Every lake in Phnom Penh has been damaged by development and its wetlands decimated, leading to severe flooding, loss of livelihoods and disappearance of fish species, a new report says.

“Phnom Penh’s lake and wetland areas are on the brink of elimination,” says the report, published by urban development NGO Sahmakum Teang Tnaut last week.

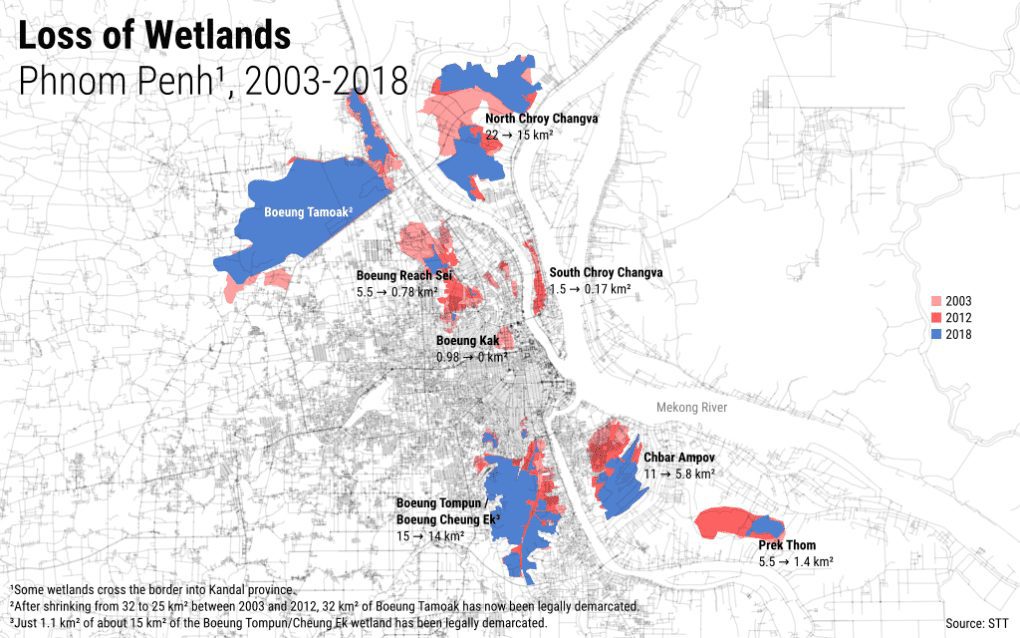

Titled “The Last Lakes,” the report examines the status of 26 lakes and 11 wetlands in the capital, and finds that 16 lakes — or 60 percent — have been completely filled in, with the remaining 10 all partially filled. By area, more than 40 percent of the city’s wetlands have been lost over the past 16 years, it says.

“Since 2003, developers of satellite cities and gated housing communities have poured sand into the wetlands and lakes,” it says. “Livelihoods based on the lakes and wetlands are being eroded, with thousands of families evicted or facing the threat of it as the development projects continue to threaten houses and jobs.”

The report, which looked at all major wetlands in the capital at least 0.5 square kilometers in size by examining satellite imagery, notes their key role in absorbing floodwaters in the capital.

“[P]redictions look dire, as flooding, environmental pollution and degradation of fishing breeding grounds is expected,” it says.

Boeung Reach Sei, in the north of the city, was filled to become the Grand Phnom Penh International satellite city, while Boeung Kak, near Wat Phnom, famously saw violent evictions as developer Shukaku filled in the lake starting in 2008.

On the Chroy Changvar peninsula, Orkide Villa was involved in partially filling in Boeung Kham Porng lake, the report says. Prime Minister Hun Sen’s daughters Hun Mana and Hun Maly are directors of some of the Orkide Villa companies, according to Commerce Ministry records.

Two major wetlands remain in the city — Boeung Tamoak, in the north, and Boeung Tompun, in the south. Boeung Tompun is currently in the process of being partially filled in to make way for the ING City development.

Fishers and morning glory farmers around the lake said the area was rapidly changing.

Mom Savann, 39, who has lived around Boeung Tompun for about 30 years, said it seemed that half of the area he normally fished and farmed had been filled in. He felt powerless to push back, he said.

“It’s hard to stop them from filling in the lake because the lake legally belongs to them, and even if we say something, I don’t think there is anyone who can help us,” Savann said. He added that there were also benefits to the development — notably, better roads — and he did not have many good memories of the area anyway. “I’ve mostly had a hard time living here,” Savann said.

Lorn Sinach, a 34-year-old vendor, said her family’s income depended on the vegetables she harvested from the lake.

“If the lake is completely filled in, it will affect my family and other people in the village through loss of jobs and income,” Sinach said. “It will be difficult to find other jobs.”

Meanwhile, the future of Boeung Tamoak is also unclear, the NGO report says, noting that there has been infilling to make way for a market, while land prices in the area rose 27 percent in the first half of the year. Some local families on the water’s edge have received eviction notices.

Nhean Chhoeurn, a 44-year-old fisherwoman, said rumors abounded that the lake was about to be filled in.

“I worry about the future of the only lake that is left that can help the people who live around it,” Chhoeurn said.

Sahmakum Teang Tnaut’s report recommends special protections for the two wetlands, Boeung Tompun and Boeung Tamoak, to prevent “severe deleterious effects for the country.”

City Hall spokesman Meth Measpheakdey, however, said the government was already balancing development with social and environmental impact.

Cambodia is a developing country and the government needs to allow development in certain areas, he said.

“This development must serve to benefit the people as a whole,” Measpheakdey said. “With all of our developments, we have already given thorough consideration: The development sites have infrastructure, there is a drainage system and a proper sewage line, for the sake of the people.”

Developers were also thinking about social and environmental impact, he said.

But Soeng Senkaruna, spokesman for rights group Adhoc, said too often developers gave consideration to people and the environment only after upsetting the community.

“Most of the time, the development projects are put in place and only if there is a clash, a solution will be subsequently found,” Senkaruna said. “It is not appropriate.”

Additional reporting by An Khema, Aun Sylong, Kang Tha, Keat Soriththeavy, Mom Sam Oeun and Toch Thina, who are part of the Newsroom Cambodia training program.

(Translated and edited from the original article on VOD Khmer)