Phy Kakada gets off her motorcycle outside a small house with freshly painted walls and wooden shutters on the windows. She walks in with a small packet of medicines and greets her 2-year-old son and baby daughter.

Kakada works at the nearby Huy Yon garment factory and is tired, but makes it a point to visit her children at the Chambak child-care center during her lunch break in mid-June. Phaneth, a 2-year-old, has the flu and is a little low on energy, while his sister Kim Lang is busy playing around the room.

The garment worker says the new center, which was opened in early May, reduced the stress of either finding a neighbor to help take care of the young children or having to pay for a babysitter — both with attached costs for families.

“In the past, I had hired a caregiver who lives across from my house but my children got sick every week,” Kakada says. “But after two months here, I find that they are healthier, cleaner, and talk a lot.”

The Chambak center is one of three being developed by NGO Planete Enfants & Developpement in Kampong Speu’s Samraong Tong district. The centers, in three communes in the district, rely on donor-funding to cover staffing and facilities costs.

The NGO says that only 13 of 700 garment factories in 2019 were in compliance with child-care provisions in the Labor Law: Factories above 100 workers are legally required to provide these services. It says factories prefer to pay workers a child-care allowance, which typically isn’t enough to cover the high costs of daycare services, rather than have on-site facilities. Private day care centers are too expensive for families, and public centers are mostly concentrated around big cities, the NGO adds.

A survey by the NGO found that working mothers were worried about having to leave work to take care of their children, and that only two-income households were more likely to be able to afford child care.

The Chambak center has nine toddlers and four staffers, with a maximum capacity of 25 children. The center is open six days a week to match workers schedules but is only open till 4:30 p.m. — a closing time that has been too early for parents doing overtime at the factories.

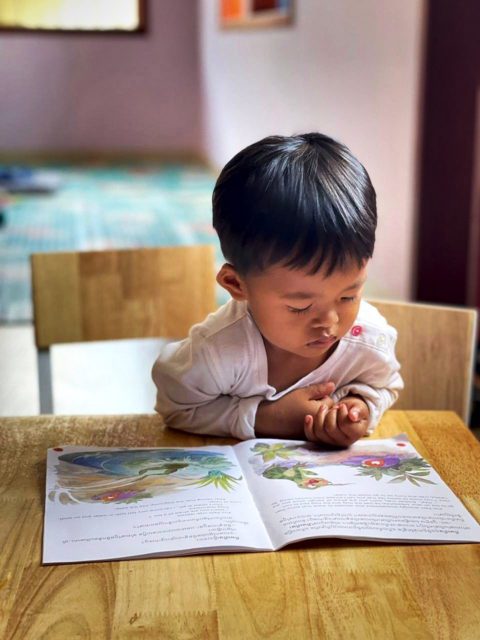

Sambath Sophal, a facilitator in Chambak, says the center tries to provide good nutrition with specially cooked porridges and instill good habits, including going without screen-time.

“Here, we don’t allow [children] to use phones, or even let children see phones. We keep the phones away,” Sophal says. “[One mother] says her child doesn’t ask for a phone anymore.”

Lo Sreyyan, one of the caregivers, says children come from various backgrounds, and there has been an adjustment period before they became comfortable playing with one another.

“There are naughty children and gentle children, so we must put all our effort and attention to them,” Sreyyan says. “When they are new here, especially when playing, normally they don’t like to share with each other. But we try to solve it by letting them share and play together.”

Kampong Speu parents VOD spoke to say that even though there is a cost attached to the services at Chambok, the center provides good care, is conveniently located, and they have seen improvements in children’s health and well-being. The World Bank has said that it is developing 22 such community-based child care centers for garment workers in three provinces under a $2.7-million grant program.

Mang Mam, the father of a 6-month-old toddler, walks into the center and inquires about how his daughter is doing. The father and garment worker says the center’s fee of $45 a month is on par with paying a neighbor to keep an eye on his daughter and cheaper than hiring a babysitter. The fee goes toward meals and other supplies.

The professional services provided by the center’s staff made it easy to not worry about his child every day, Mam says.

“There is a difference between hiring a babysitter and keeping my daughter in the center. In the child-care center, they take 100% good care and it helps me a lot to focus on working without worrying about my daughter’s safety,” he says.

Phy Soknoeun, another working mother, rushes into the center to meet her 3-month-old daughter and in a brief interview says her child was previously under the care of the grandmother. But during the harvest season, the grandmother had to work in the fields and was unable to take care of her son, Soknoeun says.

She is happy with the daycare center but wishes it is open till later to accommodate for overtime she puts in at the factory, she says as she rushes out of the center.

Eim Sinna, a manager at the center, says reception had been mostly positive, but there were parents who were potentially not using the services because of the early closing time.

“If the center could rearrange the closing time, more babies and toddlers would be sent here,” Sinna says. “But the project organizer cannot only [factor how] to help garment workers but is also worried about the care and safety of staff at the center.”

Kakada, the mother from the Huy Yon factory, says she is relieved that her two children are in a safe environment, allowing her to work without worry at the factory.

“When I hired a babysitter to look after them I didn’t feel safe at all, both about my children or my property,” she says, getting a little emotional. “But after sending my children here for two months, I feel so much more alive and have time to work.”