The businesswoman who received more than 10 hectares of one of Phnom Penh’s “last lakes” Boeng Tamok from the government, raising questions around transparency and accountability, is the daughter of Land Management Minister Chea Sophara.

Fishers around the lake — some of whom have been evicted with their families — say they are angry and scared as landfilling now proceeds in full swing. They are also “speechless” over government officials taking the public lake that locals depend on and giving it to themselves.

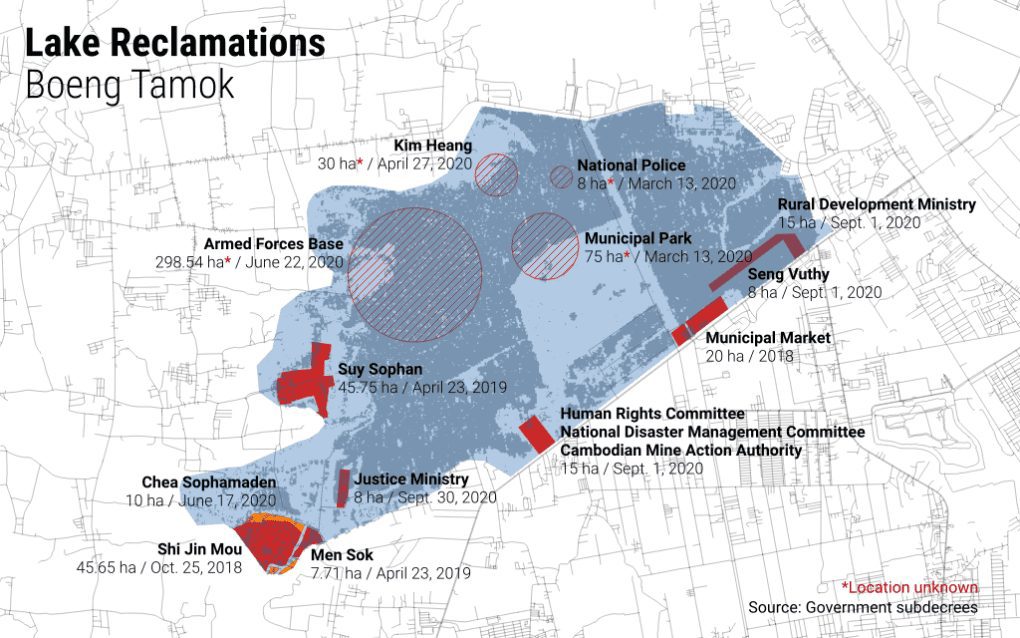

A sub-decree signed by Prime Minister Hun Sen granted 10.5 hectares of the lake to Chea Sophamaden, adding to a series of directives this year that have allocated more than 500 hectares of the 3,200-hectare lake to be filled in for the military, government institutions and private individuals.

Sophamaden has registered her address with the Commerce Ministry at Sophara’s sprawling Toul Kork estate on Street 598, which neighbors call “Chea Sophara Street.” She is married to Yim Leang, a military general and deputy commissioner of the National Police. Leang and the couple’s daughter Yim Beauramey have variously posted about the marriage and family relations, as well as family photos with Sophara, on Facebook.

The in-law relation between Leang and Sophara was previously reported in 2002 in the Cambodia Daily, which noted Leang’s promotion to brigadier-general at the age of 29, making him the youngest general in the military at the time.

Leang is the son of Yim Chhay Ly, a deputy prime minister and chairman of the Council for Agriculture and Rural Development; and brother of Yim Chhay Lin, the wife of Hun Sen’s youngest son Hun Many, according to several previous reports.

Beauramey is co-director of the Park Development in Chbar Ampov with Sophamaden, and has also registered her business address at Sophara’s estate.

Other allocations of lake land in Phnom Penh have gone to the ruling family, including for Orkide Villa on Chroy Changva’s Boeng Kham Porng, a development chaired by Hun Sen’s daughter Hun Mana.

A man who answered a known phone number for Sophara denied he was the land management minister, Leang said it was a matter for the Land Management Ministry, and ministry spokesperson Seng Lot said he was too busy to comment. An email sent to Sophamaden was not answered. Government spokesperson Phay Siphan did not answer his phone. Guards at Sophara’s estate declined to let reporters request an interview.

On Wednesday, in the southwest corner of Boeng Tamok where Sophamaden and two others have received plots, fishermen cast nets within sight of several parked dump trucks.

Koam Nang, a fisherman in his 50s, says the lake is how he and neighbors get food and make money to send their children to school.

“I hate it when I come to fish and see all the trucks,” Nang says. He is worried that soon there will be no lake, no fish and no livelihood.

“We don’t know what they’re doing. We just know that they’re filling up the lake,” he says. “The development is good for the developers. They’re happy with it. But people have nothing to eat.”

Fisherman Nhik Phengvireak, 32, says the area has flooded for the first time in memory since the landfilling started.

“It’s putting a lot of people in a difficult situation,” Phengvireak says. “This year they’re really in the full swing of filling up the lake.”

Asked about the land being granted to the family of government officials, Phengvireak says “it’s hard to talk about.”

“I’m speechless. Because it’s public, and they privatize it so it belongs to themselves.”

All along the southern side of the lake, trucks endlessly carried dirt to several plots on Wednesday. Large tracts of land are emerging from the water, and a dirt causeway now splits the lake in two.

Khun Chamnan, 28, says he was evicted from his lakeside shack alongside about 20 families a month ago.

About 30 district security guards and police and military police officers came during the morning with chainsaws to demolish their dwellings, he says. Some in the area were out fishing, and returned to see their property destroyed.

“We begged them not to do it but they still did it,” Chamnan says. His mother has lived around the lake since the 1980s, he says, and he moved there with his young wife about five years ago to fish.

Now he has three young children, the youngest of whom is just over 1 year old.

“My boy will never know there was a lake here,” he says. “And they may never know about water lilies.”

“We can’t do anything. They just come here to hurt the poor,” Chamnan says.

He has considered taking his case to human rights groups or somehow resisting. “I really want to make an appeal, but I’m scared,” he says. “I’m angry but I’m scared.”

Chamnan says he has received no compensation. “Do you think they would give us land? No way,” he says. “I don’t need money, just don’t evict us. … Even 4 square meters is enough.”

He and his wife still return to the area they previously lived to sell fish. It is also close to their children’s school. They’ve moved to another spot around the lake, but the water level is high and it floods, he says.

“We’ve heard they’re granting plot after plot of land,” he says. “It’s such an injustice to come and take land from the poor to give to the rich. … I’m very angry but there’s nothing we can do, because everything belongs to them. We have no recourse.”

“He’s making people hate him more and more,” Chamnan adds, without specifying to whom he is referring.