Indigenous communities attempting to register communal lands are often left in bureaucratic limbo and are at risk of losing this land, advocates said this week, even as the government handed more than 4,000 hectares to three communities in May.

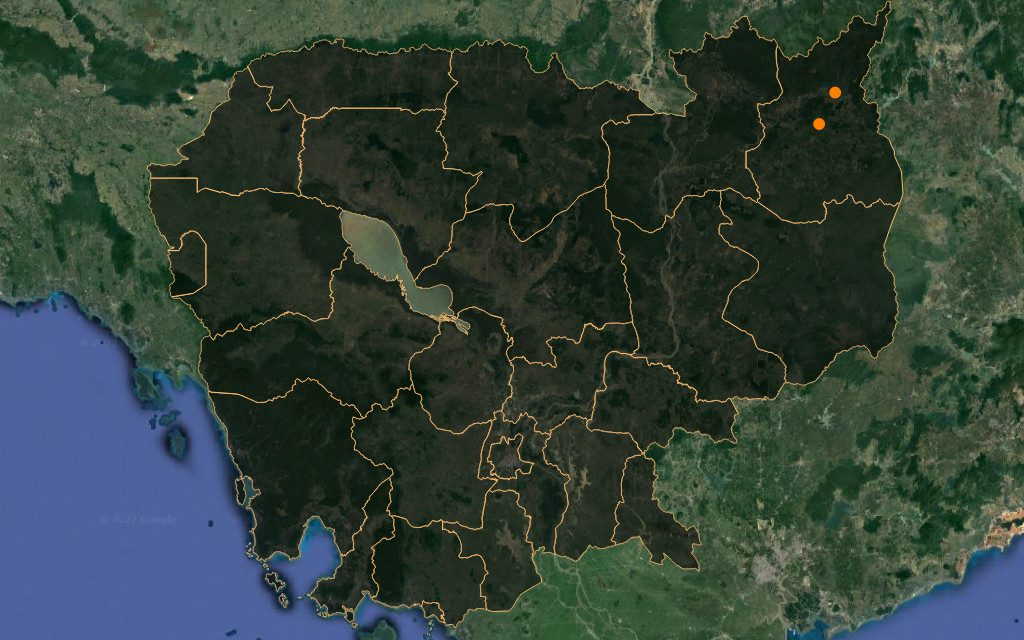

Three sub-decrees from May, but released by the government late last week, gave close to 4,000 hectares of land to three separate indigenous communities in Ratanakiri province, completing the arduous communal land titling process for residents.

Indigenous advocates and other communities VOD spoke to said applications were routinely stuck in administrative roadblocks, often leaving these land vulnerable to clearings and capture.

The Cambodia Indigenous People’s Organization said latest data showed that only 37 out of 500 communities nationwide had received titles. Previously, as of 2019, NGO Forum estimated that 24 of an estimated 455 communities had received land titles.

Yun Mane, director of the Indigenous People’s Organization, said the registration process was costly, complicated and laden with a lot of paperwork.

“If the community had to do it themselves, they couldn’t do it,” she said.

Documents were required from three different ministries involved — interior, rural development and land management — and was a time consuming process for many communities.

On top of the red tape, communities were dealing with land disputes that were chipping away at their lands, compounding the issue with a slow registration process.

“The community requests the land now because it is not for only the current residents, but for their children in the future,” she added.

While most Cambodians place high value on their farmland, indigenous groups say communal lands are integral to their ways of life. They use the land as burial grounds, for rotation farming and to harvest forest products.

Rev Tren heads a Kreung community of 146 families in Ratanakiri’s O’Chum district. In 2008, the community found out that a company was scouting the area to mine for iron or precious gems.

The community was startled and immediately worked on an application for a communal title, submitting it in 2008. Seven years later, they were given a title and the company never returned.

“If we don’t collectively manage it, we were worried that the outsiders or private companies would abuse it or search for this and that,” he said.

The official recognition of their lands also helped preserve their traditions as burial grounds and spirit forests remained, Tren said. They could also use parts to plant rubber, cashew and other forestry products.

Others are hoping for similar luck, but without waiting so long. Kham Leangpak is the head of a Kreung community in Taveng Loeu commune in Ratanakiri — the same area where two of the three new communal titles were announced this week.

The community has around 150 families and are still awaiting a communal title. They applied for it in 2021 and were told they will get it at the latest in 2023.

“If we don’t have a hard title, we don’t have the right to claim [the land],” he said.

The quick turnaround that Leangpak expects was not the case for another Kreung community in La’ak commune. The community is one of the three that received a title in May and will now be in control of 1,217 hectares of communal lands.

Veng Bun Mong is the head of the community and said they started the application process in 2009, made final submission in 2013 and a decade later they received the communal land title.

“We had community meetings very often and had a limited budget,” he said. “I have been waiting for this since I was in my 30s and now I’m in my 40s.”