O’REANG DISTRICT, Mondulkiri — There was no need for fences in the past, says Tha Vy, 40, a former farmer who now takes up piecemeal jobs, picking pepper for other farmers or assisting on construction sites, as she’s doing in the late afternoon heat in February.

Brick walls and barbed wire divide Pu Rang village now, she says. When an outsider buys up the peak of a hillside, the local predominantly Bunong residents often can no longer even get to their traditional farmlands.

“People used to be able to go anywhere we wanted,” she says. Now, “it’s like locking us in a house.”

Life for the Bunong indigenous residents of Pu Rang village is changing fast. On one side are community members working to preserve the culture and land, including seeking a communal land title — a process stalled at the Land Management Ministry. On the other, a Justice Ministry official has been caught allegedly threatening locals to sell hundreds of hectares, part of a heightened thirst for land as prices rise. More than half of the farmland in Pu Rang has now been sold, locals say.

Last year, Vy was ready to take up farming again after tending to her mother’s health for about three years. Local farms are often separate from residences, typically rotational, and sometimes in steep or hard to access locations. Vy went to her family’s 4 hectares, about 1.5 km from her house, only to find barbed-wire fencing around it.

The village chief tried to compensate her after she discovered the lost land, she says, but she refused, instead complaining to commune and district authorities.

“They wanted to give $1,000 to 2,000 to compensate [me], but I said I didn’t want it,” she says. “I don’t want to make compromises with anyone because this is my farmland.”

Since 2018, the village’s land has been in high demand, Pu Rang community representative Nhak Srev says.

He suspects the demand has to do with a proposed airport development in the province — which the government hopes will begin construction next year — as well as the general rise in prices for provincial land.

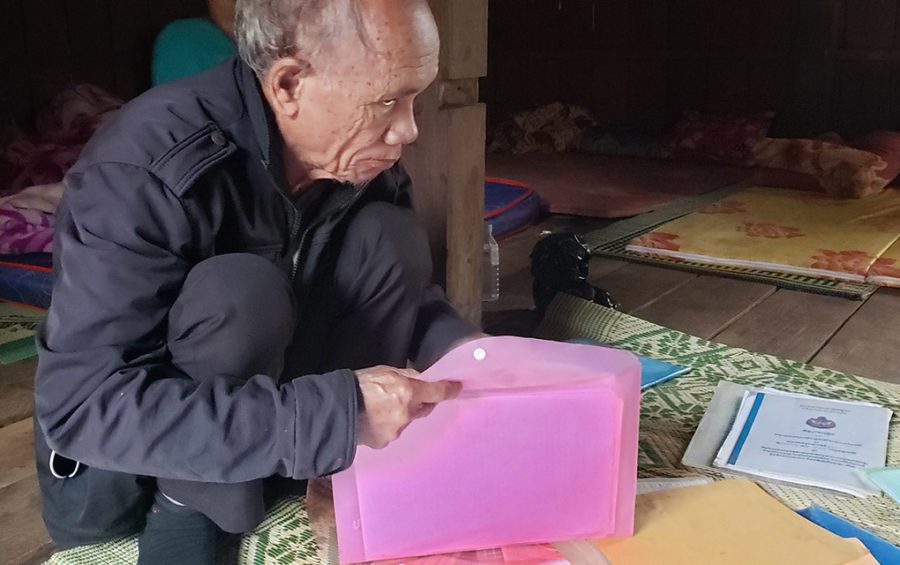

Srev keeps several plastic folders filled with the recent complaints he’s filed about land loss to all levels of government, from the village chief to a letter requesting intervention from Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Scattered among his files is recognition of the Bunong community in Pu Rang village by the Interior Ministry as well as approvals for the village’s communal land rights from the rural development and environment ministries. However, the Land Ministry never completed the final step: surveying the area and then issuing a land title.

Pu Rang village community leader Nhak Srev opens up folders holding multiple complaints he filed and documentation from the village’s communal land title application, in Mondulkiri province’s O’Reang district on February 13, 2021. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen/VOD)

A fallen sign advertising the Pu Rang village Justice Service Center, in Mondulkiri province’s O’Reang district on February 12, 2021. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen/VOD)

Injustice Official

In the middle of 2019, Srev says his community took up a case against one man: an undersecretary for the Justice Ministry in Phnom Penh.

Srev and the 55 villagers he represented filed a complaint in July 2019 against Seng Sovannara after the undersecretary of state allegedly threatened to jail indigenous villagers for not relinquishing 472 hectares of land.

One month later, Prime Minister Hun Sen ordered Sovannara to be removed from his post for “unspecified land issues in Mondulkiri province,” an official said at the time.

When Srev was initially filing complaints, he did not realize Sovannara had claimed land from neighboring Bunong villages too, not to mention nearly 1,000 hectares of Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary in Mondulkiri’s Koh Nhek district.

“We didn’t realize that other communities also filed complaints against him,” Srev says, saying he found out only after filing his community’s complaint letter.

Though Sovannara was jailed and relinquished his land, Srev says villagers continued selling the land that the official had tried to occupy. Srev believes that 50 percent of the village’s farmland has been sold, though it could be as much as 70 percent.

“Next year, there will be no more farmland. They will sell it all,” he says. “If the village chief can stop it, we can keep some land. But if not, it’s finished.”

Kreung Tola, a Bunong indigenous activist who frequently campaigns against Mondulkiri province officials for corruption in land and deforestation, says the complaints stretch across the province, its indigenous territories and protected areas.

The national government last year ordered the province to remove 10 of its officials, including the governor and a senator from Mondulkiri, for illegal land grabbing, but Tola described this as a shallow attempt at reform.

“Summoning officers and [court] cases is just a show to draw support from the public,” he says.

Threat to Culture

When reporters meet Srev at a friend’s house in February, Sorin Bunthoeun, a resident of neighboring Pu Chiang village, says he heard from village officials in early February that the land that they use for burial grounds will be sold.

“They say we have to dig up our ancestral graveyards, but we can’t do that,” Bunthoeun says.

For now, Srev says he continues to voice his opposition when community members announce that they will sell their land. He says he is not sure if it will have an impact, but he will continue to file complaints until someone tells him to stop, or the village sells all its land.

“If the king and prime minister say this community has no rights and should be dissolved, then I will dissolve it,” he says.

Srev expresses regret that members of the community are willing to leave, after they spent so much time trying to set it up.

“It takes time to make the community statute of regulations,” he says. “We did it thoroughly through many processes, but they just want to move out and destroy it.”

“If you want to be out of the community, you can be free, but you can’t take the land with you,” he says.

Rising land prices and expenses likely play a part in their decisions, as well as aggressive brokers, Srev says. Often, as local officials approve soft titles and land sales, the community only finds out when fences rise, he says.

The Pu Rang village chief could not be reached, but Nhok Nhong, chief of neighboring village Pu Chiang, says he knows very little about the sale of land within his territory. He says he is only alerted when residents make small transfers of 2 hectares or less, and even then he only finds out when someone starts occupying that land.

Vy, the former farmer, says the village gathered in protest when they learned last year that their spirit forest was sold to a buyer. But nothing changed, she says.

Between the loss of the forest and their rotational farmland, the Bunong community is losing its livelihood and way of life, Vy says. Community members started borrowing money only in the last four or five years, and now she worries because many, including herself, have lost the farms they used for income.

“In the past we didn’t need to know what we earned. Before, we relied on the forest,” Vy says. “The situation is different now.”

The land itself is hurting too as changes sweep across the village, she says. “Before, there was no Forestry Administration, no environmental protection, but there was no losing forests, loss of animals,” Vy says. “The animals would move as we rotate.”

Vy says the community isn’t going to be able to stand up to wealthier buyers from outside the village or province.

“People who have money rise up, while the ones without money stay down.”