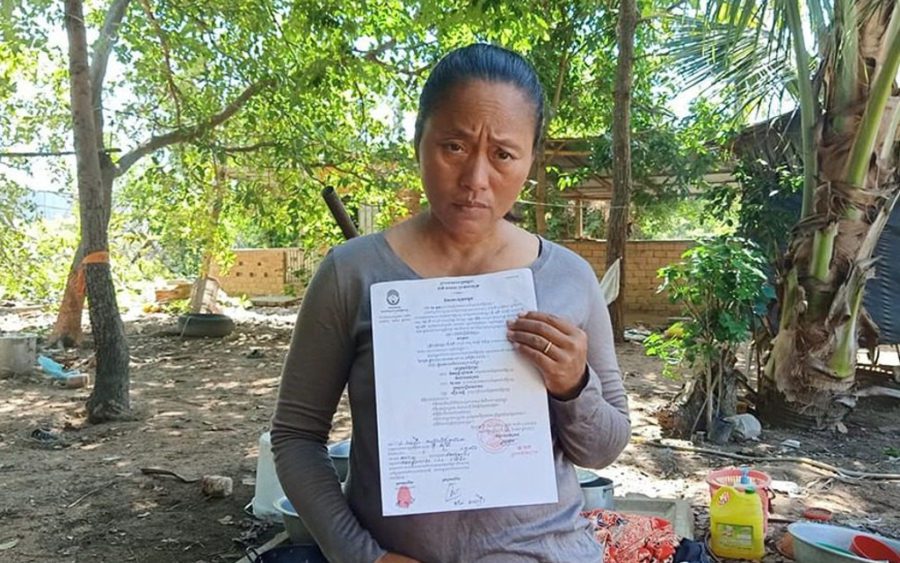

Oum Sophy has been locked in a land dispute with a government minister’s wife since 2007, and had an incitement charge hanging over her since 2008 — one of more than 12,000 stalled cases that had been stuck in the country’s justice system.

Over the intervening decade, her house was bulldozed; she was forced to move and change jobs; and she clashed repeatedly with military and police while leading protests over the dispute in Kampong Chhnang province’s Lor Peang village.

Her court case was not resolved until last month, when the Phnom Penh Municipal Court finally handed her a guilty verdict and suspended one-year jail sentence, meaning she would not have to serve time in prison.

There have been several court summonses over the years, but her dispute with KDC International, co-owned by Energy Minister Suy Sem’s wife Chea Kheng, reached a court verdict as part of a new Justice Ministry campaign to process the thousands of delayed cases around the country. Last week, it said the campaign, started in May, had cleared 8,000 — or 63 percent — of the cases.

Keut Rith, newly appointed as Justice Minister this year, said there were numerous cases that had been stalled for seven or eight years.

“Let’s think about cases being kept for seven or eight years — you can’t talk about whether their trials are just or not,” Rith said. When judges and prosecutors allow so much time to lapse, “it is already an injustice for the parties in the case, and the justice that they’ve waited for for so long becomes meaningless.”

Speaking at the opening of a new Appeal Court in Sihanoukville on September 3, Rith urged judges and prosecutors to continue to clear old cases “quickly, correctly, with justice and without corruption.” He added that he considered the accumulation of stalled cases simply a result of Cambodia “not being an advanced country with enough resources,” and estimated the campaign could be finished by early next year.

Defense lawyer Sam Sokong said the delays had been caused by judges who did not take cases seriously, took bribes to let cases die, or were new to a district and did not want to take up old cases from before they arrived.

“When we prolong the cases, it impacts the accused’s [rights], and violates the criminal procedure,” Sokong said.

Am Sam Ath, monitoring manager at rights group Licadho, said stalled cases were present in practically every municipal and provincial court.

“We welcome the Justice Ministry’s campaign to clear up old cases,” Sam Ath said. “Stalled cases … make people lose faith [in the court], and also drive overcrowding in prisons.”

In a report released in 2018, Licadho said a third of the country’s nearly 26,000 prisoners at the time were in pretrial detention — some of them waiting years for a trial — amid massive overcrowding across the country’s jails. In early April, Interior Minister Sar Kheng said there were nearly 39,000 people in incarceration across the country.

Sophy, the land protester, said she would appeal the verdict against her, even after 12 years, as she still seethed from what she considers an injustice.

“I cannot accept it,” she said. “I have not damaged any company property — I was the victim of the company. … The company mistreated us and I lost my job as a teacher; my house was bulldozed and our people’s farms were razed.”