On February 1, just days before her 3-hectare rice farm was due for harvest, Sya commune resident But Pov was one of six people arrested and detained for 48 hours for farming on protected flooded forest near the Tonle Sap.

Pov, a commune council candidate for the opposition Candlelight Party, was ordered to destroy the hut overlooking the rice farm that had been her main source of income since 1984. “I couldn’t believe it,” she said.

Like others affected by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s recent decision to return certain flooded forest areas to longtime farmers and fishers, Pov could soon have a chance to start farming again. But it comes with a catch: The candidate alleges that commune authorities told her relatives she’ll only get the land back if she drops out of the race.

“People living here, it’s like living in a cage,” she said. “We can’t express anything or we’ll be threatened or jailed. I sometimes find it hard to continue living.”

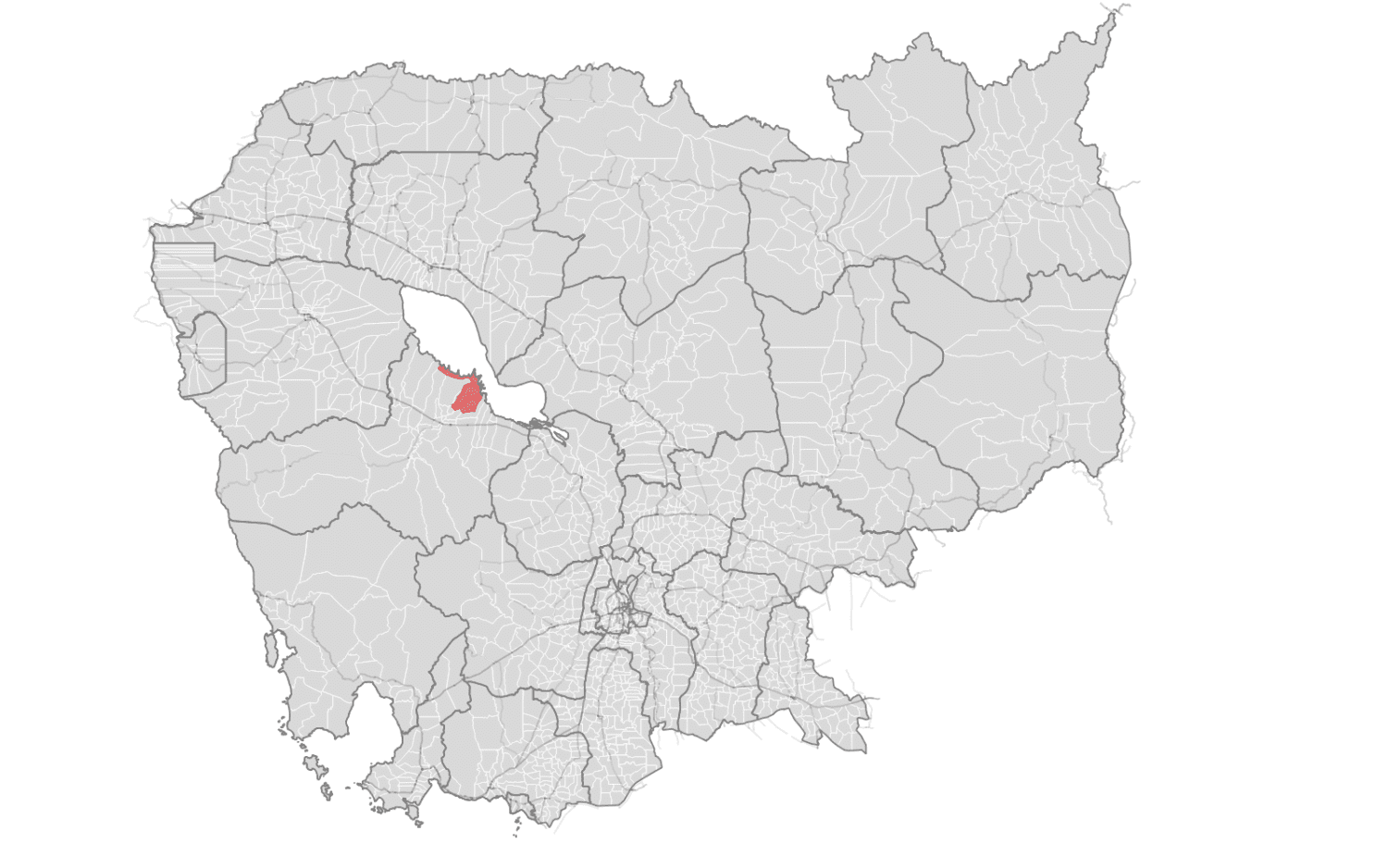

It’s one of many conflicts playing out across Kandieng district in Pursat province, where people in three communes described living through a crackdown on flooded-forest farming and fishing that seemed inconsistently applied and designed to intimidate, in several cases becoming intertwined with politics in the days leading up to the June 5 commune election.

Many acknowledged illegally farming or fishing in protected “Zone 3” land, and that the crackdown had reduced illegal activities. But also said they only did enough to get by and that authorities have implicitly or explicitly allowed their activities for years.

“It is illegal, according to the law,” said a sympathetic ruling Cambodian People’s Party councilor, Soy Keo, living in Reang Til commune on the edge of the lake, where three people recently had their boats or equipment confiscated. “But if we don’t fish, we don’t have anything to eat, and we don’t have land or rice fields like others — we fish to survive.”

Political Pressure

Pov is not the first Candlelight candidate to claim she is a political target in Sya commune, where most people fish in Pursat river or nearby ponds to make a living.

In mid-April, council candidate Hem Chhil and his 15-year-old son were arrested for using an electric fishing prod in their family pond. The family alleges that police fabricated evidence when they disappeared for 30 minutes and came back with a prod and battery that did not belong to him.

Since then, the court has not provided hearing dates or specific charges against Chhil, who has fallen sick with a fever in jail while crammed into a cell with 22 other people, according to his wife Van Nakry. Her son was released after more than two weeks on May 4.

“The next few days after, on the way to the family pond, I saw people fishing in the river with electric prods,” she said. “But they arrested only my husband.”

Police presence has increased from just two or three officers patrolling once or twice a month to five or six officers weekly, residents said.

Sun Noeurn, who is a relative of Chhil’s and whose mother-in-law has farming land in Zone 3, said he was told by family members attending a meeting to get the land back that the commune would only help “their people,” meaning supporters, find a solution.

“We have to go with the flow — whatever is possible to get the land back, we have to agree with them if we want to leave happily,” he said.

Candlelight candidate Pov meanwhile claimed that CPP-supporting relatives had passed several messages from the commune chief to her, including that she must end her candidacy to get the land back and pressuring her against speaking out about the dispute.

Commune chief Vin Ley denied the allegations and any suggestion of political motivations around returning flooded forest land to villagers, saying the decision is up to cadastral officials and alleging that those in the protected zone had been cutting down trees and expanding their rice farms.

He acknowledged sending a message to Pov’s brother but said that he merely pointed out the “good news” of flooded forest returns and asked what Pov felt about it. He claims her campaign was motivated by the flooded forest dispute.

“She’s been against us for a very, very long time, not just on this mandate but since Sam Rainsy,” Ley said. “She accused me by saying, ‘You guys are corrupt, you’re destroying the nation.’ Later on, it’s not me, it’s her herself that’s destroying the nation’s resources.”

‘I Don’t Know What to Do’

For many in Kandieng district, the promised return of flooded forest land doesn’t mean much.

In neighboring Kanchhor commune, Chhuy Chang, 32, and his wife, Pheng Sothean, 31, were called to a meeting with village and commune officials on May 28 and told they can start farming and fishing again on their 500 square meters of land.

Chang wasn’t comforted: The couple, who are raising twins after a decade of marriage, had taken loans to build a small hut on the plot of land and estimate that they now owe about 3 million riel, or $750.

“Now, during the election, we got the land back,” he said. “I’m stressed. I don’t know what to do. I just want to go to work outside [the village].”

About an hour away in Reang Til commune, which falls entirely under Zone 3, many families face a similar dilemma. Located along the edge of Kandieng district, residents fish in the middle of the lake when the water is low and move further inland to flooded forest areas when it rises.

Although flooded forests provide residents’ main livelihoods, few own any land outright, meaning that the recent land return provides little security, said CPP commune councilor Keo.

On April 22, Kem Yun, 61, and his son-in-law were about to collect their full nets when seven officers from three different authorities arrived and ordered them to stop or be handcuffed.

Yun knows that the spot behind Prek Salet village where he and his neighbors were fishing that day is protected. But police have never expressed concern, at most accepting 800,000 riel or about $200 to look away, he said.

This time, officers confiscated his boat and the fishing equipment. Except Yun had rented them, putting him about 5 million riel or $1,250 in debt to the owner.

“We really, really have no idea what to do, because the new policy is very strict right now,” he said. “Fishing each day I get only 1 or 2 kilos. It’s not even enough for us to eat.”

What happened to Yun has left many scared but also at a loss for their next steps, the CPP commune councilor Keo said. The only alternative to fishing in the flooded forests is migrating out of Reang Til to work in construction, garment factories or banana plantations in Phnom Penh and Thailand.

For now, Yun is taking it day by day.

“We’ll just stay here until we can fish little by little every day and pay them back,” Yun said. “Hopefully they say OK. And if they don’t, we’ll be in trouble.”