Murders, kidnappings, corpses on the beach — news reports out of Sihanoukville paint a picture of violent and serious crime in the coastal city. But authorities are increasingly shutting down information about police work and pressuring journalists over negative stories, crime reporters say.

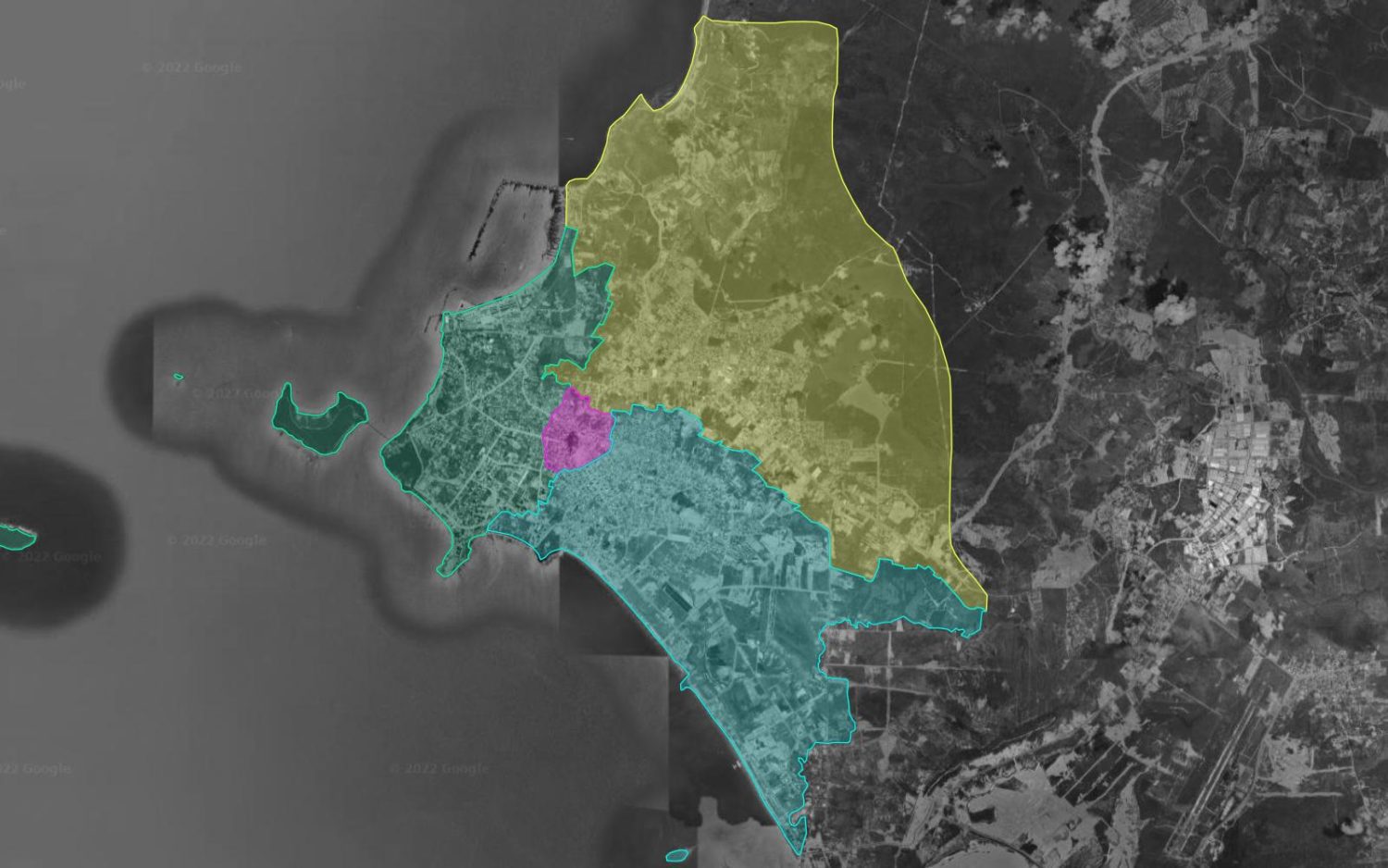

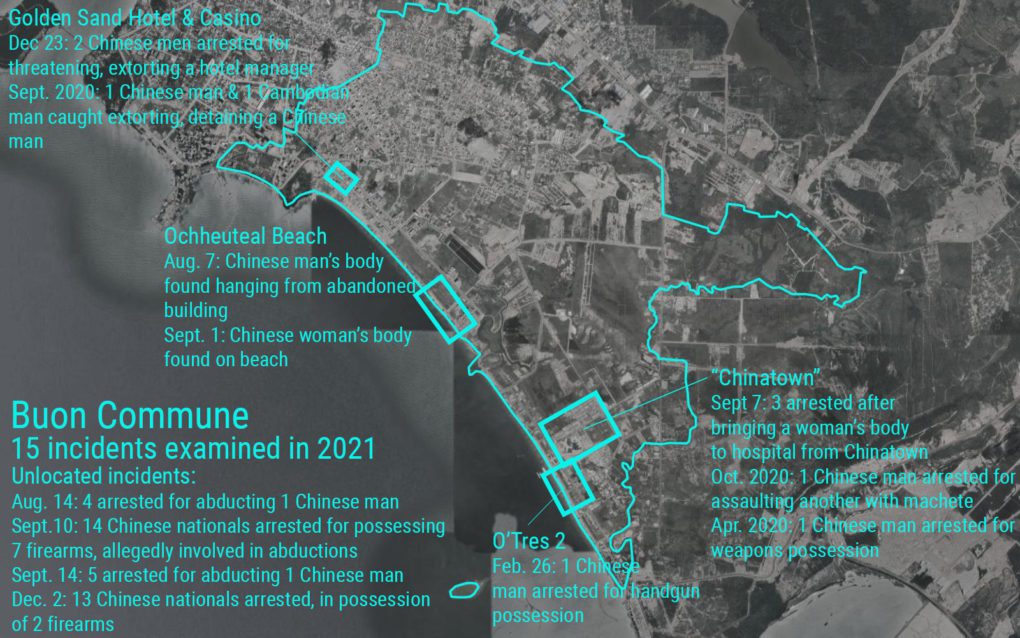

A sampling of local crime reports emerging from the city over the past two years include at least six reported cases of bodies found either in public locations or washed up along the beach; 19 homicides, assaults or firearms cases; 11 cases of extortion and detention; and some other serious crimes.

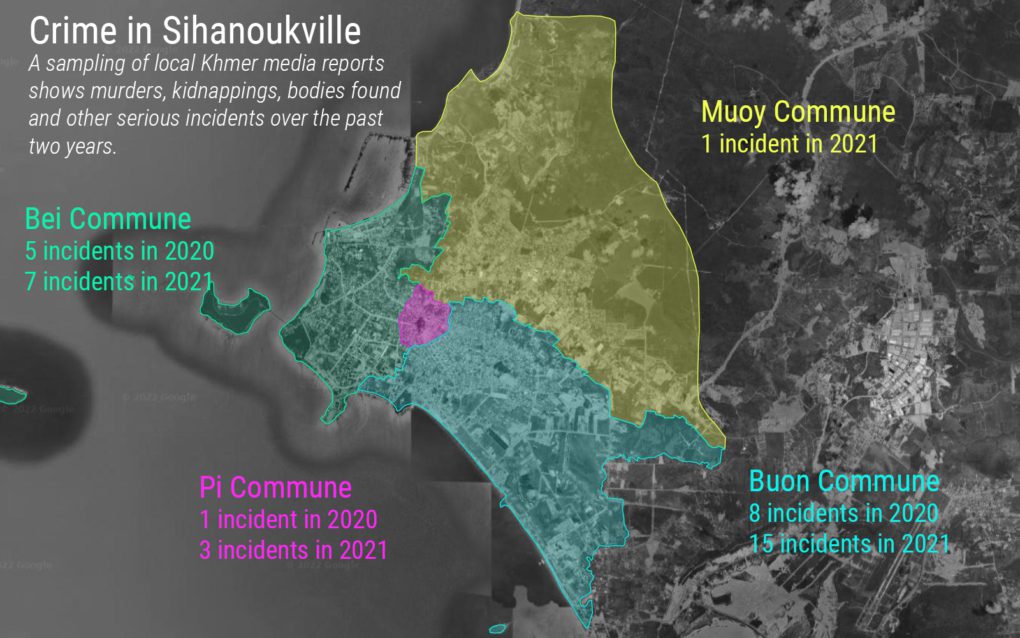

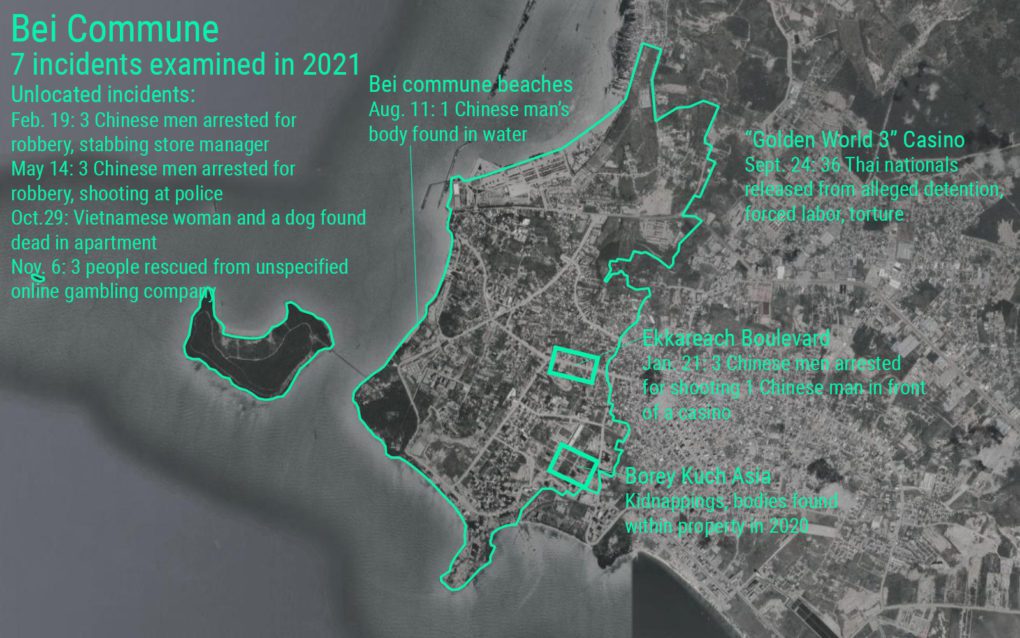

VOD reviewed 14 cases in 2020 and 26 cases in 2021, and more than half of these cases were clustered in Sihanoukville’s Buon commune. Many happened at common locations: along O’Tres and O’Chheuteal beaches; a borey called Pearl of Asia in Bei commune; a compound called “Ksach Meas,” or Golden Sand, in Buon commune; and the same commune’s notorious “Chinatown” complex.

The majority of cases counted Chinese nationals as victims. Among the only cases that didn’t involve Chinese nationals as victims were a report on 36 Thai nationals rescued from Bei commune’s Golden World 3 casino in September, a November rescue of three victims of unspecified nationality, and a woman found dead with her dog in October. The woman was initially thought to be Chinese before being identified as Vietnamese.

The crimes covered by Cambodian media — predominantly Phnom Penh-based news outlets ranging from Post News and Khmer Breaking News to the government-aligned Fresh News — mostly stemmed from police response to crime.

Cambodian reporters in Sihanoukville suggest that the crimes that make the news are nowhere near an exhaustive list, as local reporters are often barred by authorities from getting information about crimes that they hear about. A Chinese journalist also told VOD that he hears about more crimes than he can possibly cover, and faces other obstacles to gathering information — and sometimes threats.

Covering Crimes Against Chinese Nationals

Huang Yan, a journalist with a Chinese-language news site, said he’s constantly covering kidnappings, deaths and other crimes committed by and against Chinese nationals in Sihanoukville.

Crime reports tend to increase ahead of the Lunar New Year globally, but he told VOD in late January that he heard of seven different crimes in Sihanoukville a week before the holiday, including two handcuffed bodies found in a grave, two people falling from buildings, and two women found dead in two different cars under suspicious circumstances.

Yan said he had heard from a man in China who had received a call from local police saying his father had died in Cambodia, but when the man asked Yan for information, he didn’t have sufficient details about recent victims. “Right now I don’t know which case is connected to his father.”

He said he hears about more crime on social media and from sources in the city than he’s able to report because it’s difficult to verify the details. Yan cited one case from January, where a man fell from a building of an online company but the boss “already controlled it” before reporters or Sihanoukville police could cover the case.

“I can’t report it, because I cannot confirm what happens in this case, and if I cannot confirm, I cannot report it as true, [because] it’s not 100 percent that it’s true,” he said.

Having covered Cambodia for Chinese expatriates and readers in mainland for three years, Yan said there was a similar spate of crime in 2019, as online gambling proliferated in Sihanoukville before the ban starting in January 2020 and then the Covid-19 pandemic and global freeze that followed.

Beatings and alleged homicides were common, but Yan said he also noticed more crimes like gunshots to the sky at that time.

“Before they were very open, because online gambling was legal in Cambodia, this was a [known] industry for Sihanoukville before 2019 … and they could talk about it, it was legal. Before they banned online gaming, it seemed like the gaming could last there in Cambodia forever, and they had buildings in the city town center.”

Yan observed that online gambling and scam operations turned secretive after the ban, but Covid-19 travel restrictions made it harder to recruit and bring Chinese speakers into this industry, leading to the rise in abductions, with kidnapped individuals reportedly being sold for more than $10,000, sometimes multiple times.

The journalist said he’s occasionally threatened over his reports. On one occasion last year, he reported a crime at an online gambling company based in Phnom Penh. The company contacted him at first to take the article down and he declined, but he removed the article after Cambodian police allegedly threatened him in a phone call one week later.

“[They said] we have orders to arrest you, but if you delete the article, nothing will happen, but if you don’t delete I will arrest you,” recalled Yan, adding that he rarely deletes stories.

Threats in Khmer

Though Chinese language media are filled with reports of crimes against Chinese nationals, Sihanoukville-based news outlets in Khmer have not covered crimes in Sihanoukville as extensively. Two Cambodian journalists based in the coastal city, who spoke under pseudonyms out of fear of threat and intimidation from authorities, said they were aware of the rise in crime but afraid to report on it.

Hong Reaksmey*, a Sihanoukville journalist, said there were more than 50 media outlets in the province, and while many of the journalists hear about crimes, they don’t report on them. He said they either fail to get information from authorities or feel pressure not to portray Sihanoukville in a negative light.

When Reaksmey calls authorities to ask about a crime he’s trying to verify, they often will pretend not to know about it.

“They are hiding almost every crime, especially most of the serious crimes, but sometimes a journalist knows but they do not have clear sources and they do not dare to write about it,” he said. “Professionally, when we know it but we do not have a clear source, we cannot write about it … without police or sources or general people saying it.”

Heng Sambath*, another journalist, said he only heard about two bodies found handcuffed at two different locations in January through nearby residents, as the police did not say anything about it. He said police sometimes give information to journalists they select.

Both Reaksmey and Sambath said they noticed a change in their access to information after Kuoch Chamroeun became provincial governor, saying the government seems less willing to give interviews and facts to journalists.

“There are restrictions on [journalists] after the new governor had been promoted, and if anyone dares to publish constructive criticism or news about negative impacts, [authorities] will investigate them, so it is very restricted under the current governor’s mandate,” Reaksmey said.

In response to questions about restrictions on journalists covering crime in Preah Sihanouk province, provincial information department director Or Savoeun said, “Where did you get this information?”

He said there was no difference in access to information in the province, before implying that reporters’ inability to do their job may be related to their professional skills.

“The authorities still support and give full rights and freedom to professionals in the media outlets, but from my point of view, it is up to our talents … we must have the capability to perform the skill, and not every job is easy.”

When asked if reporters were receiving too little information from authorities, Savoeun said that officials were very busy, and journalists should understand how busy they were.

Sambath, the journalist, added that he knew some journalists in Sihanoukville who had changed their job because it became too hard to report on the facts without risking trouble.

When asked about the pressure authorities put on journalists, Sambath said he was “speechless.”

“The most important thing is the provincial governor does not provide rights and freedoms for journalists,” he said, adding that they had a much easier time reporting crimes in Sihanoukville under former governor Yun Min.

‘I Don’t Know About It’

Asked about the reported crimes, police officials and village chiefs were reluctant to talk. Buon commune police chief Sam Prak, when asked about the reported discovery of a body in September, said: “I don’t know about it.”

About a more recently discovered, handcuffed body, Prak said police had investigated and found the people involved, but declined to give details.

The commune’s Bei village chief Som Sreng simply said he didn’t know about crimes. Pram Muoy village chief Chea Ring initially denied crimes in his area.

“In my village there are no shootings,” Ring said, while explaining that some people had only tried to escape compounds due to Covid-19.

“In 2020 when they were not allowed to go out due to a lockdown, they jumped and escaped. … This is not a serious crime and it was between Chinese and Chinese people.”

When asked about a handcuffed body being found, he acknowledged a cowherd smelling the corpse as it was not fully buried. It was found about 500 meters from Chinatown, but it wasn’t clear “where he had been killed.”

“There is only one case,” he said, and when asked about three further reports, initially said he didn’t know. But he later acknowledged: “Yes, there are two or three cases of bodies being found here.”

“They were foreign so it’s hard for us to follow up.”

Sihanoukville city police chief Ky Visal said he did not know about the Chinatown body.

Outside the city, Prey Nob district’s O’Oknha Heng commune police chief Chou Maroeun said a body was found there in January this year.

“People were very shocked when they saw the body. … We were also shocked — we have never seen such a case,” Maroeun said, adding that the body appeared to be that of an underage Chinese girl and was bruised.

Scams and Crime

Crimes associated with the online scam industry in Sihanoukville have started to catch international attention, particularly in mainland China, after reports last month of a “blood slave” whose blood was allegedly harvested until doctors struggled to perform a basic blood draw.

However, that man’s case has since been disputed by Cambodian police and the Chinese Embassy, and the alleged victim and a leader of a volunteer team that rescues and houses Chinese nationals from scam compounds had been arrested and questioned. Chen Baorong, the volunteer team leader, had been sent to Sihanoukville with two others for questioning, with a provincial spokesperson saying Tuesday they were preparing to press charges for alleged crimes by Chen.

This week, Thai media reported another alleged case of blood harvesting involving a Thai national who was saved from a slave compound in Cambodia, and was potentially at risk of having their organs harvested.

Yan, the journalist, said that Chinese audiences, particularly people in mainland China, are closely following reports of crimes against Chinese nationals because they’re shocked and scared to hear the details of the crimes happening in Cambodia.

About one year ago, Yan reported the murder of former Tencent executive Xiao Bo in Phnom Penh, with surveillance footage of two men pulling Bo and his girlfriend out of an elevator with arms wrapped around their necks and weapons held at their waists. He said a number of major Chinese language outlets covered this case too, attracted by the entrepreneur’s status and the clear surveillance footage.

At the time, Yan said he tried to follow up with Cambodian police but received little information. At one point local authorities said the two alleged kidnappers were near the Thai border, but he also called Thai police, who said the suspects never crossed into their jurisdiction.

“The CCTV shows clearly what happened, so we wonder why can this happen, for Chinese people they wonder why this happened, so it was a significant event here we reported on,” he said. “The police also said we will try to find the answer but now it’s one year and we don’t know anything that happened.”

*Names changed to protect sources.

This article was updated at 1:30 p.m. to remove information about a source for safety concerns.