UPDATED — On the day he was arrested in March, Ouch Leng was confused by the path he usually took through the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary.

The anti-logging activist said he generally knows how to navigate adjacent to the dirt road that’s being carved into Prey Lang’s protected borders, but he was disoriented by new paths spidering further into the dense forest. That’s how he and three other activists ran into security guards from the timber company he says is building the road. The four were detained over a weekend.

The fresh forest trails, Leng said, suggest new illegal logging activity in the area.

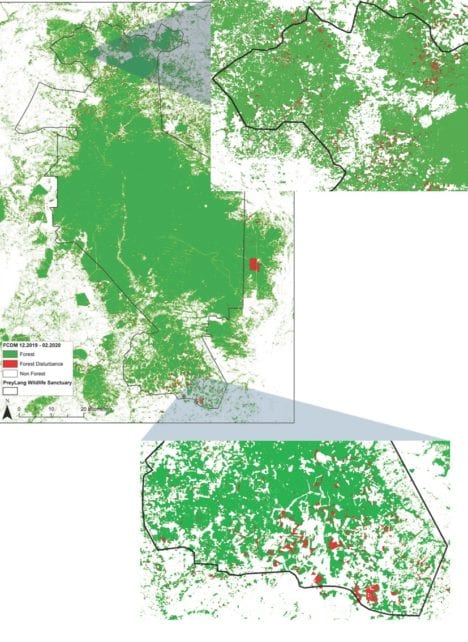

Meanwhile, hundreds of kilometers above his head, satellites were collecting snapshots that show a thickening line of deforestation inside the sanctuary in recent months, one that a researcher suspects was the company Think Biotech’s gateway to valuable, rare wood.

Forestry watchdogs say they have seen increased logging activity in the Prey Lang sanctuary, especially after independent forest patrollers were stopped by authorities from entering in February, but officials have defended their ban on unregistered forest patrols.

“We are patrolling the large-scale illegal logging, unlike other patrols conducted by other NGOs, who are just going for a walk inside the jungle and never patrol the companies at all,” Leng, a PLCN member, told VOD last week.

A Cambodian official and the head of a U.S. government-funded conservation program in Prey Lang also acknowledged that they were aware of logging occurring in the sanctuary.

On Tuesday, reports from activists on the ground were linked to evidence of new deforestation detected in satellite imagery and published in an open letter to Prey Lang stakeholders from Ida Theilade, a conservation scientist and University of Copenhagen professor who has studied the Prey Lang landscape for more than a decade.

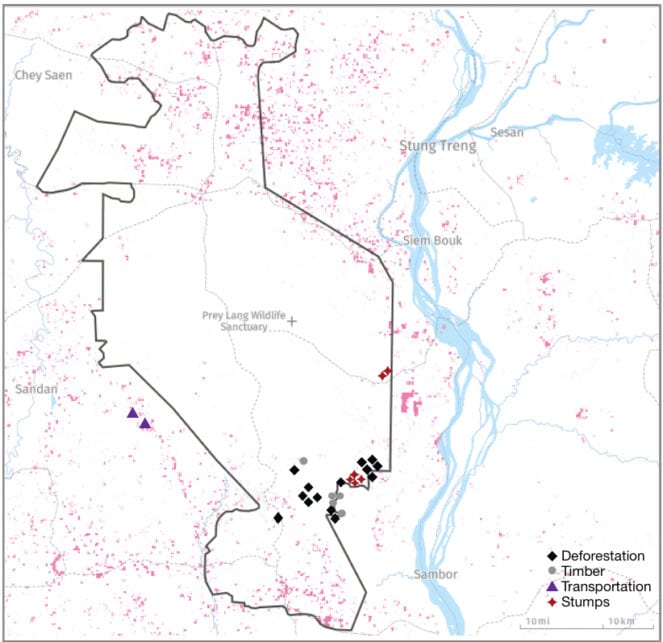

Theilade’s letter compares illegal logging activity records from Prey Lang Community Network (PLCN) patrols — which note sightings of stumps, cut timber, transport vehicles and cleared areas — with satellite images from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. The data and maps show recent clearings in the north and south of the 430,000-hectare sanctuary, and spikes in signs of deforestation at times when authorities maintained a presence in the protected forest and kept activists out.

For example, on February 23, two days after Environment Ministry officials and local authorities prevented hundreds of environmental activists and others from entering the Prey Lang protected area for PLCN’s annual tree blessing ceremony, Global Forest Watch (GFW) detected nearly 12,000 forest alerts, a notable jump compared to earlier weeks this year.

GFW, an online platform that uses satellite data to chart deforestation worldwide, reports about 1,000 alerts, or signs of deforestation, on average per week, Theilade said.

“Rapid forest loss has occurred in the area of the planned PLCN ceremony,” she says in the letter. “We are concerned that the PLCN tree blessing ceremony was banned due to government-sanctioned illegal logging of protected resin trees in the area.”

In response, Environment Ministry spokesman Neth Pheaktra said it was the researcher’s right “to express her opinion.”

“The Ministry of Environment is working actively with related stakeholders to protect Prey Lang including the co-patrols with protected area communities,” he said in a message.

Theilade told VOD that the satellite images captured from the end of last year till this month show that spots of deforestation follow a path, suggesting that there is a widening road connecting the protected area to Think Biotech, which holds a 34,000-hectare concession that borders the sanctuary in Kratie and Stung Treng provinces.

Think Biotech director Lu Chu Chang declined to answer questions before this article was published on Wednesday, but he told VOD on Thursday that his timber company was not associated with forest clearing that has been detected near the company concession in Kratie and Stung Treng provinces.

Lu denied that his company bought timber from the protected area, saying it uses trees from its own concession, and he wanted organizations to stop blaming him for logging when it’s the government’s responsibility to reign in forest clearing.

“Forestry officials, and the police and NGOs and the government check everything [in my businesses], but I don’t do [illegal logging], I don’t do any wrong,” he told a reporter during an interview in his Kandal office.

Lu, Chea Sankthida, another director of Think Biotech, and Chea Pov are also on the board of Angkor Plywood, a timber company and furniture manufacturer.

Environment Minister Say Samal called for an investigation into the two companies over alleged illegal logging in Prey Lang last October, according to the Phnom Penh Post, but Pheaktra didn’t answer questions from VOD about these companies.

“It’s a new development, but then again, Think Biotech has been in numerous reports for many years, connected to illegal logging,” said Theilade, the researcher.

She also noted that Greening Prey Lang, the $21 million, five-year project overseen and funded by U.S. development agency USAID, has released no public reports of increasing logging activity.

“As scientists, we are concerned that the multi-million dollar Greening Prey Lang project has either not detected the forest disturbance or has chosen not to communicate it to the public,” Theilade wrote in an email shared with reporters. The researcher said on Tuesday that a Greening Prey Lang representative had contacted her and asked to discuss her findings later this week.

Matthew Edwardsen, chief of party to Greening Prey Lang, told VOD on Tuesday that the USAID project was detecting deforestation, particularly targeting resin trees within and near the sanctuary. He said the project team had brought those findings to the government instead of publicly releasing reports, as researchers and activists have done.

“I wouldn’t say the project is creating this public record of deforestation and illegal logging trends; that’s not really an approach that we’re taking,” Edwardsen said. “What we’re trying to do is really build the capacity of the government, and to address these issues.”

He said the project started conversations with PLCN members more than a year ago to facilitate a joint patrol teaming government rangers with members from PLCN and other communities in the Prey Lang area, which he described as a difficult process.

“So basically [we want to] increase the number of patrols and increase accountability of patrols because you have community members and rangers going out together, and that just makes everybody potentially more likely to agree on what they’ve seen in the forest,” he added.

Ear Sokha, head of the Environment Ministry’s inspection department, acknowledged that illegal logging was occurring on a small scale in Prey Lang, but he declined to provide details.

Government rangers had worked with members of PLCN up until February, conducting joint patrols and keeping logs documenting incidents of logging and other forest crimes, Sokha said. But the ministry ordered environmental officials to work only with communities that are registered with the Interior Ministry, which PLCN has refused to do, he said.

“We acknowledge what they have done [to protect the forest], but then we had found out that what they did was not intended to be their personal sacrifice,” Sokha told VOD.

“They are a structured political body, and they don’t listen to us. We worked with them, and [we noticed that] as they patrol, when they could get money from illegal loggers they will be silent, but if they don’t get money, they would ask us to help [with an arrest] and then attack us,” he said, adding that PLCN had accused rangers of corruption.

Ek Sovanna, PLCN’s coordinator for Kratie province, denied the official’s account and leveled accusations of accepting bribes back at the authorities.

“On every patrol, we had patrolled with rangers, so if [Sokha] accused us of that, it sounds like he is accusing his officials too,” Sovanna said. “I think it’s just his excuse for his officers, because everybody here already knows what they do.”

Sovanna said he’s more worried about the forest now that PLCN patrols are banned, noting that he had observed tractors used to transport wood entering or leaving the forest “almost every day.”

After they were detained last month while patrolling in Prey Lang, two PLCN members; Leng, who heads the Cambodia Human Rights Task Force; and a fourth activist who was allegedly beaten by Think Biotech guards, were handed over to authorities and then the Kratie Provincial Court, though charges of theft and breaking and entering against the group were dropped.

Pheaktra, the ministry spokesman, told VOD at the time that PLCN was banned from holding their annual anti-logging event because they tried to enter a “core zone” of the forest, where only nature conservation officials or researchers with written permission were allowed to enter, according to the Protected Areas Law.

However, Theilade, the conservation scientist, said Prey Lang had never been zoned, and she would caution against designating the forest.

“What is so special about the Prey Lang [forest] is you have an assemblage of seven different forest types,” she said, describing the “mosaic” of evergreen, deciduous and swamp forests that she documented with a team of researchers in 2007.

She said that conservation biology and science suggests an area like Prey Lang should be protected as a continuous landscape, noting that PLCN had already been patrolling the forest broadly, and that it would align with indigenous Kuy people’s forest protection practices and traditional use of natural forestry products.

What’s most important, she said, “is that Prey Lang is not further fragmented and parceled up into isolated community conservation areas and other small patches of forest.”

Sar Mory, a research and advocacy program manager with Cambodian Youth Network, said his organization is still supporting PLCN, but both have decided to stop on-the-ground forest patrols and instead switch to monitoring the forest via satellite imagery.

Mory told VOD last month that the ministry invited PLCN to register as smaller community protected areas (CPA) for some time, but the organization did not want to be limited, like residents of CPAs are, to patrolling a small portion of the forest.

“The Ministry of Environment tries to set up a lot of mechanisms,” Mory said. “They try to convince the community to register, but they don’t think much about the effectiveness of forest protection.”

Updated at 4:40 p.m. with comments from Lu Chu Chang.

Correction on April 28: The article originally referred to Sar Mory’s position with Cambodian Youth Network as director. He is a research and advocacy program manager with the organization.