Some 1,333 families in Koh Kong are being offered 1 to 3.5 hectares each over a decade-old land dispute with the Union Development Group, as some families say they reject the deal and will fight to stay on their old land.

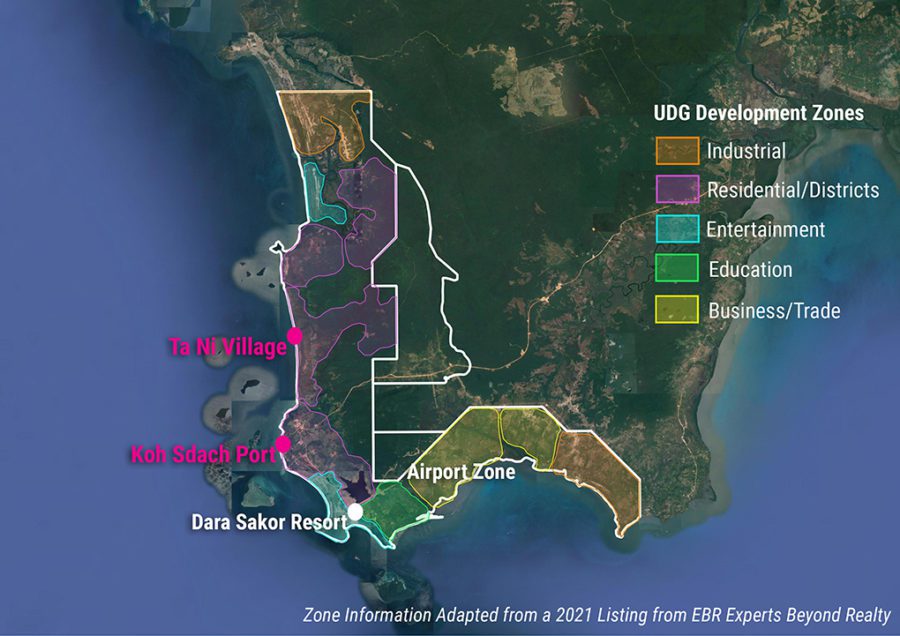

The U.S. has sanctioned UDG, a massive development that includes an airport and long stretches of coast, over accusations that the company burned down villagers’ homes and over suggestions of the project’s links to the Chinese military.

This week, the Koh Kong provincial administration issued an announcement about the latest compensation process in Botum Sakor and Kiri Sakor districts, saying residents were placed in three categories: 247 families living on company land, 255 families living on protected areas or otherwise in the “wrong” location, and 831 other families requesting compensation.

The announcement said the majority of families had already agreed to compensation, and a lottery to distribute land plots would be held on Friday.

Hour In, rights group Licadho’s provincial coordinator, said the first group was set to receive 3.5 hectares and $9,000, the second group 2 hectares, and the third group 1 hectare. The third group was made up of families who had previously received some compensation, In said.

But people would find it hard to accept the fixed plot sizes on offer through the broad categorizations, In said, suggesting that authorities should give compensation based on the actual land sizes currently held by residents.

“If the settlement categorizes people who live on the location and outside the base, the settlement process won’t end,” In said. “And with allegations that they live on [protected] park land and saying they are in the wrong village, commune or district, the solution between the people and company cannot be reached.”

Koh Kong deputy governor and spokesperson Sok Sothy, who was linked to police questioning of a local journalist earlier this week, could not be reached on Wednesday.

Saing Puy, a resident of Kiri Sakor district’s Koh Sdech commune, said her family farmed 8 hectares full of fruit trees, and her mother owned a further 12 hectares. She was only offered 2 hectares.

“I am not satisfied with such a solution. I have been asked many times to deal with the actual size of the land, the situation, the geography and the occupation. But the result is that my family cannot accept this again. And for this solution there was no meeting or discussion with the people directly affected. He showed up to announce it without even showing the land [being offered] in exchange.”

Sem Thy, a resident of Kiri Sakor’s Prek Khsach commune, said he also had about 8 hectares. The new settlement announcement was about pressuring people to accept compensation, he said.

“For me, I will not leave. I’m committed to fighting to the death to live there, even if everyone has left. Because this solution is not appropriate. I cannot accept this exchange,” Thy said.

The UDG development was granted 45,000 hectares of land in 2008 and 2011, and past research reports have said more than 1,000 families were forced off about 10,000 hectares, and 1,500 houses dismantled and cleared. A visit to the coast in June found villagers defending their houses against demolition by company security.

Preap Ratha, another resident of Prek Khsach, who claims about 0.6 hectares, said she also refused to leave. She feared hardship and the loss of her livelihood after seeing that some people who left her village after accepting compensation faced difficulties at resettlement sites.

“They were given 2 hectares of land and some money, and [the company] made the house for them to stay, but they still came to do business in the old place and their living is very bad,” Ratha said. “Where I am, I can do business by land or sea. For food, if I do not have money, I also can find delicious food to eat because I can find it myself. But in the new place where could I go? It is on a mountain. Where is the water where we can find fish, and the sea where we can find crabs and snails?”