Ses Aronsakda is a junior researcher at Future Forum. Educated as an architect, he conducts research on Phnom Penh’s urban planning with interests in all aspects of cities and urban design.

Ses Aronsakda is a junior researcher at Future Forum. Educated as an architect, he conducts research on Phnom Penh’s urban planning with interests in all aspects of cities and urban design.

The end of 2020 saw more private vehicles in Phnom Penh than people: a total of 2.53 million private passenger cars and motorcycles compared to its 2.18 million population. With about one car and four motorcycles for every household, this is a clear indicator that Phnom Penh is heavily dependent on private vehicles.

As Future Forum’s urban policy researcher, I spent the past year examining Phnom Penh’s urban mobility. A part of that study involved digging into Cambodia’s current parking policy and the impact it has on the city.

According to my estimation, the parking area required for all private vehicles in Phnom Penh is 22.8 square kilometers, which is roughly the size of Russey Keo district. But currently the city has only 0.98 square kilometres of registered parking space, which is severely inadequate.

Building a parking lot the size of Russey Keo district is obviously not possible. But even putting aside the logistical and financial constraints, adding more parking to a city isn’t a cure-all. In fact, too much parking can lead to just as many problems.

A Minimum Parking Requirement Is Not the Solution

Although an overlooked topic, parking policy significantly impacts urban mobility, affordability, growth and the environment of a city. Despite being such a multifaceted topic, current efforts of the Cambodian government focus solely on gaining more parking space for cars.

In 2015, the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction devised and adopted a minimum parking mandate. In this scheme, for example, restaurants and cafes are required to have one car parking spot for every 20 square meters of retail space.

This seems like a reasonable solution. But in practice, it subjugates the city to the needs of cars rather than the needs of people, and there are hidden costs to this decision as well.

The economic cost of a minimum parking requirement is severe, making construction and operation of property more expensive. The average cost of building a single ground-level parking spot is $500 as the cheapest option without even counting the cost of land, which would be exorbitant in Phnom Penh’s core.

For large retailers, spending millions of dollars to provide enough parking is not overly detrimental. But for small and medium-sized businesses, even a modest size parking lot may prove untenable, thus serving only to stifle growth.

More nefariously, minimum parking requirements also harm home buyers, as money spent on building the appropriate parking will be pushed back on to buyers as a hidden cost within the property price.

Lastly, there are also environmental costs to parking lots. They are impermeable surfaces and their concrete or asphalt construction — which in itself is an environmental concern — contributes to heat gain in urban areas, prevents the infiltration of groundwater and makes flooding run-off worse.

As a result, with a portion of any investment absorbed by parking, the city cannot build more affordable housing nor boost small shops and business, and is racked by the environmental impacts of parking structures.

Yet this is not all. As a whole, traffic in Phnom Penh will become worse if parking becomes more widespread.

An Oversupply of Parking Will Hurt Urban Mobility

Not only does an oversupply of parking occupy valuable urban space, it also causes further vehicle dependency, which ironically makes traffic worse. This is because with an abundance of parking, commuters gain a perception that it is always easier to drive.

Phnom Penh‘s Sen Sok district perfectly encapsulates this phenomenon, where the construction of large big-box commercial centers like, Makro, Aeon 2, Global House, Design Village and such all contain large swaths of parking space. Traffic congestion is a common occurrence in this area despite larger roads criss-crossing the district.

Additionally, parking lots lining the streets dissuade active commuters. The absence of buildings closely flanking streets, providing shade and a sense of enclosure creates desolate and uncomfortable thoroughfares for pedestrians and cyclists to navigate. With active commuting no longer an option, public transit also fails, which leaves only one choice — even more drivers on congested roads.

An oversupply of parking encourages vehicle usage, displaces other commuters and induces traffic congestion, which — taken as a whole — ultimately degrades urban mobility.

Solution Lies in Responsiveness and Adaptability

In light of this realization, instead of mandating minimum parking, city planners globally are moving toward systems which regulate the maximum amount of parking a property can have.

For example, in Portland, Oregon a parking maximum ordinance was enacted. Each category of building is given a formula to determine the parking minimum as well as the parking maximum. In some cases, the minimum and maximum lot requirements are reduced if a development is located close to a public transit system.

Vancouver chose to implement parking maximums as well, but went a step further in recognizing the reduced needs of parking in dense urban areas. Thus the city mandated a total parking cap in the downtown areas to prevent parking induced traffic congestion.

The city of Mainz, Germany gives a significant parking requirement reduction to properties that are in walking proximity to a bus station or tram station, the city even takes into account how well-serviced by trams and buses those stations are. This is to incentivize public transit usage and discourage vehicle usage in areas already well served by public transit.

Meanwhile in Singapore, the Range-Based Parking Provision Standards are based on urban density and proximity to public transportation. For example, Zone 1 (City Center and Marina Bay area) offers developers the freedom to reduce parking to only 50 percent of the minimum standard and capping maximum parking to 20 percent above the minimum standard, while other areas have their maximum parking capped at the previous minimum standard.

And these efforts can make a difference. A study on how the availability of parking impacts driving behavior illustrates a significant association between free and generous parking and the choice of driving a car to work — with the odds of driving quadrupling in this case. It also showed that no parking availability at work reduces the odds of driving most effectively.

Cambodia’s Case

In this regard, Cambodia is a step behind. As mentioned above, the country clings to a conventionally fixed parking requirement ratio. More importantly, it does not distinguish between property in dense urban zones and property located in the suburbs.

The way forward for parking policy is a more responsive and adaptable system. In this regard Phnom Penh can be bold and innovative by not just replacing parking minimums with maximums, but by formulating a context-based, multi-tiered parking requirement system.

This tiered system should be designed to take into account a number of characteristics like mobility access (is the location best served by public transit, active commuting or motorcycles?), utilization of space (does the space need frequent freight vehicle access?), centrality of location, urban density, existing street network capacity and related concepts.

It will then be possible to tailor parking requirements according to the local context. The densest parts of Phnom Penh with well-connected street networks should require the least amount of parking, which will make the areas less vehicle-dependent and encourage active commuting.

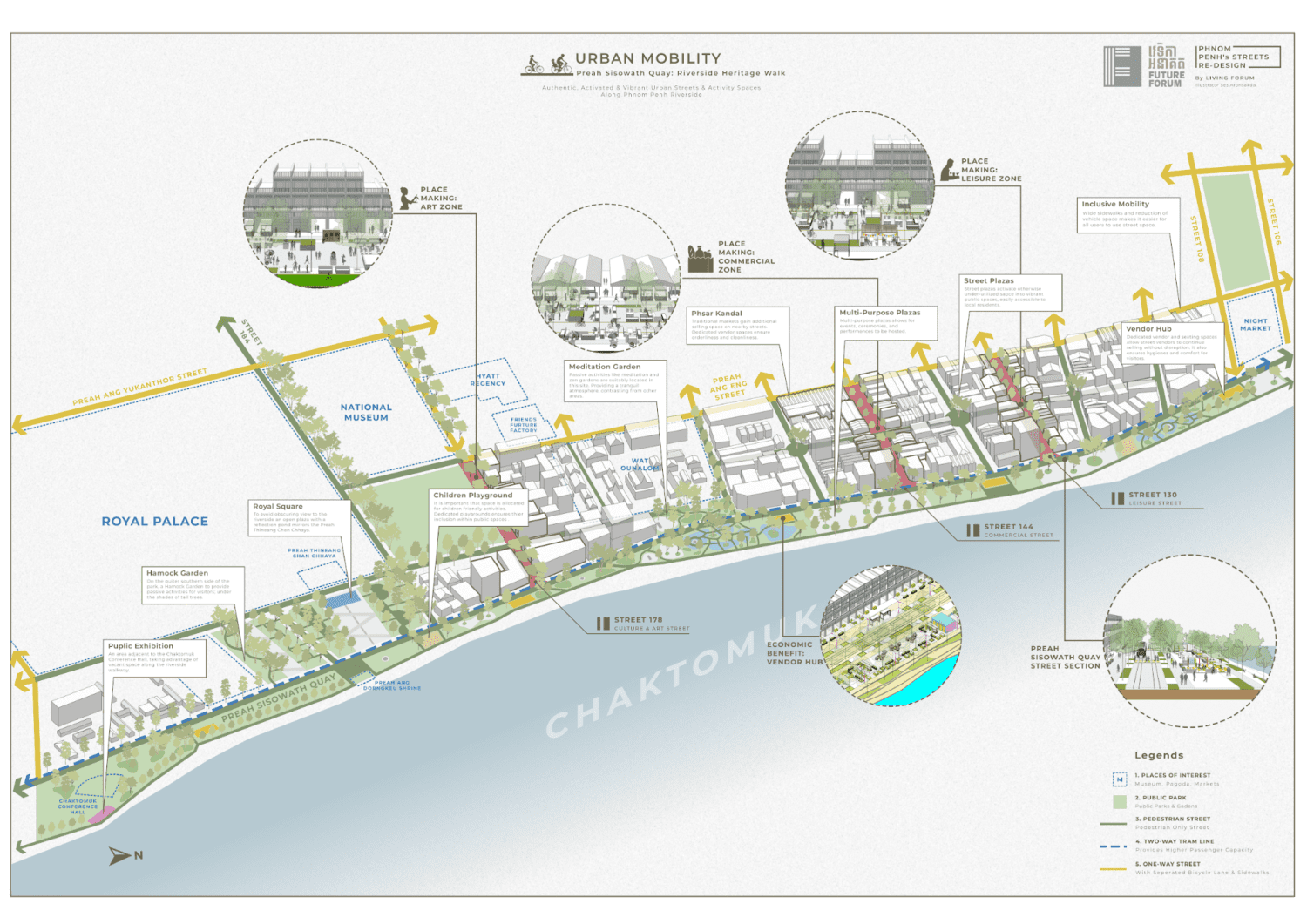

Dense areas with heavy commercial activities, like Phnom Penh’s traditional markets O’Russei and Toul Tompong, should introduce total parking caps to dissuade visitors from relying on private vehicles, while still preserving enough spaces for freight vehicles.

Reducing traffic congestion through curtailing parking space will also boost public transit speed and efficiency, making it a more viable alternative to driving. Thus, locations close to public transit should require even less parking to encourage public transit usage, particularly if this is combined with additional improvements to Phnom Penh’s public transit system.

For example, Phsar Thmey is the nexus of several bus lines, spanning all the way to its outskirts. But on-street parking around the market slows traffic and encourages visitors to drive there, thus negatively impacting the effectiveness of the buses.

Given its context, Phsar Thmey will benefit from eliminating on-street parking and using the space gained for bus shelters and pedestrian paths, boosting public transit effectiveness, gaining more space for visitors, and reducing congestion in its vicinity.

Meanwhile, Phnom Penh’s residential suburbs should retain minimum parking requirements to ensure enough parking for neighborhoods that are not covered by public transit. This is crucial for less fortunate residents who have no commuting alternative. It is, however, still possible to simultaneously impose maximums to curb overabundance of parking which is common in more affluent neighborhoods.

Likewise, suburban commercial streets should enact parking caps, and fee schemes for on-street parking to reduce reliance on private vehicles and to encourage the city’s development in a more sustainable direction.

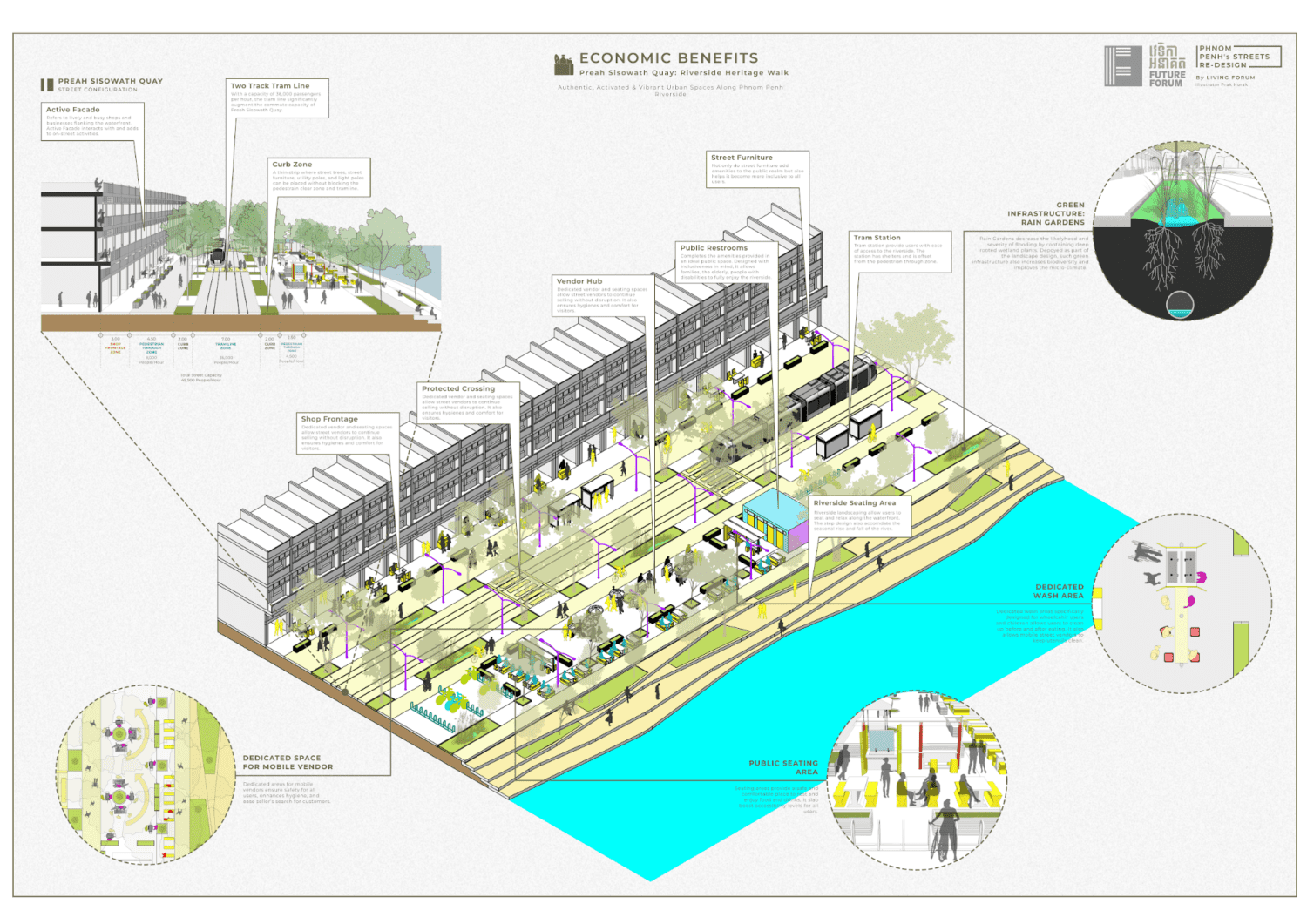

Furthermore, to avoid creating a desolate streetscape for pedestrians and cyclists, parking lots above a certain size should not be placed between the street and a building. Instead the building should be brought forward as close as possible to the street — while still respecting site setbacks — and the parking lots be placed behind the building.

A Human-Centric City

Parking policy is often overshadowed by public transit, urban parks or affordable housing discussions, but it is just as crucial in progressing toward a sustainable and livable city. Only through thinking beyond conventional rationale can Cambodian cities avoid the calamitous cost of outdated parking concepts.

More importantly, this is a chance for Phnom Penh and other Cambodian cities to be bold and innovative, replacing its vehicle-centric approach with a human-centric one.

Ses Aronsakda is a junior researcher at Future Forum. Educated as an architect, he conducts research on Phnom Penh’s urban planning with interests in all aspects of cities and urban design.