“When people ask me what I want to change in the world, I tell them I want to change my community first,” says Phou Sreymai, a 17-year-old student who started leading classes for younger kids in Phnom Penh’s Stung Meanchey district in May, after schools across Cambodia were ordered to close in March to prevent the spread of Covid-19.

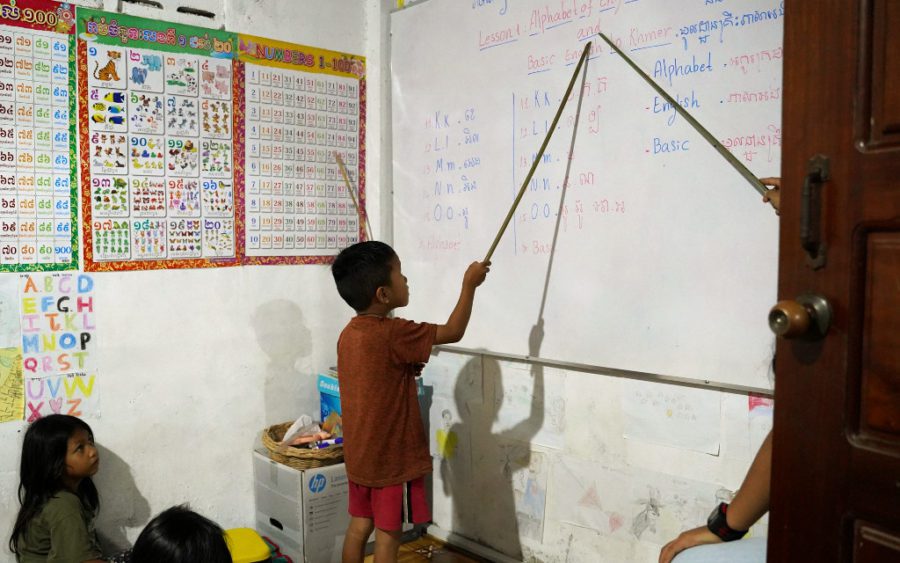

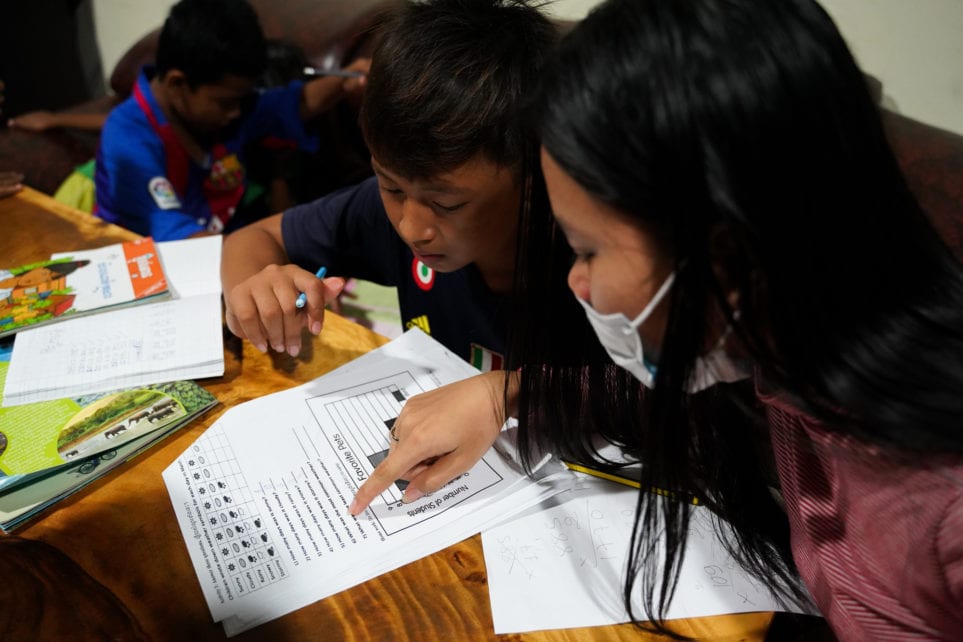

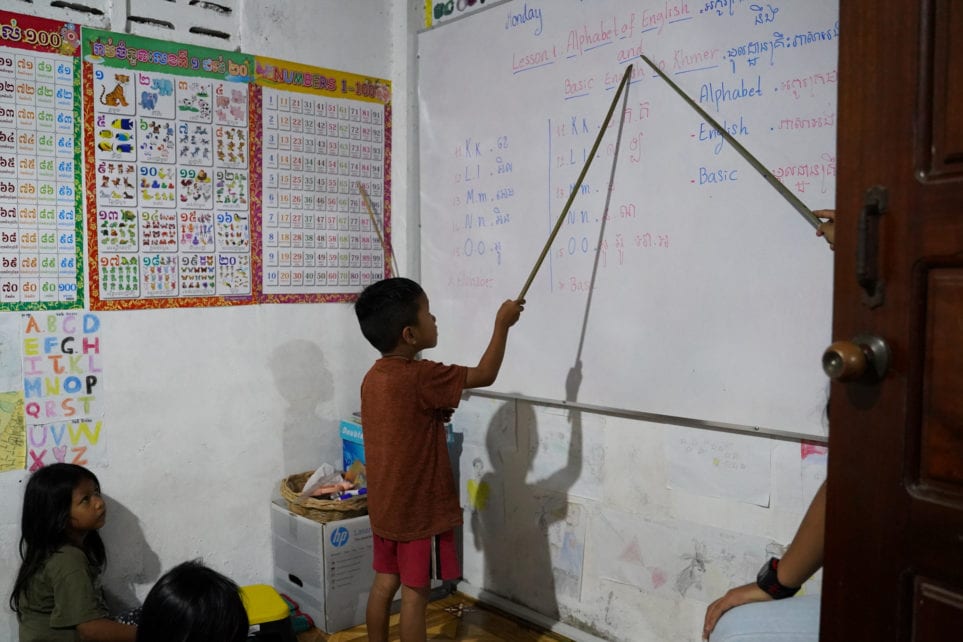

Together with a team of more than 100 students in her area, which is located next to a former garbage dump, Sreymai gathers dozens of younger children every day in makeshift classrooms set up under plastic tarpaulins and her neighbors’ homes.

Though students attending grades 1 to 6 and grade 9 and 12 in her area returned to classrooms in early September when the Cambodian government began the phased reopening of select schools, the young teachers are still teaching daily afternoon classes for younger children, some of whom remain out of school.

The young leaders’ efforts are partially supported by Cambodian Children’s Fund (CCF), an NGO that has been working with the Stung Meanchey community since 2004 and is providing the student teachers, who were initially unpaid volunteers, with modest stipends.

Sreymai hopes the free classes will encourage young kids to continue studying — rather than finding paid work — despite financially difficult times for their families. The children may feel like studying is useless in comparison to earning money, Sreymai adds, admitting that she felt similarly when she was their age. However, after seeing the sacrifices her family and aid workers made to keep her in school, and inspired by older students in her community who have gone on to university, Sreymai believes that the most important thing in her life is education. “I want to be the one who inspires others now,” she says.

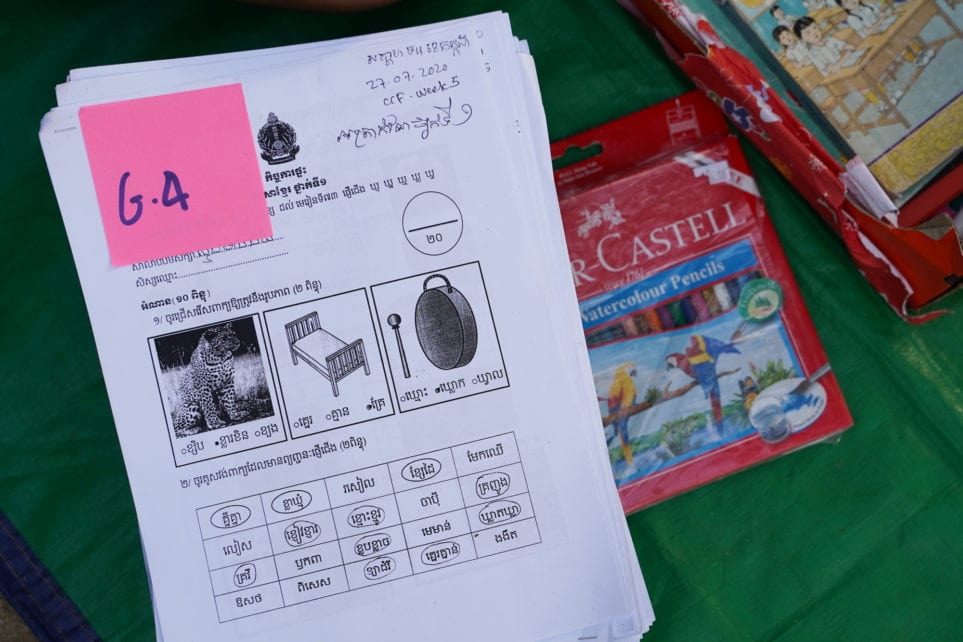

Though Cambodia has so far recorded fewer than 300 coronavirus cases, six months of closed schools risk long-term impacts on the country’s more than 3 million students, especially those in low-income communities that lack the resources necessary for distance learning. Students who cannot access government broadcasts of lecturing teachers and learning modules via social media, TV or radio must rely on weekly handouts collected from schools, which they often have to complete without much support at home.

According to Cambodia’s Education Ministry, protracted school closures risk increasing school dropout rates for children living in poor, marginalized communities. Before the pandemic, ministry data from 2017 to 2018 showed that some 17 percent of high school students dropped out before graduating, with the rate for students in rural areas slightly higher than in cities.

In rural Siem Reap province, 29-year-old Soth Bopha started the first Village Library in Nokor Thom commune’s Areak Svay village, after seeing kids “just playing cards or walking around the fields” when schools closed in March. Now in two locations in Nokor Thom and a third in another commune, her grassroots library project is run and supported entirely by volunteers, including the librarians who offer spaces in their own homes for children to read, play or attend free daily Khmer and English lessons.

Few students and teachers were observed wearing masks or social distancing at the libraries, or the Phnom Penh youth-led classes, but kids are taught how to wash their hands properly and a donor gave a hand-washing station to the Village Library in Areak Svay village.

The Areak Svay library recorded more than 500 book borrowings in August 2020, up from only 100 when the library first opened in May. But according to librarian Khat Da, some children stopped coming after they finished reading all the books that were available. The libraries are therefore considering rotating books between different locations.

“When I see children reading, I think it’s the happiest time in their childhood,” Bopha says. Since early September, primary school students in Siem Reap city have been back in the classroom for a few days a week on a rotational schedule.

But the libraries in Siem Reap remain open and students still come to borrow books and attend daily English classes, the librarians say. Bopha hopes that children can continue to have access to the experience of reading at the community libraries long after the pandemic subsides.

For more information about the Village Library project, and to find out how you can donate books and other resources, visit their Facebook page.

This article was produced by New Naratif and VOD, who have partnered to publish long-form journalism from Cambodia that empowers our shared community with news and information.

Correction: The article has been corrected to note that a donor, not volunteers, provided a hand-washing station to the Village Library in Areak Svay village.