Every afternoon for years, Meas Thon read four pages of the Cambodia Daily. He borrowed a copy of the newspaper’s Khmer-language section from a central Phnom Penh cafe where he still stations his tuk-tuk while waiting for customers.

It was political news that he was most interested in.

“Their news was precise and straightforward. They published only the truth, not taking anyone’s side. Other local newspapers do not publish the truth,” Thon, 55, said in late August.

Since the Daily printed its last issue two years ago today, the driver has relied on TV, radio and Facebook for news, but said he misses reading the paper, which provided him with in-depth, critical coverage of Cambodian politics.

“When I learned that the paper was going to cease publication, I thought to myself there is no more newspaper for me to read. It has been a while now that I stopped reading newspapers. I miss it,” Thon told VOD.

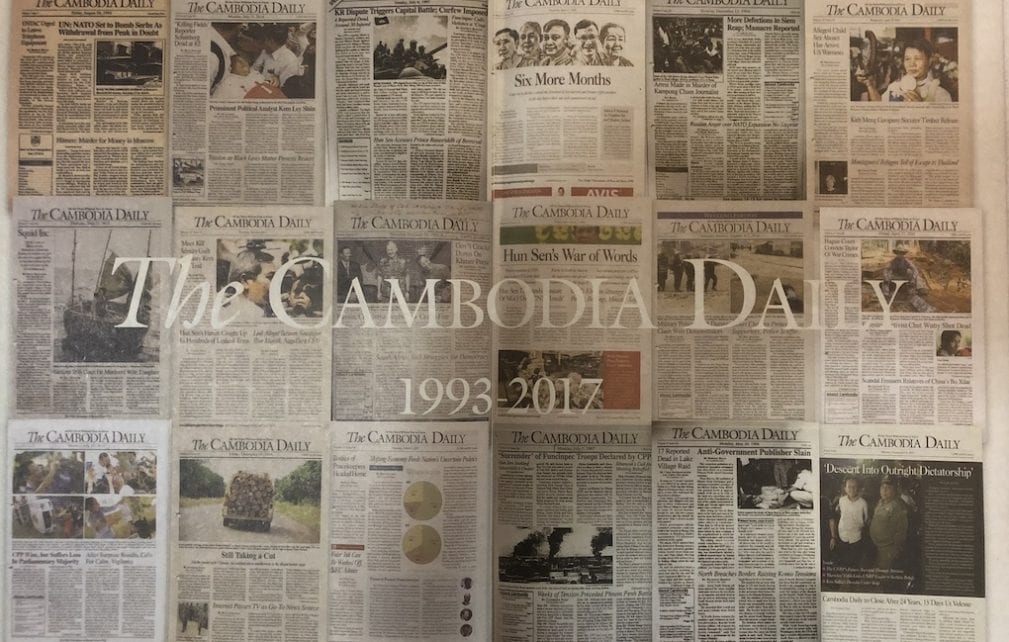

Founded by an American journalist in 1993 at a time when the U.N. was attempting to build democratic institutions in Cambodia following years of conflict, the Daily was one of the nation’s few news outlets that reported without allegiance to the government or government-aligned elites.

Its final issue hit Phnom Penh newsstands on September 4, 2017, after the paper was slapped with a disputed $6.3 million tax bill and told by Prime Minister Hun Sen to pay up or “pack up and go.”

With finances already dwindling and a tax settlement far from forthcoming, according to the paper’s management, the Daily’s owners chose to stop publishing and close its newsroom after nearly 25 years of reporting “all the news without fear or favor” — the tagline that emblazoned each issue’s front-page.

I feel I am only 50 percent informed nowadays about what is happening in the Kingdom.

Tassilo Brinzer, news publisher

Its owners have maintained an online presence, which mostly consists of aggregated news about Cambodia from other outlets, a far cry from the daily original news reports and analysis once offered by the print newspaper.

Political and media observers and free press advocates deemed the newspaper’s coerced closure part of a wider crackdown on independent media, the main opposition party and other voices critical of the government in the run-up to July 2018 national elections.

Former Daily readers last month said they missed their routine of reading critical, balanced news coverage of Cambodia. Many said their news diet had shifted — with some left hungry — since the newspaper’s closure, though some younger interviewees said they had never read a newspaper and had only heard of the Daily second-hand.

Journalists who worked for the Daily also expressed feelings of nostalgia, as much for the newspaper they produced, as for the colleagues with whom they worked long hours to provide readers with news that informed their understanding of the nation.

News Readers Missing a Routine

Khoun Theara, a research fellow and program manager at public policy think tank Future Forum, said quality news coverage of national politics, business and social issues has seen a decline in the last two years.

Without the Daily as a reliable source, he has turned to many local and international news sources to verify what he reads.

“I usually cross-check the sources of information with available yet limited credible media outlets in the country, on social media, and from credible sources and institutions,” said Theara, a former correspondent for Voice of America’s (VOA) Khmer news service.

“I miss reading the Daily in the old days every morning,” he said. “News features that I miss the most are investigative stories and long-form news analysis on some of the most sensitive and important issues.”

For Tassilo Brinzer, a German publisher living in Phnom Penh for 18 years, reading the Daily was also part of his morning routine.

“I do miss that what I could read in it was reliable, not biased and generally well-informed. It used to be the first thing I did every morning — read the Daily, and then other newspapers,” Brinzer told VOD.

He said there were still a few other good English-language news sources, such as VOA, that reported on Cambodia, but important news stories about the country were increasingly coming from international outlets.

“I am sure other investors and organizations feel the same — they can not make up a clear, well-informed view on the country and now need to learn about it from international news outlets,” said Brinzer, who publishes the regional long-form news website Southeast Asia Globe and luxury annual travel magazine Discover Cambodia.

Foreign outlets focused more on crises happening in the country and lacked a balanced perspective on “positive aspects” of Cambodia, he added.

Plus, the voice of the Daily was missed.

“I feel I am only 50 percent informed nowadays about what is happening in the Kingdom,” Brinzer said.

‘The Highest Standards of Journalism’

Today, some of the arguably most insightful international news coverage of Cambodia is reported by freelance journalists formerly employed by the Daily or its old rival, the Phnom Penh Post.

The Post, another once fiercely independent newspaper, was sold to a Malaysian businessman with ties to the Cambodian government in 2018 after receiving a hefty tax bill in a similar situation to the Daily’s. The sale and subsequent changes in editorial policies and standards, including the new management’s decision to remove a story about the paper’s sale from its website, resulted in a mass exodus of foreign and later Cambodian staffers.

While the two papers once competed for readers and scoops, the smaller, A4-sized Daily was better known for its snarky, hard-hitting tone.

Like the Post’s audience, Daily readers came to expect nuanced, investigative articles on government and business corruption and malfeasance, human rights violations, land conflicts and illegal logging, as well as coverage of voices who were critical of the government and otherwise often hushed.

Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodia Center for Human Rights, said the nation’s lack of an independent press left it harder to “hold public officials to account as a number of human rights violations, social issues and corruption may no longer be brought to the spotlight.”

The Daily’s reporting, Sopheap said, “met the highest standards of journalism” and the paper’s closure was “therefore felt as a great loss for everyone in Cambodia.”

The analysis made via the Cambodia Daily, we notice it is just an analysis from a perspective.

Phay Siphan, government spokesman

But government spokesman Phay Siphan — who once told a Daily reporter that he read the paper “every day to find out what’s going on” — disagreed that quality news coverage was in decline.

While multiple media voices were important, the Daily’s closure meant the loss of just one voice and source of information, Siphan told VOD.

“The analysis made via the Cambodia Daily, we notice it is just an analysis from a perspective,” said Siphan, who was regularly quoted in the paper.

“It is not an analysis that is necessarily useful for the government and the society to accept. It is just about voicing an opinion,” he said.

The Daily’s closure was a voluntary decision and not politically motivated, Siphan argued.

The spokesman said he used to get calls from Daily reporters requesting comment once or twice a day, and still receives calls from former Daily journalists who now work for other publications in and outside of Cambodia.

“They are like a friend who continues to maintain a relationship with me in the journalism industry,” Siphan said.

The Daily’s Final Crew

The Daily’s final issue featured a front-page with the blaring headline “Descent Into Outright Dictatorship”; reporting on the overnight arrest of the main opposition president, Kem Sokha; and nostalgic tributes to the newspaper and people behind it.

The punchy, quoted headline came from a statement by Charles Santiago, chairman of Asean Parliamentarians for Human Rights, who was commenting on Sokha’s arrest.

“If members of the international community, including and especially donors, fail to speak up and take action now, they risk ending up complicit in Cambodia’s descent into outright dictatorship,” Santiago said.

Later, observers likened the Supreme Court’s outlawing of the opposition CNRP in November 2017 and the ruling CPP’s sweeping of the 2018 elections to the establishment of a one-party state.

Sokha’s arrest was “one of the biggest news events of the year,” Jodie DeJonge, the Daily’s last standing editor-in-chief, told VOD.

“We had gone in that day thinking we might be reporting about ourselves, about how the government has broken the Daily’s legs, and maybe it’s impossible for us to continue, but we had to cover one of the most important stories of the day,” said DeJonge, now an editor at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and based in Sarajevo, Bosnia.

“Until the end, we took that responsibility so seriously. We didn’t have time to be angry or sad. We had a job to do,” she said.

DeJonge, a former Associated Press editor who was hired as the Daily’s managing editor in June 2016 and became editor-in-chief in April the following year, said staff went into the newsroom every day and “tried to put out the best newspaper that we could.”

“There were so many things happening that were important for the people to have an accurate, truthful version of events,” she added.

Two years after the paper’s closing, about half of the Daily’s Cambodian editorial staff are still working in journalism and less than half of the foreign staff remain in Phnom Penh.

The Daily offered me the privilege to challenge those in power to be more accountable.

Leng Len, former Daily reporter

Two former Daily journalists who had “incitement” charges pending against them at the time of the paper’s closing, which resulted after conducting interviews in Ratanakiri province as part of the Daily’s 2017 commune election coverage, now live outside Cambodia.

Four other former Daily staffers, including the editors of this article, are now working at VOD.

While some remain in Cambodian newsrooms, including at the government-friendly Khmer Times and the Post, former senior translator Kim Chan now helps his wife’s small business at a Phnom Penh market. His main duty is to deliver orders of paint supplies to customers.

Chan, who is either 49 or 50, said he misses learning about news as it happened in the newsroom. He spoke vividly about his 22 years at the Daily, but now he is too busy to read news.

“[The Daily] was a place that provides news without bias to people. I miss my work, of course, but it seems impossible to return to the job because [the paper] has already shut down,” Chan told VOD.

“Compared to my work at the Daily, [my current job] requires more labor, under the sun and the rain. When I get very tired from delivery work, I think of the work at the Daily. The salary was fixed, but I was happy to go to work everyday,” Chan said.

“Journalist is an important job. They dig up truth for the people,” he added.

Another former Daily staffer, politics editor Ben Paviour, is now a reporter covering Virginia state politics for VPM News, a National Public Radio affiliate. The Daily was his training ground, but what he remembers most about the Daily are his colleagues.

“The Daily taught me most of what I know about journalism. The editors were rigorous and taught me a lot about how to frame stories,” Paviour, 31, said.

“I also formed friendships that I think will last the rest of my life. It’s hard to imagine I’ll ever have a job as thrilling and fun as working at the Daily,” he added.

Paviour said he hoped the “old Daily, the newspaper with a quirky hard-working staff” could find a second life someday, but it didn’t seem likely right now.

Still, he wondered what was happening in the country that was no longer being reported on.

“Who knows what’s going on in Cambodia that’s being missed?”

A Founder’s Vision

While the print newspaper had ceased publication, it was too soon to speak of the Daily’s legacy, said publisher Deborah Krisher-Steele, the daughter of founder Bernard Krisher.

Now registered as a nonprofit organization in the U.S. and relying on donations to operate outside Cambodia, the Daily’s Khmer-language website still publishes original text and video reports, Krisher-Steele said. It also offers “Idea Talk,” an hourlong talk show program focusing on in-depth and analytical news that broadcasts daily on the outlet’s Facebook page and YouTube channel.

The English-language site publishes aggregated news about Cambodia from local and international publications and functions as an archive of the Daily’s past reporting.

“It is a different medium and a different format, and it stays true to my father’s vision, which was to provide very accurate facts and news to Cambodian people that are reliable,” Krisher-Steele said.

Krisher, an American journalist and philanthropist whose organizations have supported schools and hospitals in Cambodia since the 1990s, died in March at the age of 87, according to his obituary, which was published on the Daily’s website.

While the print edition’s Khmer-language section was only four pages of the typically 24- to 28-page paper, today the Daily is focusing on its Khmer news content and on Cambodians as its prime audience, Krisher-Steele said.

“I hope one day we can move our production back to Cambodia. I don’t know when that will be,” she said.

Continuing Education

Another former Daily reporter, Leng Len, is currently living in the U.S. while she pursues a master’s degree in media and education at Syracuse University in New York state.

After the Daily closed, she worked as a freelance reporter, fixer and translator for international outlets, but says she misses the Daily newsroom and her colleagues.

Editors “always had a high demand for our story or else you would receive a phone call from your editor at 10 or 11 p.m. for verification, more details, concrete details,” Len, 27, said.

“I miss hearing my colleagues calling and challenging our sources for comments. The Daily offered me the privilege to challenge those in power to be more accountable,” she added.

Before working for the Daily, Len interned at the newspaper for two months, but was first introduced to it in her grade 10 English class.

As a university student while staying at Harpswell Foundation dormitories, which provide housing and educational support for Cambodian women from the provinces while studying at Phnom Penh universities, she read the Daily even more.

English-language newspapers, including the Daily and the Post, were required reading for students learning English and critical thinking skills, according to Moul Samneang, the foundation’s country director.

An extracurricular Harpswell class was dubbed “CD class” or “Cambodia Daily class” because the newspaper was the main assigned text, Samneang told VOD.

“Everybody knows that the Cambodia Daily was a quality newspaper, reported the news that was true and unbiased,” she said. “Students need to know what is happening in their society and the world to be critical thinkers.”

Now, Harpswell residents are encouraged to read international news online, including CNN, BBC, Radio France Internationale (RFI), VOA, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, VOD and Women’s Media Centre, Samneang said.

I do not read much about [domestic] politics in Cambodia, because I feel like it’s going nowhere. It has been the same.

Thon Sreyoun, university student

But other university students in Phnom Penh say they don’t read newspapers.

Soung Sreyvin, a 20-year-old freshman at Pannasastra University of Cambodia (PUC), said she gets her news mostly from Khmer-language magazines and Facebook, and had never read the Daily or any other newspaper.

She said she didn’t follow political news because her father, a police officer, told her “not to get involved in any politics.”

Sreyvin, who is studying TESOL, or Teaching English as a Second Language, said political news was not relevant to her major.

“But sometimes if there is a big controversial event taking place in Cambodia and everybody is talking about it, I would also follow that story,” she added.

Another PUC student, Thon Sreyoun, said she had heard of the Cambodia Daily, but never had a chance to read it in high school because she was focusing all her attention on passing the national exam.

Now 21 and majoring in international relations, Sreyoun says she started listening to Khmer-language radio RFI about five months ago and prefers listening to news, especially analysis of world politics, more than reading it.

“I do not read much about [domestic] politics in Cambodia, because I feel like it’s going nowhere. It has been the same,” she said.

A Former Editor’s Greatest Regret

While independent journalism and news has become compromised in Cambodia, the journalists affected by the Daily’s closure, and the professional compromises they have had to make, were the bigger concerns for Kevin Doyle, the Daily’s longest-serving editor-in-chief, who worked for more than a decade at the paper and still follows news about Cambodia from Ireland where he works as a researcher at Dublin City University.

Doyle said his greatest regret was that “very fine journalists have to compromise themselves and have to work in an organization” that is “pro-government, pro-party,” like most news outlets in the country these days.

A few Cambodian former staffers, now working at English- and Khmer-language newspapers, declined to be named in this story.

Despite the closure of the Daily and Radio Free Asia newsrooms in Phnom Penh, and more than a dozen independent radio stations, all under government pressure, a U.N. Development Programme-funded report released in August said that in Cambodia, media’s “civic space hasn’t shrunk — it’s been fragmented.”

“It isn’t a vast public square — it’s small groups led by trusted voices. And Cambodia has no shortage of these,” the report produced by Singapore-based media startup Splice says, listing examples such as news outlet Thmey Thmey, coworking business SmallWorld Venture and education website WEduShare.

The report notes some challenges facing media outlets and entrepreneurs in Cambodia, including that organizations are hiring fewer journalists.

“As print and broadcast newsrooms cut back on staffing — or close down — there are fewer positions available,” the report says.

Splice suggests user-centricity, audience targeting and other audience-focused skills as solutions for the sector.

For Doyle, the former Daily editor, the newspaper itself was a model for “good journalism.”

“It was not any one or two stories. In fact, over 20 plus years, we set an example of good journalism, very high standards, high professionalism,” Doyle said.

“I just miss not being able to understand Cambodia on an in-depth level.”