cambodian Higher Education Association, says that during the pandemic, not only students but also universities and their faculty are affected.

If students are unable to pay their tuition fees, they should request support directly from their university, Vanda says.

“Some of the students, who are affluent, pay only $300, $400, $500 a year. I’m sure not too much,” he says, adding that schools also had to pay teachers and staff.

“How can we cut the salaries of teachers?”

Soveacha, the Education Ministry spokesperson, says the ministry encouraged universities and students to work together to address financial hardships.

The ministry “encourages education providers, education recipients and stakeholders to continue to discuss, negotiate and find appropriate solutions with a high level of understanding and mutual concessions,” Soveacha tells VOD. “Because all of them are affected by Covid-19.”

Investing in Education

According to U.N. Development Program resident representative Nick Beresford, the months students have spent out of school could have long-term economic and development impacts.

“Fewer university graduates in upcoming years will reduce the supply of skilled labor and slow Cambodia’s economic growth, and for those individuals that miss out on higher education, their lifetime earnings will be significantly reduced,” Beresford says in an email.

He adds that graduates with a bachelor’s degree earn about $402 a month compared to $296 a month for those with an associate’s degree and $240 for a technical or vocational school graduate.

In addition, UNDP research published in January estimates a nearly 4 percent decline in Cambodia’s Human Development Index last year, “mainly due to prolonged school closures and economic contraction,” according to Beresford.

“For Cambodia, this is equivalent to erasing all progress made in human development over the past four years,” he explains.

While the “economic pain” wrought by the pandemic is felt immediately, he says the larger loss is for children denied an education.

“That pain will be felt in economic terms later on as they enter the labour market as young adults — but without the education and skills they and this country increasingly needs,” he says.

I thought that learning online was not very good, and I saw that my family had no income, so I felt sorry for them and wanted to go back to work to earn money.

At the Royal University of Fine Arts (RUFA), while the number of enrolled students rose from about 2,500 in the 2019-2020 school year to 2,630 during the current year, academic affairs director Nhean Socheat says due to Covid-19 more students deferred their studies last year than the previous year, though the total was still only 11 students.

“I think this is because of the financial problems their families face during this crisis,” Socheat says, adding that he did not have dropout data for last year.

But after all high school students were given passing national exam grades last year, the art school received 100 to 200 more applications than usual for this school year, with most wanting to study architecture or interior design, he adds.

Sela, who left the IT program at RUPP last year, says he plans to apply to RUFA and major in music, but due to the current Covid-19 situation, he will wait to enroll.

As of Friday, the country has recorded more than 1,200 active cases of Covid-19.

“I want to change my major as I now seem to not like the computer science major anymore since I cannot understand the lessons [online],” Sela says.

“I haven’t enrolled in my new class yet,” he adds. “Probably next school year.”