Three months after a Thai activist was allegedly abducted from outside a Chroy Changvar district apartment, neighbors say other Thai regulars who used to be seen in the area are no longer around, while apartment management denies the man had even lived there.

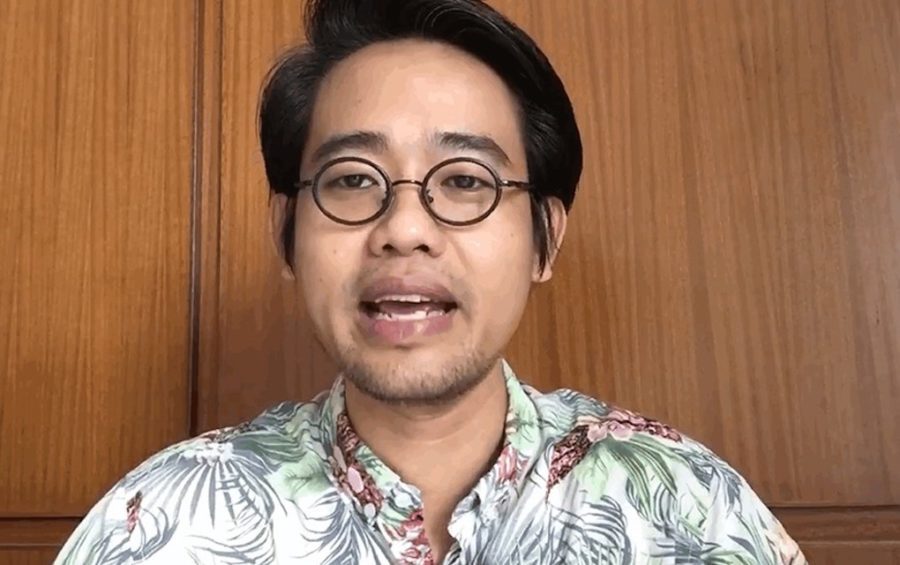

Wanchalearm Satsaksit, a 38-year-old dissident known for his satire and criticism of Thailand’s military regime, was allegedly abducted just before 6 p.m. on June 4, according to witness testimony collected by New York-based Human Rights Watch. Witnesses told the group that the pro-democracy activist, who had lived in exile in Cambodia since 2014, was returning from buying food outside his apartment in Chroy Changvar district’s Mekong Gardens condominium building when he was restrained and taken away in a black car.

Cambodian authorities have maintained that they have no leads in the case. National Police spokesperson Chhay Kim Khoeun told VOD last month that authorities found no record that Wanchalearm was living in the condominium, and the vehicle caught in surveillance tapes had an unregistered license. No other witnesses had come forward after their initial investigation, Kim Khoeun said.

Around the twin tower condominiums on Thursday, workers and residents were hesitant to talk about the man who was kidnapped in front of their homes, and most declined to give their names. Many said they were not worrying that a former resident was abducted three months ago.

Sokha Phal, a restaurant owner who opened up a shop a few doors away from the condominium about one month before the alleged abduction, said there should still be leads.

“It shouldn’t be hard to find [the suspect] — there are several cameras in every shop,” he said. Phal said he had not witnessed the incident himself.

A 22-year-old employee at a nearby store, who declined to be named for fear of harassment, said she had seen Wanchalearm stop in to buy goods, quick to smile but often alone. She said it was her day off when the Thai activist was arrested. There used to be other Thai nationals who came to her shop, but she had not seen any since Wanchalearm was abducted.

“Most people here don’t want to say anything,” she said. “Even if they know, they are afraid they [will be accused of] fake news.”

A security guard at Mekong Gardens said there had been four or five Thai residents living in the condo at the time that Wanchalearm was abducted, but they had all moved out since then.

The guard, who said he was interviewed by police shortly after the incident, was not on duty on the evening of June 4. One security guard witnessed Wanchalearm’s abduction, but that guard has been on leave for more than a month, he said.

An operations employee at Mekong Gardens, who gave his name as Sok, denied that Wanchalearm or any Thai nationals had been living in the building at the time, despite the activist’s sister, Sitanan, telling VOD that he did.

He also said that CCTV footage from the building did not show the incident. CCTV footage shared online captures the suspected car driving through the intersection that Mekong Gardens faces.

Sitanan Satsaksit, Wanchalearm’s sister, did not respond to requests for comment from VOD, but she told Thai news outlet Khaosod English in early August that she would travel to Cambodia as soon as travel restrictions ease, saying she had heard no update from either government on the case.

In the interim, Sitanan joined civil society organizations in Thailand and other family members of abducted activists last month to lobby Thailand’s House of Representatives on an anti-torture and enforced disappearances bill. Though the country signed the U.N.’s International Convention to Protect All Persons from Enforced Disappearance in 2012, domestic legislation has stalled.

Sanhawan Srisod, an associate legal adviser for the International Commission of Jurists’ (ICJ) Asia Pacific program, told VOD that a Thai national’s abduction abroad could be pursued under existing law that criminalizes attacks on a person’s body or liberty, but specifically criminalizing enforced disappearances would open up more possibilities to for victims to seek justice.

There are four versions of the bill floating through Thai government, with varying issues that the ICJ has flagged, Sanhawan said, but at its most inclusive the bill would consider enforced disappearances an ongoing crime, allowing the family of victims to take the case to court.

The version in Thailand’s House, which is scheduled for a vote in the next parliamentary term in November, would also include universal jurisdiction, which Sanhawan said would put pressure on both the Thai government and international authorities to investigate when a disappearance occurs in another country.

“Anyone who committed an enforced disappearance outside Thailand, regardless of nationality of the offender, … could be punished in Thai law,” she said. “This is quite a big move for this draft, because it’s not just about Thai suspects or victims.”