More than 200 Montagnard refugees fled the Vietnamese Highlands four years ago hoping to find safety in Cambodia. Today, only 28 remain, still detained in a Phnom Penh house and fearing for their future. Risking the ire of authorities, they spoke to Danielle Keeton-Olsen with an urgent plea for help, with translation in Vietnamese by Tien Nguyen.

When the unstable Wi-Fi finally holds up long enough for us to connect, a Vietnamese-speaking friend and I greet the man on the other end of the halting video call, an ethnic Montagnard who arrived in Phnom Penh after fleeing persecution in Vietnam four years ago. He smiles.

But in the next breath, he hurriedly says he will have to call back in 10 minutes.

It’s 4 p.m. — time for the police to line him and the others up for a daily headcount.

There are 28 Montagnard refugees left in Phnom Penh, all living in one sheltered unit of a borey rowhome on Phnom Penh’s outskirts. The number of Montagnards living in that house has dwindled from about 200 when they first arrived in the country more than four years ago. Beyond that, little has changed for the remaining 28 who have been allowed to stay in Cambodia but are almost completely forbidden from leaving their protected space. And at this moment, there are no signs that their status will change in the future.

After nearly five years under detained surveillance in Phnom Penh, they are anxious and afraid. They wonder if they will ever be allowed to be free.

When the Montagnard man* reappears on the video call, he tells his story. Years ago, he kept a coffee shop in Dak Lak province in Vietnam’s mountainous center, home to multiple indigenous tribes in Vietnam that were bundled together as “Montagnards,” or people of the mountains, by French colonizers. Since the end of the Vietnamese-American War, Montagnards had been targeted by the Vietnamese government, which was opposed to the group’s support of American soldiers during the war and their embrace of Christianity. In his hometown, he witnessed pressure put on other members of the indigenous group, and the government even prevented residents from getting the medicines they needed, he said. So he participated in the thousands-strong protests across Dak Lak and another Central Highlands protest, Gia Lai, in 2001, until he was charged and imprisoned for 10 years.

He was released after serving the full sentence, but he sought escape from Vietnam. He managed to take a bus from Vietnam to Phnom Penh with the support of nongovernmental organizations in Vietnam whose names he cannot remember.

Upon arrival in Cambodia, however, he was rounded up and penned in the house he lives in today.

“I wish to become a citizen of Cambodia. I want to live here,” he said, lamenting his continued detention.

“I am very sad.”

I first connected with the man about a year earlier. Since then, he has occasionally messaged me in broken English to ask if I had heard any new information about the future of Phnom Penh’s Montagnard refugees. But in June, his messages became more urgent: He reported that four Montagnards were returned to Vietnam. He messaged me again one week later, fearing the Cambodian police were preparing to send more members of his group back to Vietnam.

The 28 Montagnards who remain in Phnom Penh have managed to obtain refugee designation in Cambodia, through what appears to be a handshake deal between the Cambodian government and the UNHCR. Why the 28 were selected is unclear.

By reaching out to those outside their compound, they risk being sent back to Vietnam, where Montagnards reportedly still face tight surveillance and discrimination from the Vietnamese government. But having watched as 200 of his compatriots were deported before him, he feels he must take matters into his own hands.

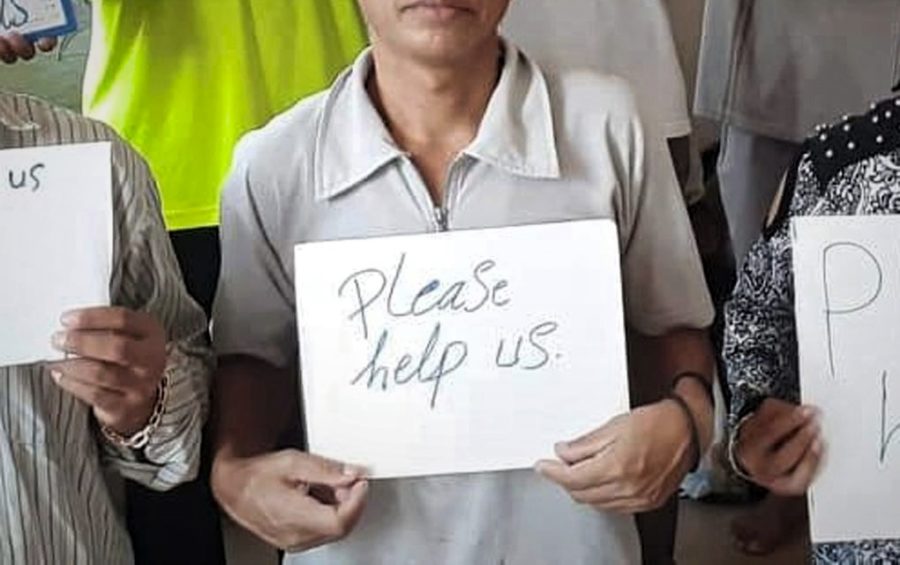

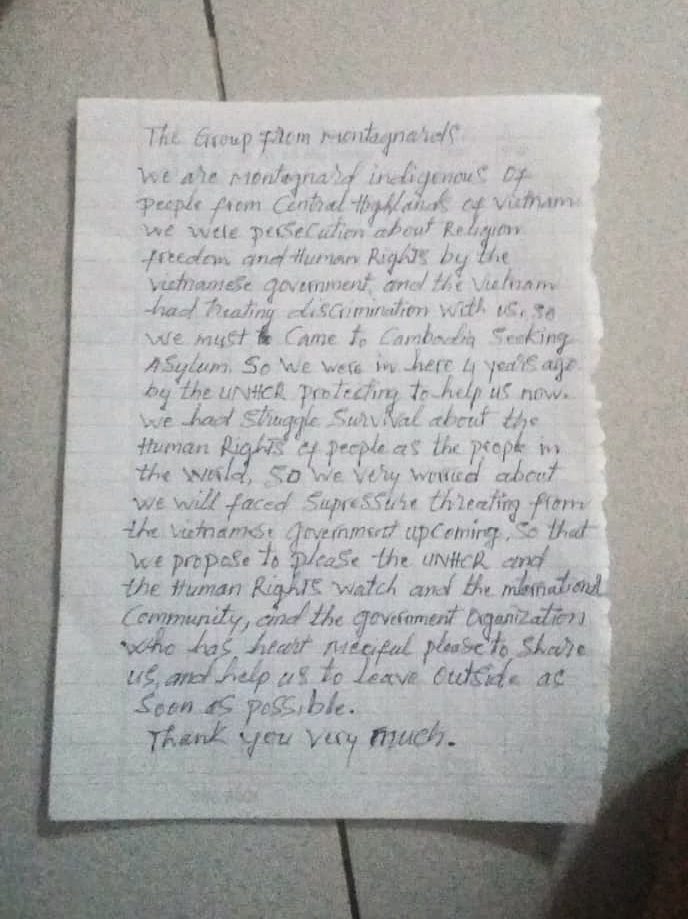

On June 23, he sends a photo of 13 of the refugees, including children, holding up signs: “Please help us.”

In an attached letter, they say: “Help us to leave outside as soon as possible.”

Montagnards reportedly starting crossing into Cambodia at the end of 2014, coming in buses across the border or crossing the mountains into Ratanakkiri province. Cambodian officials brought the asylum-seekers into Phnom Penh, then returned most of them to Vietnam in groups throughout 2016 and 2017.

After about two years of relative silence, the group of four Montagnards was returned to Vietnam in June. One of the residents had requested to be returned to Vietnam, while the other three, a family, had not received asylum-seeker status but were allowed to stay in Cambodia while the woman was pregnant, said Denise Coghlan, director of the NGO Jesuit Refugee Services, which contributes funding and services to the asylum-seekers.

Coghlan said last month that the 28 Montagnards remaining in Phnom Penh had received refugee status, but she did not want to comment further given the sensitive nature of their situation.

Cambodian law states that refugee status can only be canceled if it was found that a refugee provided fraudulent information, withheld information or asked to waive the status. Those granted refugee status should also be granted a resident card and extended the same rights and obligations as a legal immigrant foreigner, according to the 2009 subdecree on recognition of refugees.

Human Rights Watch’s deputy Asia director Phil Robertson said the Cambodian government could have issued exit permits to the group of 28 refugees to travel to a third country a long time ago, saying it was “beyond belief and explanation” why the Interior Ministry had yet to do so.

“To put it bluntly, there is no acceptable excuse the Cambodian government can give for continuing to hold them under de facto house arrest — and every day they are stuck in Phnom Penh is yet another day their human rights are being abused,” he wrote in an email.

“Quite clearly, the real villain in this entire saga is Vietnam’s brutal dictatorship which continues to pressure Cambodia behind the scenes to deny the rights of these Montagnard refugees.”

To put it bluntly, there is no acceptable excuse the Cambodian government can give for continuing to hold them under de facto house arrest.

Phil Robertson, Human Rights Watch

Though HRW has not been able to access the Central Highlands under the Vietnamese government’s strict control of the region, he said that interlocutors have noted continued discrimination against indigenous Highlands residents, particularly targeting, surveilling and sometimes torturing those who return from Cambodia.

“The situation is very dire, and Vietnam needs to end its campaign of suspicion, surveillance and abuse of the Montagnard people,” Robertson said.

Officials from the Interior Ministry’s department of refugees would not respond to questions on the Montagnard refugee population in Phnom Penh.

The Bangkok-based United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees supports the population living in Phnom Penh, supplementing the aid they receive from JRS, said UNHCR senior regional public information officer Caroline Gluck. She said the organization had also met with most of the returned Montagnards to check into their situation in the Central Highlands.

“When asked if they faced any problems, some cited financial or economic difficulties, a challenge faced by the community as a whole,” Gluck wrote in an email. However, those who return to Vietnam claim some have been forced into denouncing the U.N., though few journalists and rights workers can manage to enter the heavily-watched Central Highlands and verify their current state.

Gluck said the UNHCR was still discussing with Cambodian government officials to “seek solutions” for the Montagnard refugees left in Phnom Penh: One senior UNHCR official last met the government in early June, but she would not specify any options on the table. One of the refugees said a local UNHCR official brings food to them once a week, but he said the official does not give them information about their current situation.

The families’ life in Phnom Penh adheres to a strict routine. They have the opportunity to go to the market to buy food to prepare later in the day, and the children and adults receive English and educational classes from representatives from JRS, which donates funding and time in addition to an undisclosed contribution from the UNHCR.

At 3 p.m. they gather to pray. An hour later, the guard of the house counts the 28 residents. The residents at the compound previously reported as many as 10 police guards monitoring them early last year, but they just have the one right now.

Toward the end of our video call, I ask the Montagnard man if it would be possible to visit the house. But with an officer on guard, he fears that the refugees or I would only face trouble. Even if we tried to meet during their allotted time to go to the market, he could face problems by lingering longer than normal, he says.

Just after we hang up, someone calls back immediately. This time it’s a different refugee, a woman who comes from the same town as our main contact. She asks several times if we have had trouble with the police. She explains that a stranger had visited the house within the last few weeks, and the police had been stricter with them ever since.

“The police make a lot of trouble for us,” she said. “We don’t understand why.”

VOD could not get more information about this incident.

The woman repeats that she is a mother of three. Her children are detained with her in the compound. She starts crying as she asks for help, over and over again, before finally hanging up the call.

*The refugee asked that his name be withheld due to fears of repercussions in the future.