Three communes in Kampot province have been turned into “Bokor city,” a new administrative area slated to become the province’s second municipality located in the midst of the 150,000-hectare Preah Monivong Bokor National Park.

A previously disclosed “master plan” for the city, announced by Land Management Minister Chea Sophara in 2019, said 9,000 hectares of the park would be used for residential areas, commercial zones, eco-tourism, administrative buildings, green spaces and water storage facilities.

The plans coincide with Sokha Hotel tycoon Sok Kong’s long-time proposal for development on Bokor Mountain — an idea he has floated since at least 2008, when he told reporters the project “will define me.” He received a 99-year lease for 20,000 hectares on the mountain in 2007.

Parts of the mountain were developed decades ago as a French colonial-era resort, and Kong has said he would stick to redeveloping those three plateaus spanning 14,000 hectares.

In a sub-decree dated March 16 and seen by VOD this week, the government established the Bokor city administrative area by grouping Teuk Chhou district’s Boeng Touk, Koh Touch and Prek Tnaot communes into a municipality. Administrative buildings would be in Boeng Touk, the decree says.

Moul Sokhom, chief of Boeng Touk commune, where the new city’s administration will be located, said she and her people were happy with the plan.

“They are happy to be included in a city, and the price of their land will increase,” Sokhom said. “When [they] become [part of] a city, they will be happy to have lights and everything.”

About 1,500 families currently lived in Boeng Touk, most of whom were garment factory workers, fishers, farmers and workers at salt farms, she said.

Economic activity was already visible, with land prices rising and local businesspeople planning to build condominiums and rental houses, she added.

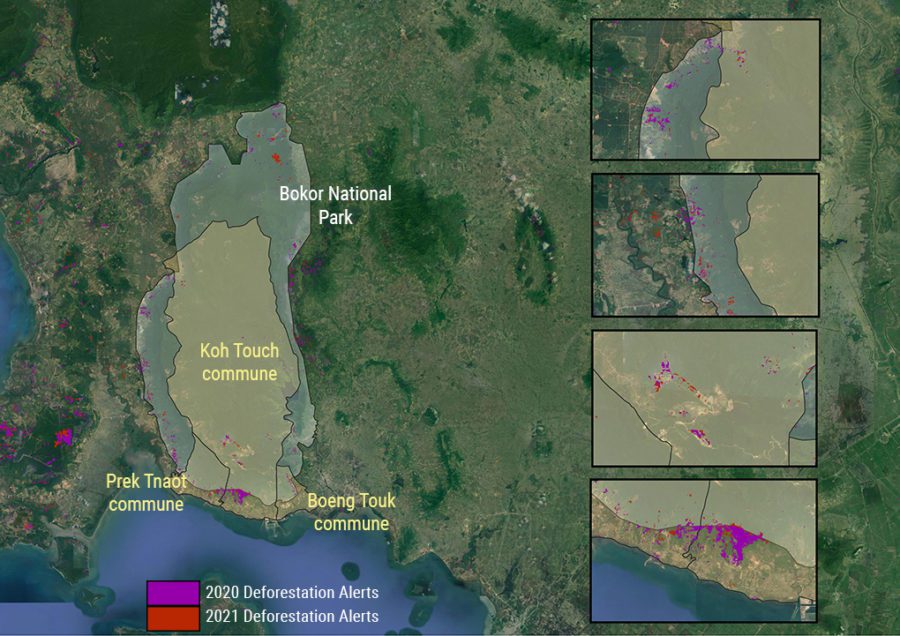

Asked about protected areas of the national park, Sokhom said there was some clearing happening despite authorities’ efforts to stop it. Her neighboring communes Koh Touch and Prek Tnaot had it worse, she said.

“Ordinary people do not dare much to do it. Mostly [it’s] the powerful people,” Sokhom said.

Koh Touch commune police chief Kuoch Chansuy said his commune had four villages at the base and the northern part of Bokor mountain.

There are thousands of hectares of land in his commune owned by companies, but there has not been any significant development on them yet, Chansuy said.

But the illegal clearing of forest land was happening up in the mountain, he said.

“When environmental officials go there, they escape,” he said. “I am worried about the clearing if there is no prevention.”

He said he didn’t think the clearing was related to the creation of a new city since it had been going on for some time.

Kampot provincial governor Cheav Tay said on Tuesday that the establishment of the Bokor municipality was part of a plan to create a tourist attraction in addition to Kampot city.

“We created a city to have a separate downtown to attract tourists,” Tay said.

Social analyst Meas Ny said he welcomed the creation of the municipality, but worried about the development being controlled by a private company.

Kong’s Sokha Real Estate company’s plans include the construction of thousands of houses and villas.

“The management in the Bokor area is not transparent,” Ny said. “The whole of Bokor city seems to belong to one company.”

Land Management Ministry spokesperson Seng Lot said on Wednesday that the establishment of the city was still in a preparatory stage.

Asked about the connection between the government’s master plan for the city and Kong’s announced development, Lot would only say generally that when there are people who own land and are planning constructions, it makes sense to create a municipality.

“It goes along together. It is one of the reasons to create the city,” Lot said.

On March 7, Land Management Ministry Sophara also spoke at a ground-breaking ceremony for Kong’s residential development on the mountain.

“This is an important territory and a resort so we have to support [it],” Sophara said. “If we support [it], it means that here — in every place and corner — [we] will see residences of our Cambodian people and our children of the next generation.”

The government’s master plan for the city, laid out in a June 2019 sub-decree, outlines a direction for establishing the town by 2035, with the plans to be adjusted every five years based on social and economic needs.