November is usually a happy month for Cambodia’s fishermen.

As the rainy season ends, the waters of the Mekong and its many tributaries should provide a bountiful supply of fish to feed their community and sell at market.

But this year, as has become the trend, the nets were less full than the year before.

“We should get a lot of fish this month, November and December, but we get so little fish this year,” said Y Ya, 57, a fisherman whose boat is moored to the shore in the capital city of Phnom Penh.

“Fish are declining every year. I don’t know where they have gone,” he said. “Everyone’s complaining.”

Ya, whose parents too are fishermen, lives with his wife on their 1-meter wide and about 2.5-meter long wooden fishing boat.

He is among more than 60 million people across the region whose livelihoods rely on the Mekong, which flows from its upper reaches in China through Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.

While Ya estimated that his daily catch had plunged by half in just the past year — and even more drastically over the past decade — researchers have also observed disturbances to Mekong water flows due to hydropower dams and climate change that have disrupted fish habitats, breeding grounds, abundance and diversity.

Turbulence

For the past three years, water levels in Cambodian rivers have hit record lows during the wet season, when they should have been rising and creating habitats for fish to breed.

In 2019, a sharp peak in September was surrounded by sudden drops to low levels in the Mekong, Tonle Sap and Tonle Bassac. In 2020 and this year, the rise in water came late, in October, and generally fell short of average, according to data published by the Water Resources Ministry.

Fishermen say they have noticed the river’s height rising and falling quickly.

Scientists like Alan Basist are also seeing changes to the annual cycles, which they link to hydropower dams and climate change.

“The dams hold back a tremendous amount of water during the wet season, because that’s the time that they can fill the reservoirs, and that water no longer flows down and floods the lower basin like it traditionally did, which the fish are attuned to. Instead, that water is released during the dry season to produce electricity,” said Basist, president of Eyes On Earth, a U.S.-based NGO that monitors the flow of Mekong.

“So the fish and the ecology are tuned into a natural rhythm. And what happens when you build dams, dams naturally hold back the water in the wet season. … If that natural pulse of water doesn’t come down, then it affects the whole ecology, the whole movement of fish, the movement of larvae, the breeding. … All of that is tuned to their natural rhythm.”

Brian Eyler, Southeast Asia program director for Stimson Center, an American think tank, has looked closely at Mekong-wide data to show that reservoirs for hydropower dams are likely reducing water flows during the wet seasons and increasing them during the dry, smoothing out the peaks and troughs of the annual cycle.

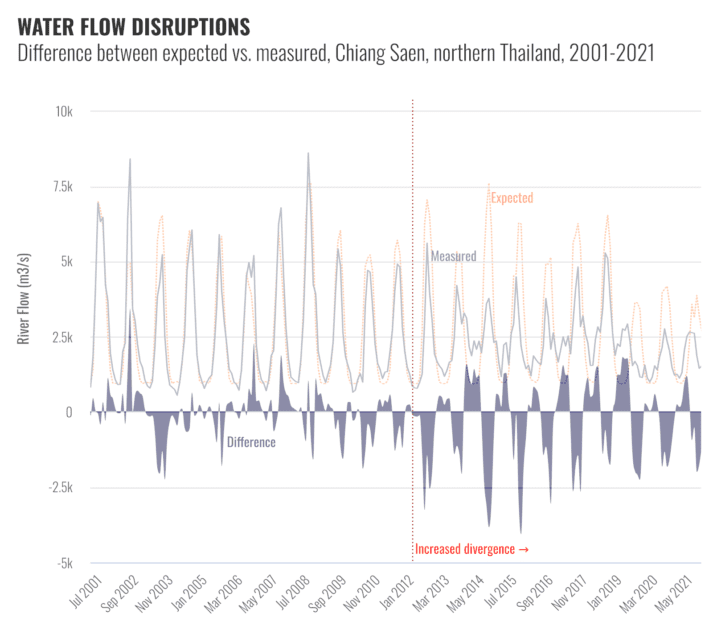

At one monitoring station in northern Thailand, actual and expected water flows diverge significantly starting around 2012. The divergence means something upstream, likely dams, is altering the Mekong’s natural flow, according to Eyler’s Mekong Dam Monitor project.

The hydropower dams take the water out regardless of weather variability, Eyler added.

“So it’s taking the same amount of water out of the system. If the wet season is very wet, if the wet season is very dry, the dam acts the same. So the dam hurts the Mekong more when the Mekong wet season is very dry,” he said.

Habitats

Every November the Mekong river swells with water flows from its upper reaches in China, combined with torrential rain of the region’s wet season, which typically spans June to December.

“The higher the water, the longer the flood stays, the more fish they’re going to get. [Fishermen] know that. They’ve been doing it for decades,” said Eyler.

The total water is more than enough to fill the Mekong and spill into the lower areas around it. The engorged water brings nutrients to land around the basin, and flooded vegetation acts like a coral reef and nurtures a huge abundance of fish. It leaves productive farmland and fish-stocked lakes when it recedes during the drier months. With water comes the fish that provides a food source and income to people who live along the river.

In October, the Mekong River Commission released two reports that looked at the decline of fish and fishing families’ livelihoods in the region.

They found that development along the river and climate change had stressed the Mekong and changed its ecosystem. Those who rely on the water resources are “increasingly under pressure,” the authors found. “Fish abundance and diversity need to be protected to sustain food supplies for millions of people,” they said.

The commission has also separately projected that fish biomass dropped 15 to 40 percent across the Mekong basin, including the Tonle Sap, between 2007 and 2020, with further declines expected into the future.

In 2019, the commission said 10 percent of fish species in the Mekong, out of around 700, were at threat of global extinction. The Siamese flat-barbelled catfish was declared extinct in 2013.

Ya, the Phnom Penh fisherman, said he too had noticed some fish species disappearing. “We are wondering but we don’t know why,” he said. “Perhaps once in a long while you get one of these fish.”

Disruptors

Rapid economic growth in Southeast Asia has caused demand for power to increase 60 percent over the past 15 years, according to the Mekong River Commission.

Between 2005 to 2015 the amount of electricity generated from hydropower in the Lower Mekong Basin jumped from 9.3 GWh to 32.4 GWh — a more than three-fold increase.

The gross value of the power was estimated at more than $2 billion, up from around half a billion a decade ago.

As of 2019, there were 89 hydropower projects in the lower Mekong basin, with 12,289 MW of total installed capacity, and 30 more were in the planning stage capable of producing 30,000 MW, the commission said.

“But those benefits come with potential costs,” the commission said in a statement on its website. The cascade of dams had increased dry season flows and reduced wet season flows and sediments. “The decline of fisheries could cost nearly $23 billion by 2040. The loss of forests, wetlands, and mangroves may cost up to $145 billion.”

The commission called for greater coordination between countries and environmental awareness, “to restore the ecological balance to the River we once knew,” noting population growth as another major disruptor.

Eyler, the Stimson researcher, said dam construction, combined with climate change, was harming the rivers.

“The two work together to destroy the Tonle Sap,” Eyler said. “That’s a big message. We’re gonna start pushing this message out soon.”

Rains from the Pacific were arriving to Vietnam later in the year, producing a cascade of effects in Cambodia.

“Some water comes from China, but a lot of water also comes from Vietnam,” Eyler said. “In fact, during the wet season, most of the water’s coming from Mondulkiri province and Ratanakiri province and, and across the border in Vietnam. That’s one of the wettest parts of the world during the wet season.”

The climate has changed, the river ecology has changed; the flow has changed. These changes hurt the Mekong and the people whose lives depend on it.

Vulnerability

In its Global Climate Risk Index, Germanwatch has ranked Vietnam among the 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change in eight of the past 10 years. Cambodia has also made the top 10 some years. The U.N. says Cambodia has also consistently ranked in the top 10 in the world, and top three in Asia, due to dependence on fishing and the potential for flooding and droughts.

Ya and his family noticed that this year the water rose late September and started to go down at the end of October, another short peak that affected fish numbers. They say the expense on gasoline exceeds the income they get from fishing.

“We only get a lot of fish in the floody season, but this year the water rises so late and goes down too fast,” he said.

A decade ago, the couple would be busy catching a bounty of fish in November, a lucrative season to catch fish — he claimed it was as much as 200 kg per day.

Now they are not sure if they will be able to catch that much over two months of fishing. “Last year we could get from around 20 to 30 kg per day. Now we get about 5 to 10 kg per day,” the fisherman said.

Ya’s wife, Ren Ny, 50, said it was a reality that loomed larger in their lives every year and threatened their living.

“We can only catch fish. We can’t do other jobs, so we have no choice but to endure it,” she said.