In scorching afternoon sun outside the Battambang Court of Appeal last year, 22-year-old Cambodian rapper Kea Sokun declared he had no regrets about the lyrics that led to his 10-monthlong incarceration.

“I’m not sorry,” he told VOD, before guards told him to stop talking.

An independent rapper producing music from his bedroom, Sokun had released rap songs that, while laden in nationalism, attempted to draw attention to corruption and economic inequity. He made international headlines after his arrest in September 2020 due to the viral song “Khmer Land,” which touched on the sensitive subject of Cambodia’s borders. Refusing to apologize for his lyrics, Sokun accepted a one-year jail sentence. (A collaborator who recanted was released from custody.)

Unaffiliated with any major label, Sokun emerged separate but parallel to the rebirth of an original Cambodian music industry led by Khmer-American pop star Laura Mam’s Baramey Productions, founded in 2016, and rap collective KlapYaHandz, which began in the early 2000s. (Both companies declined to speak with VOD for this article).

Following the loss of 90% of Cambodian artists due to the Khmer Rouge and decades of instability, Cambodia’s music industry at first confined itself to cranking out karaoke knock-offs of foreign songs. Then, new production companies fought to invest in Cambodian creative visions to make spaces for successful artists, innovate upon Cambodia’s rich music history, and share Khmer culture on a global stage.

With Cambodian rappers like Baramey’s VannDa gaining tens of millions of views on YouTube, Cambodian rap commands more cultural capital than ever.

“Why have hip-hop and rap been embraced in Cambodia and among the Cambodian subculture abroad, rather than other genres, like country and western?” writes Cambodian academic Linda Saphan. “Cambodian youth in Cambodia and in the diaspora communities feel a discontinuity with the past. They are experiencing economic disparity, social marginalization, and alienation from their history — commonalities with the African American urban counterculture that gave rise to hip-hop and rap. The social message was at the heart of the birth of rap music.”

Cambodian rappers most committed to this ethos, like Sokun, have the least support and face the greatest risks. Despite rap’s popularity, Cambodia-based artists forging the genre’s identity often avoid even indirect social justice-oriented statements in their lyrics — what’s known as “conscious” rap.

“I would love to have the songs be more conscious,” one prominent Cambodia-based music producer said, speaking anonymously due to fears of political blowback. “The younger generation is really aware of the power they have in their lyrics and their raps — they have the attention of the kids.”

That’s not to say the rap being produced is not entertaining and meaningful — at its best, commercially successful rappers share messages of chasing dreams and embracing Khmer identity. But the songs, however powerful, have typically been restricted to personal empowerment and positivity.

“We’re talking about a young music scene that’s still trying to find its voice,” says Cathy Schlund-Vials, a Cambodian-American professor at University of Connecticut who researches Cambodian rap. “Because they want to form a scene and they want it to be nationally legible, but you can’t really do that if you work exclusively at cross purposes with the government. Nothing happens in a vacuum.”

The price of building this mainstream Cambodian rap scene — and the contemporary music industry more broadly — is the absence of social justice commentary in most songs, arguably putting the genre at odds with its roots and one of its potential greatest strengths.

Rap music emerged from Black, urban American block parties in the 1970s. MCs embodied the defiant creativity, joy and rage of marginalized communities under siege from the violence of structural racism and white supremacy. In the decades since, rap has been uniquely positioned as the genre of choice to chronicle the global struggles of the oppressed, inspiring change from the Arab Spring revolutions to the homegrown soundtrack for Thailand’s pro-democracy movement.

The stakes of speaking to social issues are high and potentially deadly in Cambodia, where more than 150 individuals have been imprisoned since 2019 on incitement and related charges for offenses ranging from social media satire about Covid policies to quoting a snippet of the prime minister’s speech in a news article. Yet opportunities may still exist for expressing socially conscious rap, lying somewhere on the spectrum between Kea Sokun’s “I’m opposed to the dictator” and VannDa’s “I heard your b— she wants my d—.”

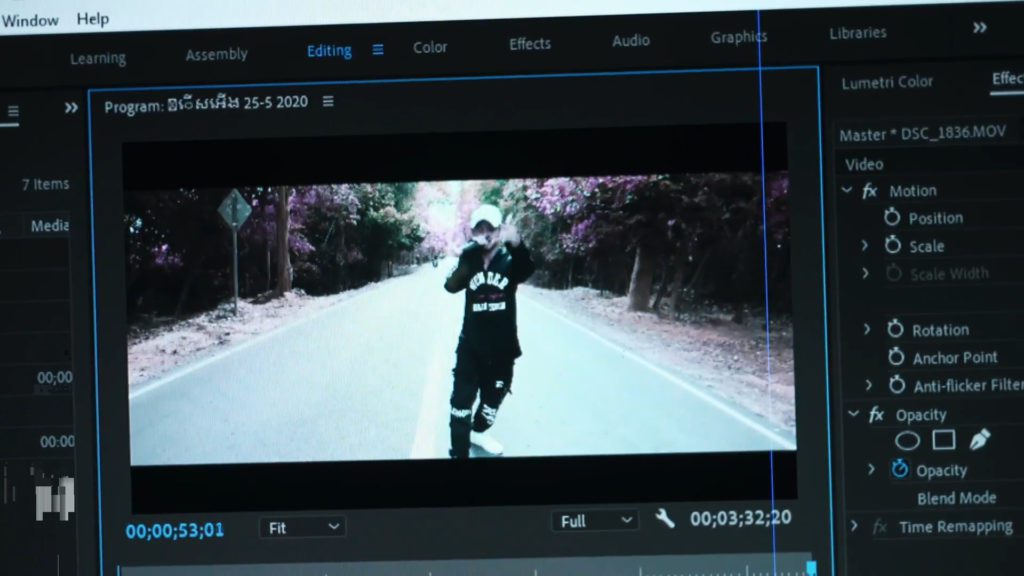

Much of the Cambodian music speaking truth to power emerged from a tight-knit rap community in Siem Reap, unaffiliated with commercial labels. Many of the rappers, like Sokun, first met in the wedding videography business where they gained editing and multimedia skills, sharing an interest in documenting the “truth” about society, set to catchy beats.

The Siem Reap underground rap scene was tired of the romantic songs dominating Cambodian music and felt rap could bring something more raw. As rapper Dmey Cambo declared in his song, “This Society”: “I speak what I want to speak, I speak what I see.”

Dmey Cambo employed the images of slain activists like Chut Wutty and Kem Ley in his song cover art and his lyrics carried more than a whiff of insubordination: “When powerful people fart, the rich stay and smell.” His songs, like Sokun’s, have earned him millions of views and hundreds of thousands of YouTube subscribers.

Siem Reap’s rappers recorded in several dozen underground “home studio” operations developed across the city. It was not hard to make music, and a mic, computer and a quiet space were all that stood between a musician and the potential for social media-fueled fame. Without much guidance, some rappers like Sokun relied on racial stereotypes and the nationalist rhetoric ubiquitous on Cambodian social media to express their grievances with the status quo, warping their messages.

The rappers’ autonomy also came with the responsibility of knowing how to navigate restrictions on expression, where the wrong lyrics could get them in trouble with authorities.

“I feel very, very pressured,” said one Siem Reap rap producer in the aftermath of Sokun’s arrest, requesting anonymity due to fears for their own safety. “They were attacking one to threaten 10. It broke our spirit.”

While this producer had gained hundreds of thousands of views on raps he produced on YouTube, the producer and their collaborators frequently engage in self-censorship, removing “anything that hits or criticizes” from the lyrics.

Brak Sophanna, an established Siem Reap producer, was frank about the tradeoffs he makes in writing socially conscious lyrics due to the fear of facing reprisal from authorities.

“We need to restrict our words,” he said. “I have many songs that I want to release.” He has kept some of them to himself because he isn’t sure how they will be received in the current political climate.

Several years before Sokun’s arrest, police visited the home of the outspoken Dmey Cambo in response to his efforts to “speak what I want to speak.” He later told the Phnom Penh Post: “I will stop composing such songs and turn to write sentimental songs that encourage the younger generation to love and unite in solidarity with one another.”

Rap arrived in Cambodia in the late 90s, ushered in by PraCh Ly, the son of Cambodian refugees in the Khmer enclave of Long Beach, California. A visiting Cambodian DJ got a hold of Ly’s mixtape Dalama — produced on his parents’ old karaoke machine — and brought it back to Cambodia.

Ly’s songs recorded the traumas of the Khmer Rouge regime, breaking taboos and documenting collective Cambodia memory. The Cambodian government attempted to censor the songs by fining radio stations. Still, the music spread.

“If you don’t address something, if you don’t talk about it, you can’t solve it,” Ly said. “For me as an artist, I choose to speak clearly and freely. You know, I’m not giving subliminal messages. If I don’t like what the government is doing, I will likely say it. But I’m not there in Cambodia.”

The notion of confrontational, hard-hitting rap is embedded in the Western, liberal mindset, said ethnomusicologist Jeff Dyer. “It comes out of this framing of liberalism that says, ‘You are your voice, and you only are a person if you can speak truth to power.’”

Cambodia-based singers like rapper DJ Khla embraced this ethos, aligning themselves with the political opposition, and were ultimately forced into exile and obscurity after facing death threats and arrest. Speaking directly against government policies is not a realistic or fair expectation for artists, Dyer argued.

“Do you support somebody who maybe you want to support and get yourself in trouble?” Dyer said. “Or do you let him get run over by the bus and jump out of the way? That’s an impossible ethical question to answer. [Cambodians] have to live with that daily.”

Without getting political, independent rappers have written songs in the perspectives of the most marginalized Cambodians, as in Dmey Cambo’s recent ode to migrant workers, vividly describing the protagonists’ challenges without delving too deeply into their root causes. In another song, rapper Morno narrates the true story of a high profile manslaughter case in which the daughter of a wealthy family ran over a university student. The perpetrator’s family paid the victim’s family to drop the legal charges.

There are less explicit ways in which Cambodian artists positively impact society, Dyer, the ethnomusicologist, explained. For example, recognizing elders and paying homage to past generations, especially when those traditions were nearly eradicated by the Khmer Rouge. Contemporary art performances have reimagined traditional stories with powerful visions of social justice.

Dyer also points to Khmer1Jivit — an outspoken Cambodian rapper who relocated to Texas — and his song “Unforgettable,” dedicated to Kong Bunchhoeun, a famous songwriter and poet turned political exile.

“This could be seen as a subversive political statement, giving homage to somebody who has had issues with the government in the past,” Dyer said.

Cambodian rap has explicitly confronted rigid cultural norms in its messaging. Khmer Rap Boyz proclaimed short hair’s sexiness at a time when long-hair was the norm for women. The very presence of female rappers like Klapyahandz’s Lisha performing on the mic challenged the submissive attitude enshrined in Cambodia’s traditional Chbab Srey code of conduct for women.

Rather than speak bluntly about potentially negative social issues, rappers and other artists in Cambodian need to “layer their expression” and avoid being so direct in their meaning, said performance artist Sareth Svay, co-founder of the Phare Ponleu Selapak art school, which includes the Phare circus.

“That way you can continue to speak out to improve your work and keep your voice,” he said.

In his music video for the song Khmer Blood, VannDa performs in the threatened forests of the Cardamom mountains. Cambodia has one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world, and VannDa also released a short documentary discussing the national park with a ranger.

Yet Cambodia’s most famous singers and the record labels supporting them have usually been tied to power and almost always kept within its politics. Hanuman beer now appears frequently in VannDa’s songs; Hanuman’s chairwoman owned a logging company allegedly linked to the murder of environmentalist Chut Wutty.

Cambodian legend Sinn Sisamouth performed propaganda songs for the oppressive Lon Nol government during Cambodia’s civil war. Decades later, beloved pop star G Devith shimmied alongside military and police officers to the refrain of “let’s dance together / eat rice with chicken / and come dance with me.”

Much of Baramey Productions’ success and reach has been due to the support of sponsors like Cellcard, owned by an oknha in Prime Minister Hun Sen’s inner circle.

The tension between artistic freedom and the need to maintain an apolitical stance to access resources and a platform is not unique to Cambodia, playing out dramatically in the American music industry during the civil rights movement throughout the 1950s and 60s. Black singers faced intense pressure from studio executives to keep social commentary out of their music and were warned it would destroy their careers, said hip hop historian Jeffrey Ogbar. Of course, free speech safeguards in America offered protection from worse consequences, he noted.

Some artists under the most famous Black-owned label Motown refused to comply, leveraging their stardom to push through social commentary. Drawing on all his influence, Marvin Gaye managed to publish the pro-civil rights 1971 album “What’s Going On,” now hailed as one of the greatest musical works of the 20th century.

In a 2018 speech available online, Baramey Productions CEO Laura Mam explained how she went from a UC Berkeley anthropology graduate to accidental Cambodian pop star. After moving to Cambodia, she turned down a studio career producing Khmer covers of foreign songs to create her own production company, seeking the independence of socially conscious singers like Lauryn Hill.

Mam acknowledged much of the new Cambodian music then from Baramey focused on romance, arguing love was the primary concern for the country’s post-conflict baby boomer generation, where the majority of the population is under 35.

She compared Cambodia to post-World War II U.S., when after a period of national regrouping the revolutionary 1960s arrived. Musicians from the era “got everyone to start thinking even bigger,” Mam said. The woman at the forefront of Cambodian contemporary music is excited because “we have an original music movement starting to speak beyond things we talk about every single day.”

If Cambodian rap is already celebrated for songs like VannDa’s “Time to Rise,” incorporating Cambodian traditional instruments, melodies and language to international acclaim, Mam also implies the industry will reach its highest potential after its music can reflect the fullest range of Cambodian experiences, struggles and aspirations.

When the conditions for this artistic landscape will arrive in Cambodia is at least partially in the hands of the labels, artists and their audiences. But the current limits are not their fault.

For now, unlikely to get signed by any music label, Sokun, the formerly incarcerated rapper, for a time worked at a labor rights NGO and now said he plans to continue writing songs he believes in.

“I would like to say that my aim is to educate,” Sokun said. “I always want to use songs as mirrors to reflect the reality in society. I just want to speak the truth.”

Additional reporting by Mech Dara and Mech Choulay