KAMPONG KBEUNG VILLAGE, Kratie — It’s 4:35 on the morning of January 8 in Cambodia’s northeastern province of Kratie. Twelve community fisheries patrollers have been mostly sleeping since 1 a.m., their bodies dotted around the embers of a fire on an islet in the Mekong River. Wrapped in blankets, the patrol team are exhausted after more than nine hours on the water.

Shouting suddenly shatters the tranquility. Within a minute, the whole camp is awake and on their feet. Two patrol boat engines sputter, then scream, and the fishery guardians tear off into the early morning darkness, chasing a bright light bobbing along the surface of the river somewhere in the distance.

“This is how they do it when they use electric fishing equipment,” says Sar Kouy, leader of the patrol team in Kampong Kbeung village, a small island in the Mekong near the border with Stung Treng province.

“Those lights you see, they use them to see how many fish they’ve stunned. They’ll be scooping them out of the water now,” Kouy adds.

Moments later, the roar of the patrol boats is joined by another sound. An engine starts up in the distance, and the light that was floating farther up the river goes out. For a while, all three engines roar, tearing through the water in a blind chase, but within 15 minutes, the patrol boats return to the camp on the islet, having lost sight and sound of the suspected illegal fishers and their boat.

As Kouy explains, illicit electric fishing is either “hot” or “cold”. “Hot electrocution” involves a low-powered battery joined with two iron rods by jumper cables, which stuns fish in shallow waters.

“Cold electrocution” is more destructive. It involves high-powered batteries, often taken from cars, being run through an inverter, which allows fishers to turn the electric field outward into the water. Electric fishers connect the battery and inverter to long, metal cables, which they drop deep into the Mekong, killing everything in the water up to 40 metres away.

Because of their impact on river ecosystems, the Cambodian government outlawed electric fishing kits in 2007. However, the law has not stopped those determined or desperate enough to use them.

“These days, we can’t keep up. Their boats are modified to be lighter and lower to the water with a fiberglass hull that glides along the water faster,” says 55-year-old Kouy. “It’s dangerous chasing them. We navigate in the dark because we know these waters — they’re our home — but we have to use light sparingly to avoid detection.”

Gunfights on the Mekong

Kouy’s all-volunteer patrol team is made up of residents of Kampong Kbeung — some in their early 20s, others in their 50s — most of whom are fishers themselves. In fact, almost everyone on the island fishes, either for subsistence or to earn a living.

But lower water levels, attributed to climate change and upstream dams, have made profiting from fishing more difficult. Paired with the pandemic economy cutting household incomes, more Cambodians were driven to engage in illegal fishing last year, advocates say.

The Wildlife Conservation Society warned that economic strain linked to the COVID-19 pandemic had pushed more Cambodians to turn to illegal poaching, and according to the Asian Development Bank Institute, 30 percent of households involved in farming or fishing have seen their incomes drop.

Armed only with flashlights and small boats whose paint is peeling, the patrollers spend a few nights each month on the Mekong, trying to protect the island’s fishing grounds from those who would resort to criminal fishing.

Kouy says he has been with the Kampong Kbeung patrol team since its founding in 2011, and has survived numerous altercations with illegal fishers on both water and land.

“Often, the illegal fishers are violent,” he says. “If they’re operating at this time, they’re likely armed and ready to protect their catch, so we’d need support from the police or even the park rangers, depending on where we are.”

While there is no violence on the waters surrounding Kampong Kbeung in early January, the economic desperation driving illegal fishing continues to result in confrontations with authorities in other parts of the country. Later that month, an illegal fisherman in Takeo province died after allegedly being beaten by government fisheries officers.

When illegal fishing reached a peak in 2017, Kouy says his team once broke protocol and rammed a boat suspected of engaging in illegal fishing. Both boats sank, and a fistfight broke out once the patrol team and the fishermen reached shore. He says the fishermen were arrested shortly after the fight. Kouy says he could not stand by and watch people destroy his community’s fisheries.

Around the same period, small armadas of illegal fishing crews entered the village’s turf from upriver. Eight boats fished in protected areas, while another two boats stood guard with guns and grenades. Kouy laughs as recalls the times his team brought slingshots to gunfights on the Mekong.

“Most of the time, it was just homemade guns, but these bigger operations were more heavily armed,” he says. “Although we see less of them now, back then you could see lights all along the river.”

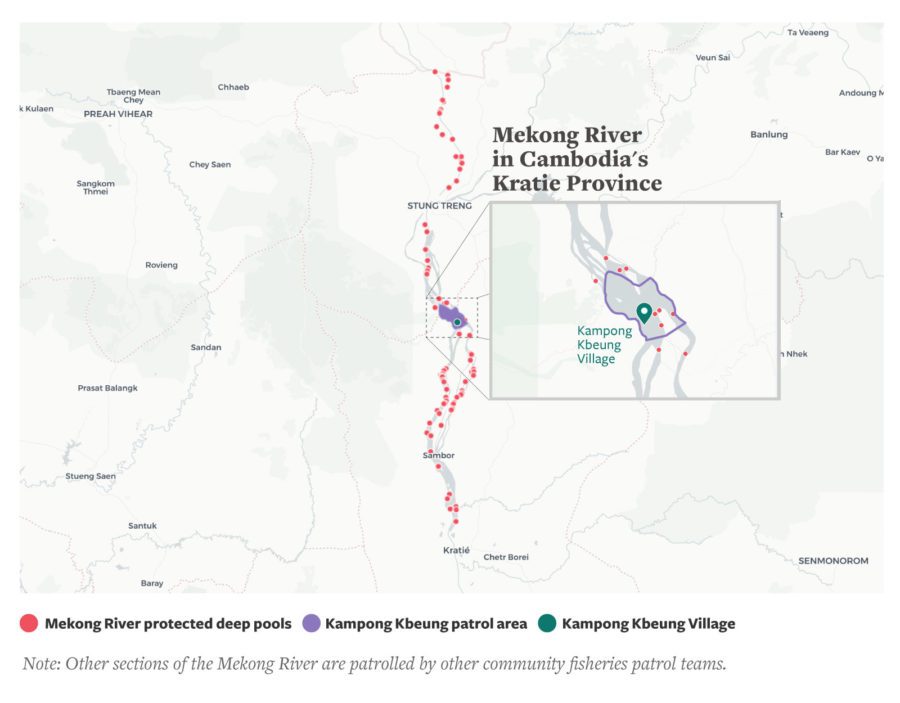

But this particular section of the Mekong remains notorious for illegal fishing due to the rich resources it boasts, according to Kouy. In Kratie province, some 62 protected deep-pool areas are home to fish hatcheries and nurseries.

Catches of rohu carp, hampala barb and four species of catfish — Kryptopterus, Hemibagrus, Arius and Pangasius — all native to the Mekong River, can be lucrative, but their breeding grounds make the area a target for electric fishers, which puts the livelihoods of nearby villages at risk.

“Lots of species have time to grow large here,” Kouy explains, noting that all deep pools along the Mekong in Kratie and Stung Treng provinces were designated by the government as protected since 1989, meaning any form of fishing within them is illegal.

After the brief excitement of the suspected illegal fishing boat sighting, the rest of the night patrol passes slowly and sleeplessly until 7 a.m., when the team return to Kampong Kbeung for a quick breakfast.

Despite being home to some 40 families, the isolated village has no operating school, no healthcare facilities and no semblance of local government. Even the village chief lives on another island.

There is no time for rest for the patrol team. They check in with their families to examine the legal catches that will shortly be bound for fish markets on the mainland.

A ‘Secretive’ Industry

Despite the prevalence of illegal activity on the Mekong, few on the island of Kampong Kbeung are able to explain how so much electric fishing continues to happen.

“We all know there’s electric fishing happening here … but I have no idea where they get the equipment. Nobody hears much because it’s all very secretive,” says fish trader Ouk Lang.

The morning after the night patrol, Lang has no fish to take to the mainland. Instead, he stays home and feeds his pigs and buffalos. He laments what he considers overly lenient punishments from the government’s Fisheries Administration when illegal fishers are caught.

“Nowadays, all we can do is patrol. We catch people once a month maybe, sometimes more, but they’re back on the water the next week,” Lang says.

The electric fishing equipment looks factory-made, he adds, guessing that there must be a seller somewhere in the area.

“People in the community say [the gear is] worth more than $1,000, but illegal fishers using it can make that back in under four days,” Lang says without elaborating on how he knows the supposed costs and earnings associated with electric fishing.

By 9 a.m., Kouy is leading a 15-man team with six boats back out on the water. Most have not slept since last night’s patrol.

“This electric fishing gear, it’s sophisticated. We don’t know where it’s bought, but it’s often left behind when someone we’re chasing abandons their boat, so we can see it’s not homemade. It’s very difficult and very expensive to wire it together,” Kouy yells over the sound of the engine as the boat cuts through the blue water.

“Everyone we catch with it says that it came from Vietnam, but that they bought it from someone who bought it from someone else who got it in Vietnam — it’s always middlemen. Nobody seems to know the source,” he adds.

Suddenly, the patrol boats swerve to a halt upon spotting nets that had been dropped in a protected deep pool. As the patrol team begins cutting the nets loose with pen knives, Kouy explains that the four protected areas in this small section of the Mekong are marked by concrete pillars. Neither that, nor the fines of up to 50 million riel ($12,500) and the potential three- to five-year prison sentences for using or transporting electric fishing gear, have stopped people from trying their luck in these breeding grounds, Kouy says.

The team hoists the nets out of the water and agrees to stake out a nearby islet to see if anyone returns to the protected area. Community fisheries, he explains, can work with the Fisheries Administration to establish fish conservation zones, or “no take zones”, where all fishing is illegal, but it is up to patrol teams like Kouy’s to actually protect them.

After an hour, with no sign of the nets’ owners, the patrol goes to meet with Sar Kim, the chief of Kampong Kbeung village. After greeting the patrol team with soft drinks, Kim dives under the bamboo stilts that hold up his house and comes wriggling back up with a 20-kg rice sack.

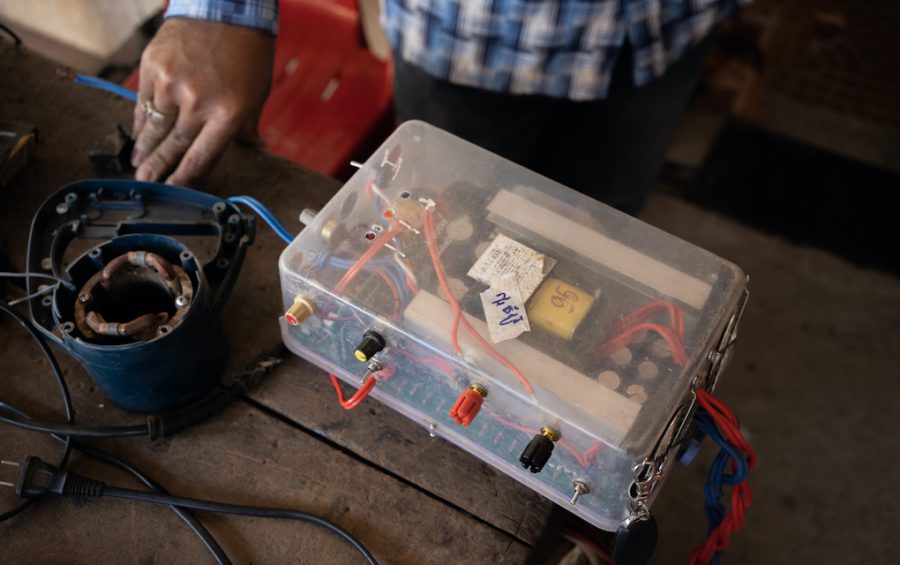

He pulls out a Chinese-made inverter — the key component of the electric fishing kit, which converts direct electrical current from batteries into the alternating current used to shock fish and everything else in the water.

“This is the only one we still have,” Kim says. “The people it belonged to left it in this sack when they ran. This is the expensive part.”

The village chief recalls a night patrol on 24 December, when the community team spotted fishers retrieving the sack from an uninhabited islet. They had stashed it there previously, but fled, leaving the inverter, when they saw the patrol boats.

“There’s really not much use for an inverter like this beyond electric fishing,” Kim says, suggesting it may have been bought at a hardware store on the mainland.

The rest of the day on patrol passes slowly, with few fishers out on the water at all. Around 3 p.m., the boats return to Kampong Kbeung, where the team finally get some sleep. But three hours later, they are finishing up their dinners, packing supplies and regrouping for another voyage into the night.

Exploiting Ethnic Tensions

The prevalence of ethnic Vietnamese people working within Cambodia’s fishing industry has often been a flashpoint for long-standing ethnic tensions and animosities, which opposition politicians have been keen to exploit.

As such, it is hard to determine whether the claims of fishermen and conservationists — that electric fishing gear is being brought into Cambodia by Vietnamese fish traders — represents an accurate reflection of reality or simply an expression of racial tensions. Almost everyone interviewed from Kampong Kbeung village said the electric equipment came from Vietnam, but none offered any proof.

Kampong Kbeung fisheries patrol leader Kouy mentions that electric fishing gear could be bought from Vietnamese traders, but adds that sellers of the equipment may have gone online to avoid the authorities.

In the town of Kratie, the provincial capital, a tuk-tuk driver directs reporters to a shop he says would know about electric fishing gear. The shop’s Khmer owner, speaking on the condition of anonymity, brings out what he calls a homemade electric fishing kit.

“You can’t buy inverters that powerful anymore, at least not openly,” the shop owner says. “It’s not that it’s illegal to sell them; it’s just that everyone knows that they’re used for illegal fishing. This one is homemade, a Vietnamese-Cambodian fisherman brought it to me to repair it. It’s not easy to make and definitely requires a level of technical expertise.”

He estimates that the “homemade” equipment sitting on his desk probably costs between $700 and $1,000 to put together. After showing him images of Sar Kim’s confiscated equipment, the shop owner says the bigger kits could be worth more than $2,000. These kits, he says, were probably being sold online.

When asked whether he would repair the electric fishing kit, knowing what it would be used for, the shop owner replies matter-of-factly: “Of course. I need the work.”

‘I Can Ship Them Anywhere’

A cursory search of YouTube found one channel, ostensibly run by “Tèo Nguyễn Văn”, dedicated to providing instructions on how to build electric fishing equipment. Listing telephone numbers and prices, the channel also appears to be operating as a sales platform. All 33 videos feature a Khmer-language speaker. The given Cambodian phone numbers were disconnected, and no new video has been posted for more than a year.

However, in the comments section of one video, another user — “Sarath Taxis” — inquires about the price and posts his phone number in the comments. Posing as potential buyers, reporters were able to gather more details about the origins of the electric fishing equipment.

“I couldn’t reach [Tèo Nguyễn văn] either, so I went to Vietnam myself last rainy season, around August, and brought a load of kits back,” says Sarath over the phone. “Different prices for different kits. The one in the video is $450, but I’ve got some Chinese ones for $150 and Cambodian ones for $100, so it depends on what you want to do with it.”

Sarath, who says he lives in Takeo province, explains that the Chinese and Cambodian models were only to be used in shallow waters and were consistent with descriptions of “hot electrocution” equipment. The Vietnamese model, he says, could be used for deep waters. The most expensive model sells for $1,000.

Later, Sarath brags that he never had trouble with the authorities — the equipment was dropped off at the Vietnamese border, where he slipped through and retrieved the packages.

“It’ll take about a week to get it to you, but I can ship them anywhere in Cambodia — any province you like. I just put them on buses, nobody knows what to look for, so it’s pretty safe,” he says, before adding that he would only send the equipment after receiving payment upfront. “I only sell for extra income. I’m a taxi driver. I fish [with the electric equipment] sometimes, but usually [I only sell to] people I know — people I trust.”

‘Hard to Police’

The patrol team works unpaid to preserve their community’s livelihood, but they receive funds for boats, fuel and supplies from the Fisheries Administration and a range of NGOs. Kouy, who is once again at the helm of the night patrol, explains that resources remain limited.

“The main issue is petrol,” he says, as the team pulls up to another uninhabited islet. “Without enough fuel, we can’t engage in much of a chase, and we can’t just patrol on the water all night.”

Rather than high-octane pursuits up and down the pitch-black Mekong River, the team mostly sits, watching and waiting. The waiting eats up hours, with teams from other islands stationed at various deep pools along the river, depending on where illegal fishing boats have recently been spotted.

On the first night of patrolling, the team had tried to blend into the darkness. On the second, however, they change their tactics.

“We have eight teams posted across the water, spread far,” Kouy explains while members of his group joke around as they cook small fish on bamboo skewers over a roaring fire. “We want them to know we’re here because one of two things will happen: They will see us and run away scared, or they will think we’re also illegal fishers and try to join us, and then we can check their equipment.”

However, after the patrollers lay their trap next to a protected deep pool, the night unfolds slowly and without incident.

“From my perspective, the number of illegal fishing cases seems to be falling,” Kouy says, noting that his team usually confiscates one electric fishing kit each month. “There used to be so much more violence, so many more illegal boats, but we’re catching fewer each year. I don’t know, maybe they’re just getting more careful.”

In fact, illegal fishing incidents are rising, even while fewer perpetrators are caught, according to Son Sovann, director of Northeastern Rural Development, a local NGO that has developed a network of 27 community fishery patrol teams — including Kouy’s — across Kratie province.

“It’s hard to police though, the illegal fishing, because more often than not it’s people from within the communities that are involved. They won’t do it in their own villages,” he says.

Most community fishery teams only have the resources to patrol four to six times a month, Sovann adds.

“It’s a grave danger for Cambodia’s fish populations, especially with the low waters of 2020,” he adds. The Mekong River’s water levels in Phnom Penh dropped to just four metres in September 2020, less than half of the recorded average for that time of year.

Upstream dams have lowered water levels, depleted fish stocks and even altered soil composition, Sovann says.

“As a result, people can’t farm the land the way they used to, and now the Mekong’s water levels, the Tonle Sap’s reversal — they’re becoming unreliable, so it’s understandable that people are turning to illegal fishing, but it’s dangerous, and it’s damaging,” Sovann says.

Last year saw worrying delays to the natural annual reversal of the Tonle Sap River — a key stage of fish reproduction in the Tonle Sap Lake — leaving fishing communities adrift. Sovann worries that economic desperation will push more people to fish in protected areas. Noting the difficulty in quantifying the financial value of the illegal freshwater fishing industry, Sovann says he has been working to ensure fishing communities are aware of the long-term damage that such short-term gains can bring.

The profits of electric fishing vary wildly, depending on the location, the species caught and the frequency the fisher can take the illegal equipment into the water without being caught, Sovann says, estimating that electric fishers can make in excess of $1,000 per month if they are not caught.

He also hints at the suspected involvement of officials within the Fisheries Administration in illegal fishing operations. When community river guards team up with government fisheries officers, the patrols seem to catch fewer criminals, Sovann says.

“I hear reports from patrol teams of authorities being paid off by illegal fishers. We’ve had instances where the [community] patrols have been infiltrated; they learn the schedule of the patrols, the methods and the routes, and they just work around it. It’s gotten so bad we can’t publish our schedules to our stakeholders,” he says, adding that patrols have been generally more effective since they started withholding their schedules.

A Better Example

Despite local communities’ claims that illegal electric fishing remains a threat to their livelihoods, authorities insist that incidents are on the decline. According to Mok Punlok, deputy chief of the Fisheries Administration for Kratie province, authorities investigated just four cases of illegal fishing using electric shock devices in 2020. Two suspects were jailed, and their batteries, inverters, wires and boats were also seized.

Illegal fishing cases were down from seven in 2019, Punlok says.

Asked to elaborate on how a small number of investigations represents a decline in criminal activity, and whether he was aware that electric fishing equipment was being advertised on social media, Punlok declined to comment.

Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Veng Sakhon could not be reached for comment.

Meanwhile, criminal fishers’ ongoing assault on the livelihoods of fishing communities along the Mekong belies law enforcement statistics, leaving their fate hanging on the perpetrators’ consciences. According to one former electric fisher, more work needs to be done to educate these people.

In the village of Samphin, in Kratie’s Sambor district, Meas Yen spends a portion of his time supporting the local fisheries team, patrolling the waters for illegal fishers. But some 18 years ago, Yen was on the other side of the equation — evading boats similar to the ones he now mans.

“I didn’t think carefully about the impact it would have at the time,” Yen says. “I just saw so many of my neighbors and friends using electric equipment when fishing. They made so much money, maybe 1 million to 2 million riel [about $250 to $500] per month.”

“That was a lot for families in our area,” he adds.

In awe of the income, Yen set off to find a trader, who he says sourced the electric fishing equipment from Vietnam. He paid $100 for the kit and soon started using it along the Mekong.

However, as the years went by and electric fishing methods grew in popularity throughout Kratie, Yen says his community noticed a clear drop in both the volume and size of the fish caught. Everyone’s livelihoods were affected.

“I can’t remember when exactly, but the commune chief started a group for teaching, sharing information. It was clear to us then what we were doing, and why the [electric] gear was damaging. We learned that there were fines and even jail sentences for illegal fishing,” he says. “If I go to jail, who will feed my family? I decided to stop since around 2003.”

Today, Yen mostly farms rice and cashews, and he joins his village neighbors on regular fishery patrols, aspiring to be a better example.

“I hope that I can be a role model for people in the community to give up illegal electric fishing and protect the environment,” he says.

This article was produced by New Naratif and VOD, who have partnered to publish long-form journalism from Cambodia that empowers our shared community with news and information.