Just a few years after U.N. trade data showed evidence of a massive discrepancy in sand exports to Singapore, the Cambodian government has quietly resumed selling the commodity overseas.

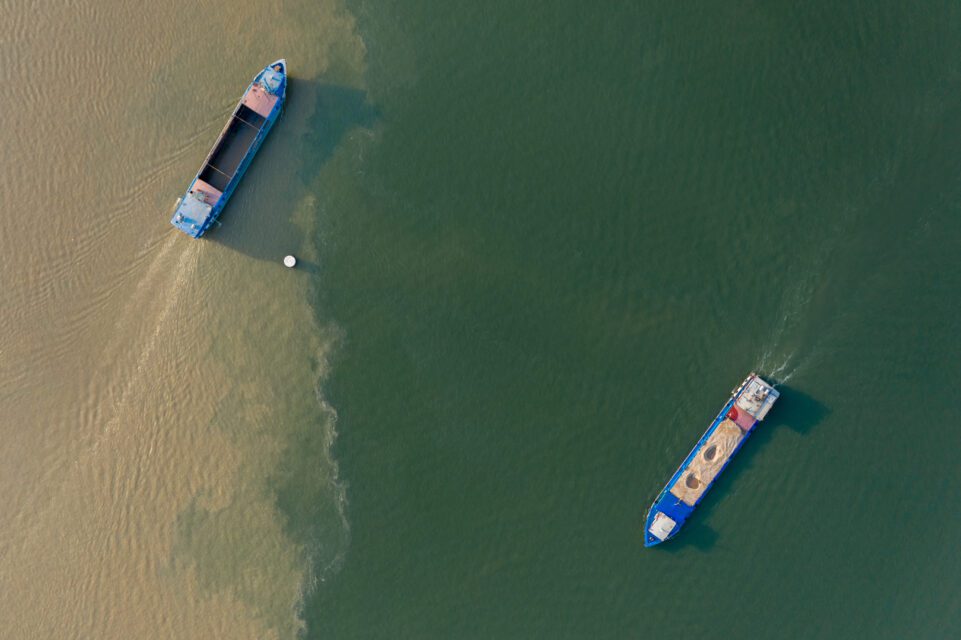

Last month, reporters watched a fleet of sand barges loading from the Mekong riverbed just within the border between Cambodia and Vietnam. Most of the barges flew dual flags representing both countries and appeared to straddle the demarcation at Ka’am Samnor border crossing in Kandal province.

Ung Dipola, the director-general for mineral resources at the Ministry of Mines and Energy, was mostly forthright about the export industry when contacted by reporters.

“We had announced it one-and-a-half-years ago and we had held a press conference,” Dipola said, though he couldn’t remember exactly when that was. “Any country that has demand for sand, they can buy it.”

He told a reporter that he would provide statistics for the amounts of sand exported from the country, but did not.

Data from the U.N. Comtrade platform — the same used in 2016 by environmentalist group Mother Nature to reveal a nearly $750 million gap in Cambodia’s sand shipments to sediment-hungry Singapore over eight years — says Cambodia exported 797,218 metric tons of sand last year worth nearly $5.6 million.

Comtrade has export data from Cambodia for the years since 2017, when the government supposedly banned international sand shipments amidst widespread controversy generated by the records shortfall. The highest year for export revenues was 2018, when the shipment of just 45,793 metric tons of sand appeared to net more than $8.1 million.

Both the alleged fraud from 2016 and the banning of exports gained international media attention, so the resumption of shipments would have been a newsworthy event. But it’s unclear which Cambodian media were present at the press conference Dipola mentioned, which seems to have produced little, if any, news coverage.

Civil society groups also seemed in the dark about the move. Representatives of rights group Licadho and accountability watchdog Transparency International hadn’t heard of the renewal of exports.

Transparency International Cambodia director Pech Pisey said on Thursday his team was searching for more information about the industry.

“We would like to increase transparency and level the playing field in sand mining licensing; enhance effective revenue collection from sand mining, including the allocation of social funds for affected communities; and increase availability of key information on sand mining, including the mapping of all sand mining operations in Cambodia,” Pisey said in a message.

Alex Gonzalez-Davidson, the vocal founder of Mother Nature whom the state deported in 2015 and effectively exiled from Cambodia, was more dismissive of the export renewal.

“The regime is increasingly desperate for cash, and resuming exports of Mekong sand makes sense to the regime though not for the environment or local communities,” he said in a message to VOD.

Any country that has demand for sand, they can buy it.

Ung Dipola, Mines and Energy Ministry

Dipola had a more upbeat tone as he said the export renewal is already generating considerable returns for the government.

“Recently, we have collected $5 million. This is huge revenue for our state budget during the Covid pandemic,” he said.

Currently, Dipola said, the only export site is through the Ka’am Samnor border crossing. He said the stretch of Mekong from there to north of the Neak Loeung bridge, about 41 kilometers upstream, has sparse local demand for sand, which helped prompt the decision to ship the resource out of the country.

“The location has a lot of growing sand and this can impact the ships’ navigation,” Dipola continued, adding “some locations cause growing sand by changing the water flow to crush the other side of the river, causing collapse of the bank.”

Hydrologists have rejected this logic, saying it runs contrary to the long-term findings of their field.

Locals watch over Phnom Penh’s skyline as a sand mining barge drives by infront of a ferry crossing the Mekong. (Andy Ball/University of Southampton)

Locals watch over Phnom Penh’s skyline as a sand mining barge drives by infront of a ferry crossing the Mekong. (Andy Ball/University of Southampton) A depot site in the capital where sand is unloaded before being delivered by truck to infrastructure projects. (Andy Ball/University of Southampton)

A depot site in the capital where sand is unloaded before being delivered by truck to infrastructure projects. (Andy Ball/University of Southampton) Workers fill bags with sand pumped from the Mekong to protect a very recent riverbank collapse from further erosion. (Andy Ball/University of Southampton)

Workers fill bags with sand pumped from the Mekong to protect a very recent riverbank collapse from further erosion. (Andy Ball/University of Southampton) Sand mining barges flying the Vietnam flag and full of sand moored on the side of the Mekong. (Andy Ball)

Sand mining barges flying the Vietnam flag and full of sand moored on the side of the Mekong. (Andy Ball)

Reporters visiting Ka’am Samnor last month watched sand barges in various stages of loading and shipping sand into Vietnam. The barges seen from shore flew dual flags representing Vietnam and Cambodia.

An empty barge driving upriver into Cambodia bore the names of two companies on its side, suggesting a joint venture. The visible part of one was “Cambodia Energy Development,” with Khmer signage indicating it was Global Green Energy Development, and Đông Dương, a Hanoi firm that mainly specializes in wood flooring and other interior design elements.

Though its Facebook page is mostly given over to Vietnamese-language posts about the flooring side of the business, Đông Dương also advertises Cambodian sand for sale. VOD called a phone number connected to the sand posts multiple times, including with a Vietnamese speaker, but either the line was cut or reporters could get no answer from the person who picked up.

Dipola said there are two Cambodian companies — Global Green Energy Development, which was chaired by family members of powerful tycoon Try Pheap until December, and Chaktomuk Resources Supply — exporting sand.

One of these firms working on the logistical end is the IBCO Group, a Phnom-Penh-based company with Vietnamese roots. Operating out of a nondescript office in the capital’s Chamkarmon district, IBCO has posted a considerable amount of information on its website about the renewal of exports, including what appear to be export licenses and customs invoices dating back to May 11, 2020.

A representative of IBCO who said his name was Max said the group facilitated sand exports from Cambodia to the ports at Ho Chi Minh City.

“If you want to send sand to another country, it has to go through Vietnam,” he said over the phone, explaining that companies need to commit to buy at least 1 million tons of sand to get an export license from the Cambodian government.

Max said the government was selling sand for a cheap price, and companies were welcome to try to enter the business on their own. However, he described a landscape of hidden fees and outstretched palms from contractors and minor officials of all stripes — on both sides of the border.

“With the government, you need to work with the big boss,” Max said. “The local people will charge you very high, even if you have the license for export.”

Max said IBCO could guide a would-be exporter past those hurdles, beginning with the first step of obtaining a license to export. While obtaining such a license directly from the Cambodian government might require a $1 million deposit, he claimed IBCO could do it for about $600,000.

“You ask why we can do it easier? Because we have the relationships, bro, both in Cambodia and in Vietnam,” he said. “You can do it by yourself, but I am sure you cannot get that price.”

By the time the process is over, he said IBCO can help exporters with the paperwork, labor and machinery needed to ship sand into Vietnam. Though Vietnam has a large domestic need for sand, exporters may instead make use of the Ho Chi Minh City port’s large size to fill 40,000-ton vessels. That’s the preferred size to send to any of 20 countries to which Max said IBCO has facilitated exports, though he did not specify the countries.

The Comtrade database doesn’t have statistics for the mass of sand exported in recent years from Vietnam, but does say the country shipped out $14.8 million of the resource in 2020, and about $17.6 million the year prior.

Max described the Cambodian renewal of exports as a prime business opportunity, but declined to say how much sand the company helps to ship in an average year.

“It’s a lot, bro. But don’t worry about that,” he said. “You just worry about the time, because the policy can change at any time. So we must do it as fast as possible, maybe a half-year, or one year or two years — it depends.”

Additional reporting by Andy Ball and Mech Dara

Correction, October 28: This article previously said a company’s name written on the side of a sand barge was “Cambodia Energy Development,” but this signage was partially obscured. Khmer writing alongside indicates it referred to Global Green Energy Development. An earlier version also said tycoon Try Pheap’s family chaired Global Green, but the company’s directorship changed in December.