KIRI SAKOR DISTRICT, Koh Kong province 一 Whenever a resident needs to leave Ta Ni village, one person has to stay behind and watch the land. If not, the ever-present security guards could come with tools, sometimes guns, to take apart their homes.

Meah Ream, 58, says this has been the fear for over a decade, as security guards frequently drive boats past the land she claims among the ribbons of curving, connecting rivers that empty into the Gulf of Thailand.

Just four days before reporters visited on June 28, the guards came again, tearing boards and metal from her hut until it was left as only a wooden platform.

“At the time of the attack I was picking small fish for pickling,” she says. “We were just trying to build a house on our plantation.”

Ream says she’ll rebuild the house, but for now she and her family relax on the wooden platforms still standing on sandy shores, chatting with other families who, like her, say they are constantly moving and building to get around the antics of the guards from the Union Development Group.

Grand Plans

With its expansive stretch of national park, mangrove forests and scenic coasts, the Union Development Group has promised audacious plans for its 45,000-hectare concession covering 20 percent of the country’s coastline. But after a decade of development, the western coast still feels undisturbed by those plans marked for its shores, and satellite imagery reveals only small pockets of development.

The company’s website dreams up limitless potential for the area — industrial zones, seafood and agriculture processing plants, a health care center specifically for Chinese people and “the largest film and TV production base … in Southeast Asia” — but offers very few specifics other than a hand-drawn map and illustrative images of developments.

Cruising along Botum Sakor’s west-facing coast, the main sign of UDG’s developments is a lengthy dock that stretches around 700 meters into the sea, based on measurements from satellite images. Other than that, the coast is bare, at least from a passing speedboat’s view.

That port and as well as an airport with a 3.2-km runway, which is ostensibly scheduled to greet its first airplane in the fourth quarter this year, have caught the U.S. government’s attention. Last September, the U.S. sanctioned UDG over purported Chinese military links and treatment of residents of the area. Since UDG was granted the concession between 2008 and 2011, 1,143 families were forced off about 10,000 hectares, with 1,500 houses dismantled and cleared away, according to a 2012 report by the Community Legal Education Center.

The Dara Sakor Seashore Resort has opened, accepted guests and remains listed on popular booking platforms like Agoda and Booking.com, but the hotel does not appear to have rooms currently available for rent on the websites. One of the phone numbers on the listed website was inactive, though a man who answered another listed phone number said the hotel was open.

When a reporter tried to visit UDG’s showroom in Phnom Penh, the office was closed and guards at the entrance said they did not have phone numbers for any staff. The two phone numbers that appeared on a poster at the showroom’s entrance failed to connect when a reporter tried to call this month. The company could not be reached on other available phone numbers, including those registered with the Commerce Ministry.

Elaborate models of condominiums and resort homes are still visible through the showroom’s sweeping glass windows, as well as a cardboard box of trash filled with empty takeaway meal containers and a broken vase.

The Communities That Remain

Chinese-language posts advertising the resort’s opening in 2015 also touted the tourism potential of the area, admiring the stretch of coastal mangrove forests for their stabilizing properties and natural charm, as well as a proposal to create an “ancient fishing village” among the company’s tourism and entertainment offerings.

The residents who live there say these are exactly the elements of Botum Sakor National Park that the company is destroying.

Nhan Phin, 53, lives in a row of homes along the estuary, their homes’ stilted foundations facing the mangroves’ raised roots. Phin says she’s just about done with fighting the company and would be willing to sell her land — but she wants market price for her 20 hectares, which she estimates to be around $700,000 for the prime coastal land.

She says that some of UDG’s security guards are from the Kiri Sakor district villages that are impacted by the company, but they need jobs and would lose them if they refused to destroy a home.

Residents of the land expected fair compensation and job opportunities, but the only jobs offered were that of security guards combating their neighbors. “They haven’t done what they’ve said. It’s just empty promises,” she says. “We think it’s time to take compensation and look for a decent house.”

But Phin qualifies her stated willingness to leave as she continues chatting with her neighbors among the wreckage of houses. She says no local officials have stood up for them, so they have to stand together against guards who come with tools and torches.

“We’ve tried to stick together and try to help each other when they demolish [houses]. When we unite, we don’t dare to do much though,” Phin says.

But the residents are all alone, she adds. “No one dares to come help us.”

One man, who did not want to give his name, says he would burn the boat of any guards who come for his house.

Keo Khorn says he’s still waiting for authorities to intervene. He was not happy when former Koh Kong governor Bun Loeut offered him 2.5 hectares of land elsewhere in exchange for the dozens of hectares Khorn has claimed over the years.

The 58-year-old says he would eventually take compensation if he felt it was a good rate, but for now he is aggrieved. He left his home to get a Covid-19 vaccine in late June. Trying to return, his family was stopped for an hour from returning to their home, a stilted house where he sells snacks and sundries to those boating down the estuary.

“How can they block us from going home? The baby was crying in the car,” he recalls, his voice rising as he recalls the event from a week before.

Khorn says the family has been stopped by authorities from farming their land, which is the main issue he hopes the current provincial governor can solve. The land has sat useless for at least two years, and even though he claims his commune and district land titles are in order, he cannot sell.

One day two years ago, Khorn claims a man arrived with a suitcase filled with $800,000 in U.S. dollars. The man wanted to buy Khorn’s land, but neither commune nor district authorities would approve it.

“It’s very difficult. We’ve spent a lot of money” trying to reclaim his land for use or sale, he says. “We can at least still go to see it.”

When asked about UDG, governor Mithona Phouthorng told VOD that she was too busy to discuss it: “I would like to elaborate about the work there later because it is in process.”

Run-Down Resettlement

The general population can drive into the port at Koh Sdach, a sparse depot for fishers and tourist boat drivers at the end of Union Road, which cuts diagonally down the Botum Sakor National Park. But many of the paved streets and dirt paths snaking off from Union Road are cut off by control shacks with barriers of chain-linked fences and corrugated metal. A drink vendor at the Koh Sdach port says their shops are also owned by UDG, and parked near his shop is an ambulance announcing itself as a donation from UDG.

Among the buildings that UDG has constructed are dozens of boxy wooden homes along Union Road, filling the spaces between construction material stores, drink shops and restaurants. The wooden houses overlook the patches of lake, forest and new clearings at the edge of a valley, where the sun’s heady rays turn the view golden by the late afternoon.

That beautiful land is not fertile, and the houses have worn out quickly in Koh Kong’s weather, says Chao Sob, a 62-year-old, who still lives in a resettlement home he was given in the late 2000s.

Sob was a soldier since he was 17 years old, eventually joining Vietnamese forces to fight off the last of the Khmer Rouge. After he retired in the late 2000s, he says, Kun Kim, a general in the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, helped him receive the house and about 2 hectares of land, and he was grateful. However, the house is already getting old, he is struggling to survive on around 10,000 riel per day he makes from fishing, and he can hardly farm the land. He receives no help from the state since he received the house and some compensation, he says.

“Look at my house. Why do you keep me from getting IDPoor?”

Within a few years, most of his neighbors who received a UDG resettlement home had sold the property, saying Phnom Penh elites bought the land, even though it is on state land only leased as a concession to UDG.

Most of the sold houses stand empty and aging on the hillside. Sob too is aging, and he says he’s considered selling the house, but without family, it’s the last asset he still has.

“I will keep the land until I get a little older, then I can sell. If I sell now and spend it all, what will I have when I’m old?”

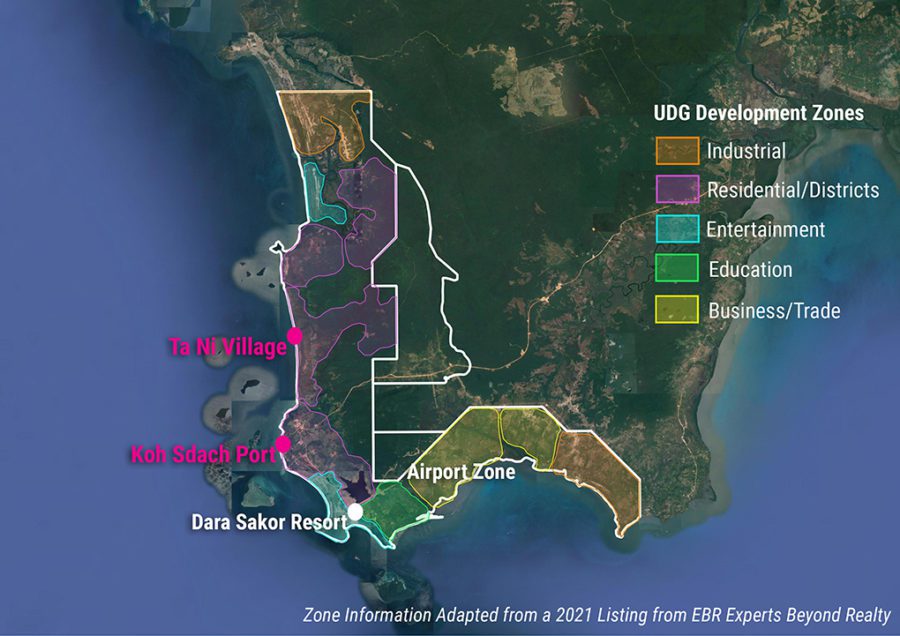

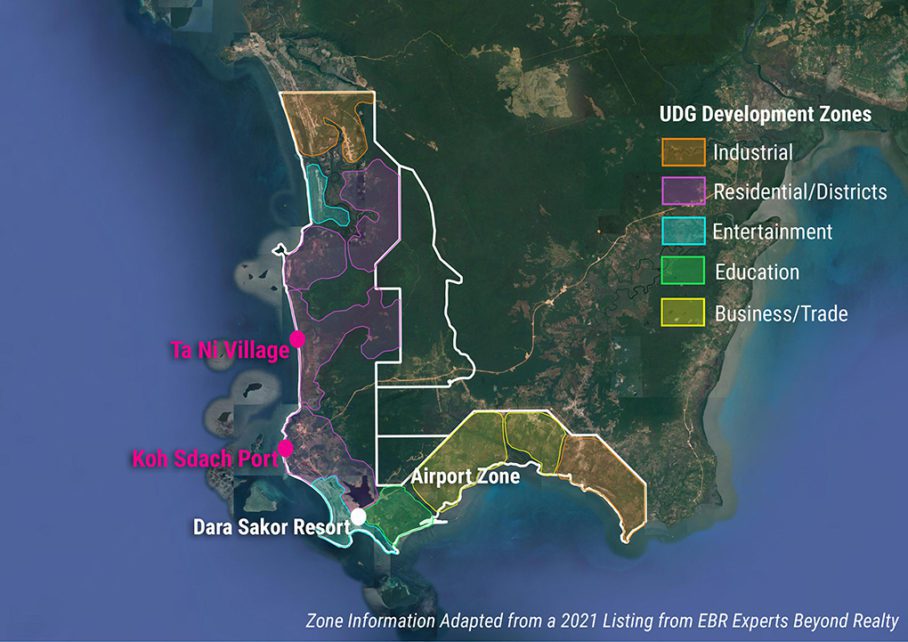

Sidebar: Development Zones

Though the Union Development Group could not be reached to explain the company’s development plans, real estate listings and its website suggest that a majority of the concession area is marked to build a new city.

Almost all of UDG’s largest concessions 一 36,000 hectares out of the total 45,100 一 will be used to develop a city with multiple zones, according to a listing from the Cambodian-based real estate firm EBR Experts Beyond Realty.

The larger concession is divided into 11 zones, including: the 3.2-km runway and surrounding airport and logistics zone; an education zone; a high-tech “innovation” industrial zone; a “wellness town”; entertainment areas; districts that include residential spaces; and an “elite zone.” However the post is sparse on details about what kind of businesses or features these zones would entail.

The real estate advertisement also advertises three areas on the market near the Dara Sakor Hotel, with prices ranging from $360 to $2,000 per square meter. According to CBRE data from the second quarter this year, an average affordable condo in Phnom Penh costs just under $1,500 per square meter, while high-end condos cost an average $2,800 per square meter.

UDG’s website offers a few more specifics on what the company plans to develop, suggesting it will develop at least two power plants, golf courses, an agro-industrial zone, marine food processing as well as helipads and yacht docks.

The Cambodia Constructors Association news website reported in July that UDG’s $350 million airport project is on track to start operations by the end of the year.

Note: This report was produced with support from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation under the financial support of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.