Imagine a city where the elderly can travel unassisted to a local shop, where a person with a visual impairment can easily travel across the city to visit a friend, where a pregnant person can commute for regular check-ups without difficulty, where children can travel to school and back home without worry, and where even the most disadvantaged person can affordably commute for fair employment.

Ses Aronsakda is a junior researcher at Future Forum. Educated as an architect, he conducts research on Phnom Penh’s urban planning with interests in all aspects of cities and urban design.

Ses Aronsakda is a junior researcher at Future Forum. Educated as an architect, he conducts research on Phnom Penh’s urban planning with interests in all aspects of cities and urban design.

In such a city, mobility is equitable for all citizens, regardless of their mental or physical capability, their gender, their socioeconomic status or their age.

For Cambodians, at present, fully equitable mobility is not the reality. This is because the country’s towns and cities are heavily dependent on, and are built around, private vehicles.

Automobiles and Motorcycles Are the Least Inclusive Option

In a city designed around the use of cars and motorcycles, not being able to drive means not being able to get around independently. When a city is only inclusive for motorists, then non-drivers are equivalent to second-class citizens.

In order to qualify to drive a car, motorists must be over 18 years old, pass a driving test, be physically and mentally fit, and possess good vision. Although there is no driving test needed for a motorcycle and age is less restricted, one still needs to be in good physical and mental form to brave chaotic traffic on a motorcycle.

These sensible requirements, however, exclude those with mental or physical disabilities, the elderly, children, those who don’t have access to or can’t afford to attend driving schools, those who can’t afford to buy and operate a car or a motorcycle, and many others.

Recent reforms have broadened driving eligibility to include some forms of physical disabilities and have allowed motorcycles modified for disability users to be legally registered.

Although encouraging, it only treats the symptom of inequitable infrastructure rather than the root cause. Not to mention it only places the burden of driving and the associated risks onto vulnerable individuals.

Apart from accessibility, there are other disadvantages in primarily relying on cars and motorcycles. Traffic accidents are the leading cause of death and injury among Cambodians, with motorcycle users being acutely at risk.

Lately, sharp increases in fuel prices have also underlined the economic cost of motor vehicles. Among Southeast Asian nations it has been estimated that ownership of a medium-sized sedan imposes an average annual cost (including fuel, maintenance and taxes) of $5,261, while the annual cost for a motor scooter is $353 as of 2020.

Currently, fuel price hikes have pushed that cost even higher for Cambodians. Thus with the cost of private transportation eating into meager incomes, it places a disproportionate financial burden onto lower income families.

From an equity-oriented perspective, a city designed around the use of private vehicles hampers the mobility of a sizable portion of its inhabitants, puts them at increased risk and saddles them with disproportionate financial strain. Therefore, it is obvious that private vehicles are not the basis of an accessible, safe and affordable transportation system.

Prioritizing Active Commuting and Public Transit

In contrast to a vehicle-centric city, a city which is designed around active commuting — biking and walking — and public transit is better at providing equitable mobility for all of its citizens.

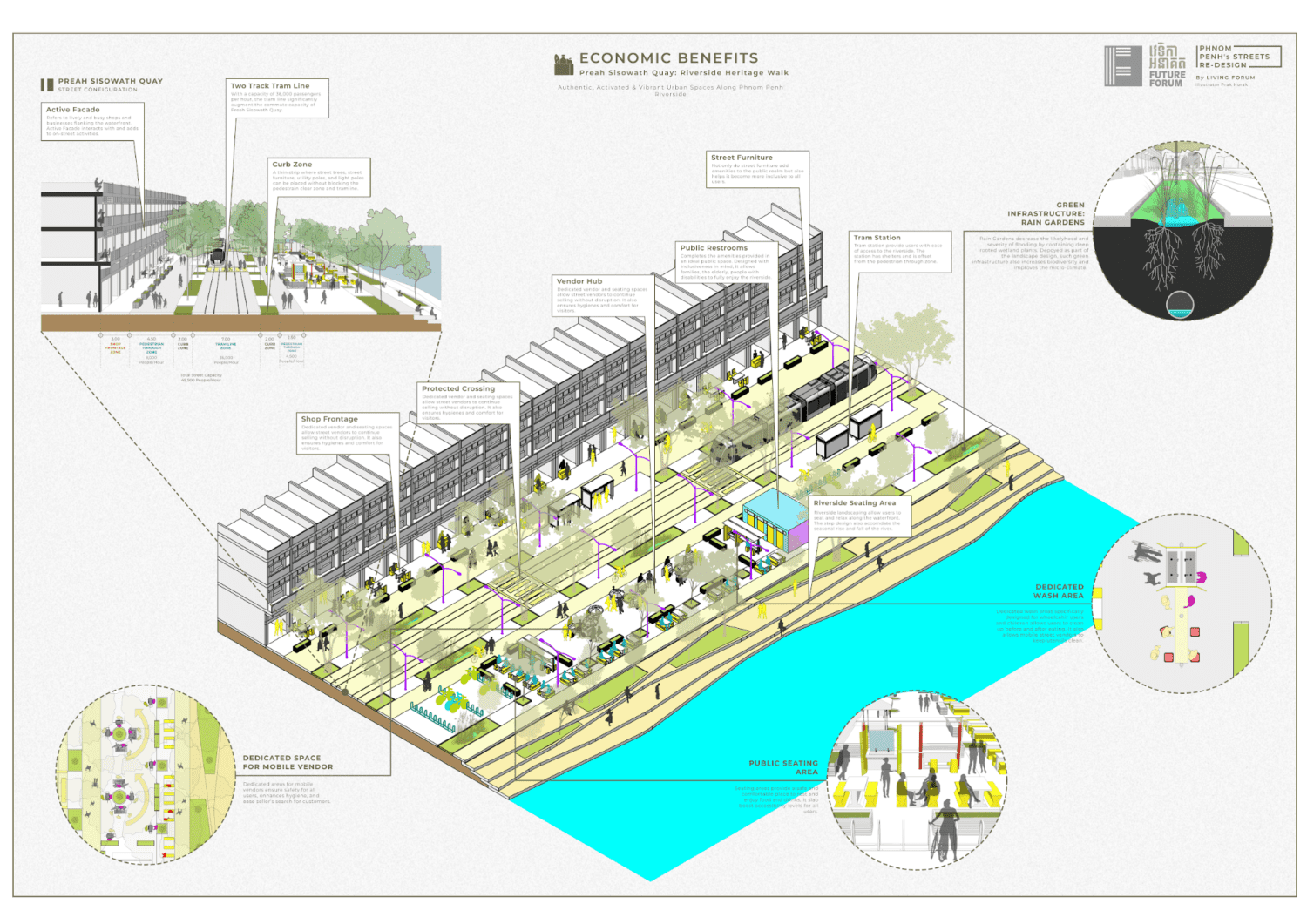

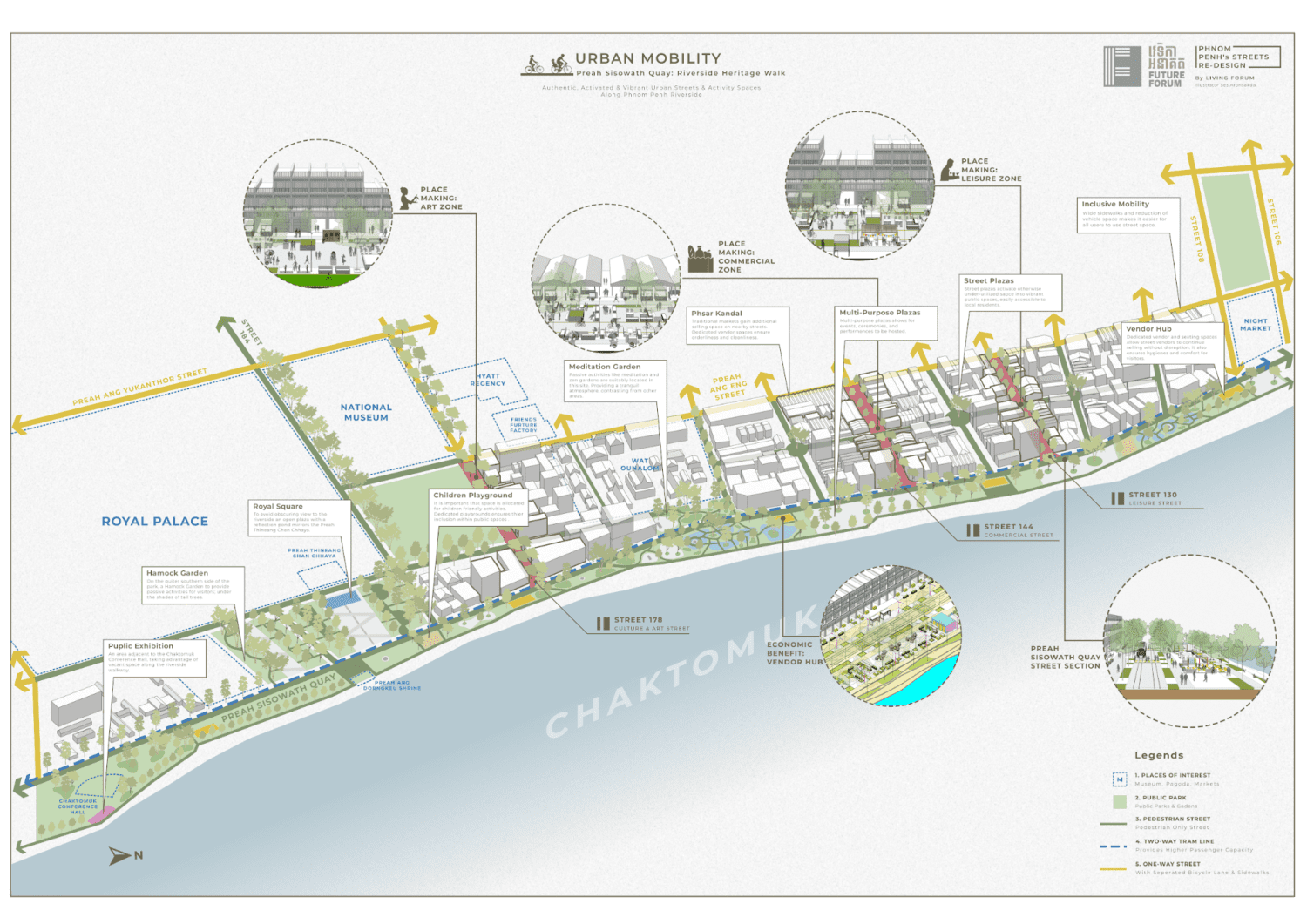

First, designing urban areas around walkability and bikeability has many tangible benefits. Walking and cycling — the most basic forms of travel — are virtually free, so those who can’t afford private motor transport can safely, conveniently and affordably commute. Moreover, well-designed pedestrian and cycling infrastructure also allows people with disabilities, who rely on mobility devices or tactile surfaces, to safely navigate the city unassisted.

For more distant commuting public transportation is paramount. Likewise, it is space- and cost-efficient, as well as being sustainable and accommodating for citizens with disabilities.

Neighborhoods and districts planned around public transit stations offer inhabitants unparalleled access to the rest of the city, while being cost efficient to construct and operate relative to vehicle-centric infrastructure. These factors ultimately make public transit more affordable to citizens, opening the possibility of regular commute to even the most disadvantaged communities.

Additionally, public transit systems can be much more easily modified to accommodate for disabilities compared to smaller private vehicles. Buses can be equipped with wheelchair lifts to allow mobility device users to board safely, while transit stations can be designed with lifts and ramps to enhance accessibility.

Walkable and bikeable streets in combination with robust public transportation offers equitable mobility for both short and long distance commute. Individuals with disabilities, children, teenagers, women, minority groups and low-income families can enjoy better access to employment opportunities, housing, health care and other crucial services when these features are in place.

Beyond Equitable Mobility

The impacts of equitable mobility also go beyond the obvious tangible benefits. Less concrete factors, like inclusion, trust and belonging in a community, are also enhanced in a walkable and transit-oriented city.

Meaningful interactions are virtually impossible when people are zipping about in their own portable private spaces, i.e. cars and motorcycles. Think about the experience of meeting friends, neighbors or strangers on a sidewalk. Now compare that with the feeling of driving past each other.

This problem is further compounded by desolate streetscapes that are the result of private vehicle dependency. The resulting landscape has a negative impact on the sense of belonging in towns and cities, further reinforcing the stratification of Cambodian society.

In contrast, when more space is dedicated to people and activities, the quality of the public realm improves. This is because it opens up the chance for social interactions, commercial activities, leisure and recreation. More interpersonal interactions and connections foster a deeper sense of sharing such spaces, of belonging to them and of building a community around them.

Trust and safety also becomes a concern where vehicle-centric roads become clogged with traffic during rush hour, but far too devoid of human presence when traffic passes.

This is not how urban spaces feel when people are able to mingle about. Lively streets with constant foot and cycling traffic, activated by shops, parklets and small plazas exude a friendly and welcoming atmosphere. This is because spaces with active human presence are perceived as being safer and the residents there more trusting, due to the number of fellow citizens nearby.

A sense of belonging and trust is achieved through these small but decisive differences. They are what distinguish people-centered environments from vehicle-centered ones.

Due the absence of these factors in urban areas, many Cambodian urbanites yearn for the connectivity of rural villages. Perhaps what is keeping us apart may not be the concrete and steel, but our motor vehicles and the desolate spaces they encourage.

What Cambodian Cities Are Missing

Equitable mobility allows a city’s inhabitants to travel inclusively, affordably and safely. A commitment to public transit and active commute ensures that residents of various ages, genders, capabilities, and socio-economic statuses all have the opportunity to gain the benefits cities have to offer.

Additionally, walkable and bikeable urban environments contribute to building social connections, engendering a sense of belonging to a community.

Equitable mobility is a crucial ingredient to creating a cohesive society. A city which achieves equitable mobility not only gives its residents a fair chance, but it is also a city that brings people together.

Ses Aronsakda is a junior researcher at Future Forum. Educated as an architect, he conducts research on Phnom Penh’s urban planning with interests in all aspects of cities and urban design.