The government will take nearly 1 million hectares out of protected areas across the country to create “community zones” with land titles, but the exact locations of these areas — and who will get titled land — are still unclear.

A total 933,577 hectares inside protected areas across the country will be designated as community zones with “the possibility of issuing land titles,” according to a Council of Ministers document signed on November 30.

Another document, signed by Kaen Satha, a Council of Ministers secretary of state, tasks the Environment Ministry with identifying communities residing in the zones that could qualify for receiving land titles.

The document also orders the Environment Ministry to further study core areas in the protected area and “adjust” the area boundaries, adding that the ministry can “take possession of land that has been occupied but has not been used for development or any investment area whose contract has been terminated in a protected area to retain control and register it as state property,” according to an unofficial translation seen by reporters.

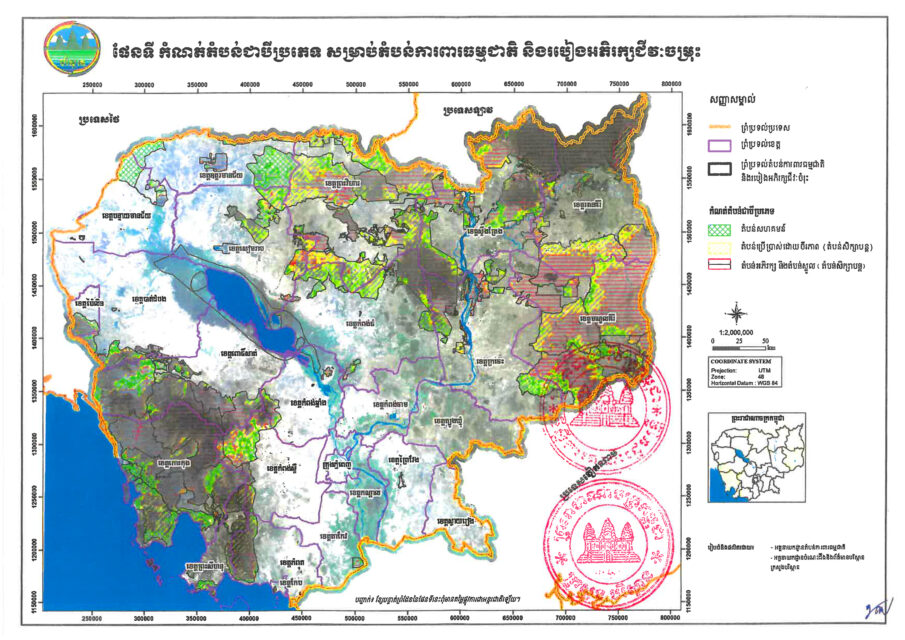

The document came with a map of protected areas across the country, marking the proposed community zones in green, but the exact coordinates nor areas of these zones were not included.

The map also includes core conservation areas, marked in red, and areas in yellow that are still being studied by the Environment Ministry.

Environment Ministry spokesman Neth Pheaktra said the decision to mark 933,577 hectares as community zones conformed to the Protected Area Law, and was part of zoning protected areas into core conservation areas and community and sustainable-use portions.

Community zones manage the “socio-economic development of the local communities and indigenous ethnic minorities and contain existing residential lands, paddy field and field garden or swidden,” Pheaktra said. “The decision [is based] on the law and interests of people and for also social harmonisation.”

Based on what can be seen in the map, some protected areas stand to lose extensive areas: Boeng Per Wildlife Sanctuary, mainly in Kampong Thom, will have patches of community areas through the center and all sides, and all of the Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary area in Oddar Meanchey and Siem Reap appears to be turning into a community zone.

The map shows community zones across much of Koh Kong’s Botum Sakor National Park that hasn’t already been distributed to the Union Development Group, and the southern half of Phnom Oral Wildlife Sanctuary in Kampong Speu is also marked for communities.

The Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary, which spans Preah Vihear, Koh Thom, Kratie and Stung Treng, has its northern areas mostly covered in yellow areas under study, while sections of the eastern and southern borders are marked for community zones.

Mondulkiri’s Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary also has community areas covering its southwest and eastern borders.

Wildlife Conservation Society Cambodia, which is managing the sanctuary and a carbon offset project that needs its trees, said the mapping seems to align with the zoning that’s already been drafted for Keo Seima, but the map was not clear enough to know for sure.

Cambodia’s protected areas are supposed to be zoned based on the level of protection needed: Core conservation areas hold the highest penalty for encroachment, while people can live and work in “community and sustainable use zones,” the group said in an email.

It said clear zoning will make it easier to protect ecosystems under the law, but noted that WCS had not yet received coordinates of the community zones outlined in the sub-decree.

With zones clearly marked, the group predicted that indigenous groups might have an easier time attempting to gain communal land titles within the community zones, while authorities would have a better chance at preventing new migrants to the area from clearing community use zones.

“It will be important for Cambodia’s protected area network to ensure the high level of legal protection provided to Core and Conservation Zones is respected, whilst ensuring Community and Sustainable Use Zones benefit local communities currently within these areas, with controls to prevent land grabbing,” it said.

Community protected areas and WCS’s livelihood protection projects would help encourage residents to respect core conservation areas, “[a]lthough the new Community Zone does allow conversion to private ownership and with it an increased risk of deforestation,” it said.

“Competing interests” will likely arise as the government attempts to issue titles, said Courtney Work, an associate professor at National Chengchi University who has extensively studied Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary, as well as the indigenous communities that reside there and industrial logging operations that vie for its timber.

Work said it’s too early to tell if the people that have long lived in and used the forest for their livelihoods and spirituality will benefit from the plan to give out titles.

“I suspect that the real scramble will be between large, well-connected private land grabbers, local residents, and migrants. Indigenous collectives are putting forward calls for communal title, it’s hard to tell what that will bring,” she said.

However, Work predicted that the indigenous and long-staying communities will not be the beneficiaries, and instead the titles will be granted to those who encroached and cleared protected land.

“By making the existing encroachment legal and relaxing the restrictions at the periphery, it will increase the pressure on the core,” she said.

Correction (December 26): An earlier version of this article misstated that Kaen Satha was a a deputy prime minister. He is a secretary of state, and issued the letter for the office of the deputy prime minister in charge of the Council of Ministers.