Siek Mekong believes the people aren’t pulled by the currents of party politics in Srekor commune. His commune has weathered floods, a rift in a village, and resettlement, and he served for five years as commune chief throughout it from 2012-2017, first as a Sam Rainsy Party candidate and then for the Cambodian National Rescue Party, until he lost his role with the opposition’s dissolution.

This year, Mekong is running again under the Candlelight Party’s banner.

When reporters met him in Stung Treng city this month, he could only meet in brief visits, saying he was feeling sick, likely from all the work he’s been doing in preparation, he suggests. At a Candlelight Party gathering ahead of the campaign’s start, Mekong takes a natural remedy of spoonfuls of lime and natural honey he says he harvested himself from Srekor commune.

Even when he was feeling ill, Mekong is confident he can improve insufficient infrastructure and fix the inequality in his commune.

“I want to stand as the candidate. I want to change the system,” he told reporters. “The discrimination, I’ve seen it really hurts [the people].”

Breaking the Currents

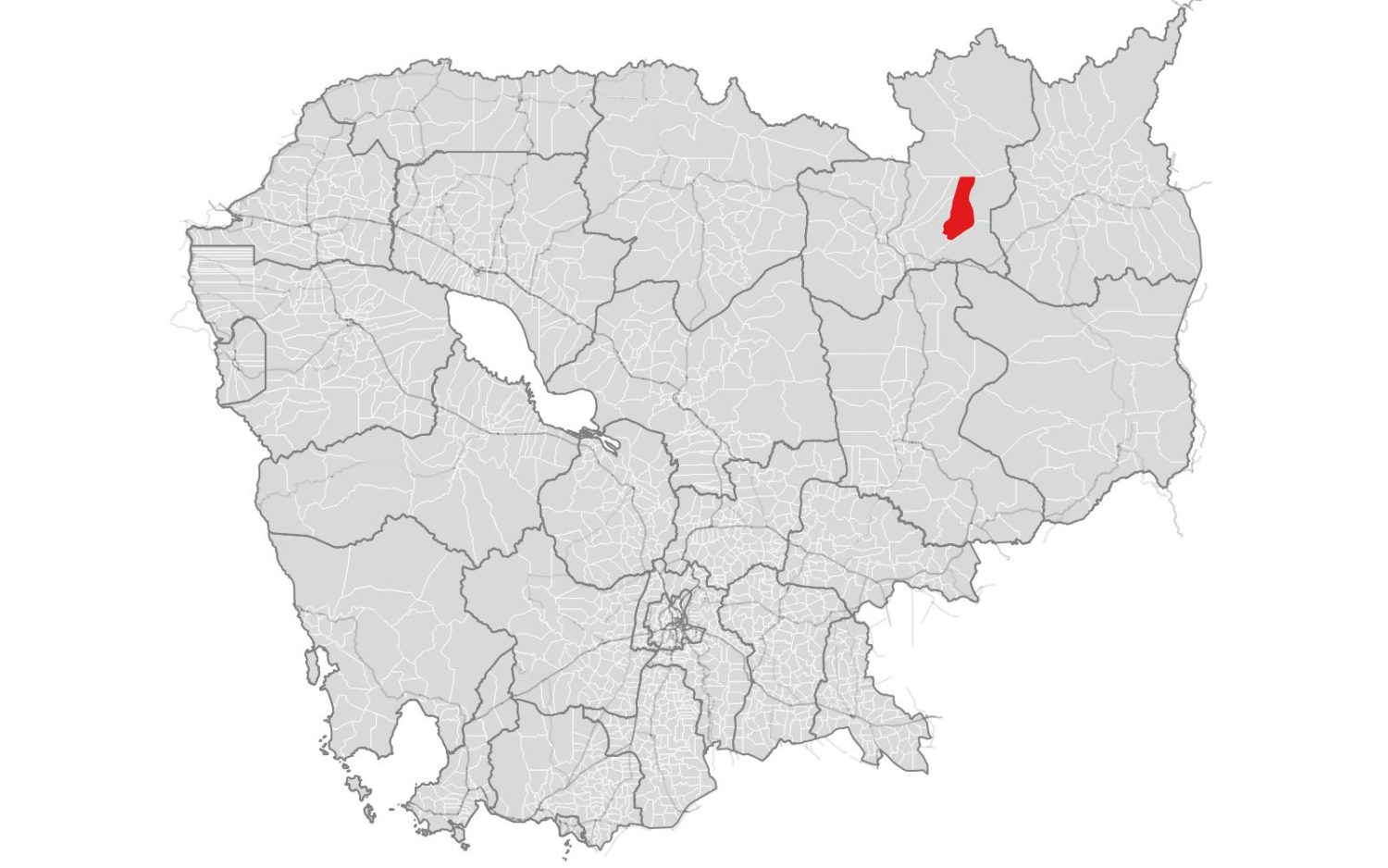

Both Mekong and his ruling-party rival, Foeun Choeun, live in Srekor Thmey village, a community of around 200 houses created six years ago when the Lower Sesan 2 Hydropower Dam development displaced them from their original home, now called Old Srekor, or Srekor Chas.

Srekor Thmey is a grid of stilted houses — all dark wood and topped with blue tin roofs on plots around 20-by-50 meters — given to the people of the former Srekor village, which was flooded in the name of more electricity.

Mekong first became commune chief in the original Srekor village, before it split — most chose to move to the resettlement homes stamped out in rows of Srekor Thmey, but a few dozen people created their own resettlement site, Srekor Chas, much closer to the old village and the ancestral forest that was flooded when China Huaneng dynamited the Sesan river to create a hydropower dam reservoir.

While his father is from Kampong Thom, Mekong’s mother is indigenous Lao — like most of the residents in Srekor Thmey — so the land under the reservoir was also important to his family. But he felt if he wanted to continue his role in local politics, he would have to move to the new village.

Mekong sees a divide in the way that members of the community are treated. He is aware that some people still have not received full compensation from the company, getting only a stilted house but no land to do agriculture.

The divide is evident from the state of houses: Some have been renovated, replacing the original blue roofs or dark wood walls with stronger materials, or building walls around their open-air kitchens. But some of the houses seem to have received no improvements. And some of the resettlement houses are empty, with closed doors and no chairs or farming equipment under the base of the house, maybe abandoned for years.

Keut Sipha, 24, says his family had everything in the original Srekor village — fruits, vegetables and water all close to their homes — but in this new village his family lacks.

“The [new] house was just built to be a house. It’s leaking,” he says, noting that rain enters the room where his family sleeps because the roof and siding are not tightly joined. “The old house is flooded, so where should I live?”

Sipha is still waiting to see if local officials will grant him a piece of land to cultivate. The only way he gets by is cultivating potatoes on a piece of land near his parents’ home, far from the resettlement village. He has also asked the current commune chief for an IDPoor welfare card to help with health care costs and Covid-19 benefits, but he wasn’t able to get one, being told those cards were only given to pregnant women or homeless individuals.

“They say they will share land after the election is done,” he says. “[It’s a] 5-year-old promise already, but still we do not see the land.”

Sipha and his wife are hoping for the IDPoor card from the commune chief so that they can go to the hospital for free.

Sitting among his wife and a few visiting neighbors, all chatting in the Lao indigenous language, he says he knows he’s obligated to vote. He says there is a person he knows he must vote for, but he wants to see a change in leadership.

When it comes down to it, Sipha says he’ll vote for whoever will finally grant him land.

Two Reelection Campaigns

Before reporters visit Srekor Thmey, Choeun, the current commune chief and incumbent candidate, says he is busy preparing for the elections. He says he is holding campaign events, without going into detail about his platform for reelection.

Reporters attempt to meet him while in Srekor Thmey and since have attempted to call Choeun multiple times, but he could not be reached after the initial contact.

Some residents say they support the current commune chief, including Sin Sreyneth. From her little shop selling sundries and nom krok, or round rice-flour dumplings, she sees that he has improved the roads and helped the community settle disputes.

Sreyneth says her husband, a truck driver who transports timber and goods, has been helping Choeun campaign.

“He helps the people,” she says of Choeun. “Like [building] a small bridge, or roads. He’s good at solving the people’s issues.”

Chuon Puon, 60, says he’s happier in the new location, where he now has more land to grow potatoes, and a buyer will drive into the village and pay him for the crop. He doesn’t like that they’re so far from everything else, having to drive across a long highway constructed over the flooded river and passing under some of the hydropower dam construction.

“I want a bridge to get to the other side,” he says. “It’s difficult. It’s far away to cross the hydropower dam.”

The residents of Srekor Thmey made a tradeoff by coming here, explains Ho Vei, 30, as she peels garlic and answers questions during a short lull in customers at her restaurant.

She and others have more land for farming than before, and some have been able to renovate their houses — hers transformed to a restaurant, drink shop and fried banana stand.

There are some problems on the land though, Vei notes. The prices for selling crops as a farmer are not always ideal or stable, and Srekor Thmey farmers have the added barrier of the hydropower dam.

“When they want to buy the potato, [the buyers] still can access [our village], but it takes time.”

All Srekor Thmey residents interviewed by reporters also complain about water. This is a problem since the resettlement, explains Vei, the restaurant owner: They had access to water in the old village, before the water drove them out.

There’s water in the hydropower dam reservoir, but it’s not clean and is distant from villagers. Instead, villagers are forced to buy water. Deng Seiha, 39, says the water is the only problem he sees in the commune, and he hopes the candidate he votes for will lower the price.

“I only want water. Only water is an issue,” he said. “I buy it everyday — it’s expensive.”

Seiha adds he has no complaints with the current commune chief, and he would vote for Choeun again. He later notes that he is a nephew of the chief.

Choeun’s campaigns have also included small giveaways: Puon, the 60-year-old farmer, says his family received sarongs from Choeun’s first meeting with the community, and 20,000 riel at the second meeting. When asked who he’d vote for, Puon isn’t sure who to vote for yet.

Five Years Resettled

Mekong is hoping he can win in order to pursue some of the goals he wasn’t able to complete by 2017. He set out to build a market that year, and he’s hoping to pave the village’s red-dirt roads, which is also a campaign promise of Choeun.

“When people have five or more [extra] banana flowers or any other vegetables, they would be able to sell them [at the planned market] to make money. But my plan was stopped when [the CNRP] dissolved,” Mekong says. “The new commune chief, he didn’t continue my plan for the people, to my disappointment.”

He also has loftier plans he hopes to bring back: to build a bridge that would allow villagers and visitors to cross the Sesan river without going into the dam company’s territory, and the four checkpoints it requires passing.

When asked if he thinks he can really do that, Mekong is again confident. He says he has a good working relationship with Energy Minister Suy Sem, after he helped the people relocate as hydropower construction progressed.

While Mekong is keen to cooperate with ruling party officials, he balks at the idea of joining the party in order to accomplish his goals for Srekor commune.

He mentions one of the Candlelight Party’s billboards was destroyed in his village, hit by a truck. Mekong believes it was meant as an attack on the party: a poster advertising motorbikes for sale next to the party banner was not damaged, and the car cleanly crashed into the Candlelight sign and was able to drive away easily.

“This is one of the threats to us. I have reported it to the police, but they never find” any culprit, he says. This was the only act of alleged intimidation he’s seen against the Candlelight this year, but he says he’s been an opposition member for 20 years, and the threats against opposition left him feeling “all kinds of bitter and sour.”

“I don’t like them. Violating, threatening their Khmer [people]. I don’t like it,” he says. “I have seen the court system is corrupt. Studying and the exams are all about money. I think about this, and I’m not happy.”