CHHEB DISTRICT, PREAH VIHEAR — Thousands of indigenous Kuy people in Preah Vihear province are losing their livelihoods — with almost entire villages falling into debt — as five sugar plantations linked to one Chinese company have cleared an estimated 20,000 hectares of forests and locals’ farmland.

Based on interviews with 25 local residents as well as input from NGO researchers and an investigation of the area, VOD has found that five companies linked to Guangdong, China’s Hengfu International Sugar, skirted Cambodian laws and permits to amass economic land concessions four times larger in total than allowed for a single entity; razed forests before producing an environmental impact assessment, notifying villagers or compensating those affected; and cleared land too close to waterways.

Agriculture Minister Veng Sokhon acknowledged there were “some shortcomings” surrounding the sugarcane plantations. However, following several attempts to get a response from the company, a representative ultimately declined to comment on the record. She suggested the company faced challenges in navigating the issues raised but would not offer a public statement.

As Cambodia waits for a final decision from the European Union on whether the country will maintain duty-free trade preferences with the bloc — under review due to human rights concerns — a local rights group and E.U. documents say sugar concessions in Preah Vihear are among the entities being examined by the E.U. for alleged rights violations.

The E.U. has noted long-running concerns over the dispossession of families living or working on land that was later designated as economic land concessions (ELCs) and given to private companies for large-scale agricultural development, especially sugar plantations.

Inadequate to no compensation to displaced locals, and a small proportion of indigenous groups receiving collective land titles have also been highlighted by the E.U.

Residents of Preus Kaak village in Chheb district’s M’Lou Prey 2 commune estimated that 90 percent of the village was currently in debt.

“Before the companies’ arrival, we were able to hunt wild animals and sell them for petroleum, or liquid resin, dry resin, or orchids, or ginseng, or sticky rice,” said Iem Aon, 60, who lives in Preus Kaak.

“Now, we are not able to find them. So we are forced to borrow money,” Aon said.

“If there is a drought and we cannot grow rice, we will probably sell our property, for those who have it. It will be difficult for those who don’t have any property to sell,” Aon added.

Heng Phuon, the village chief of neighboring M’Lou Prey 1, in Chheb district’s M’Lou Prey 1 commune, said that in recent years, his people had effectively been forced to exchange land ownership for growing levels of debt.

“Before the Chinese companies’ arrival, people were not in debt to the [microfinance institutions] like today,” he said.

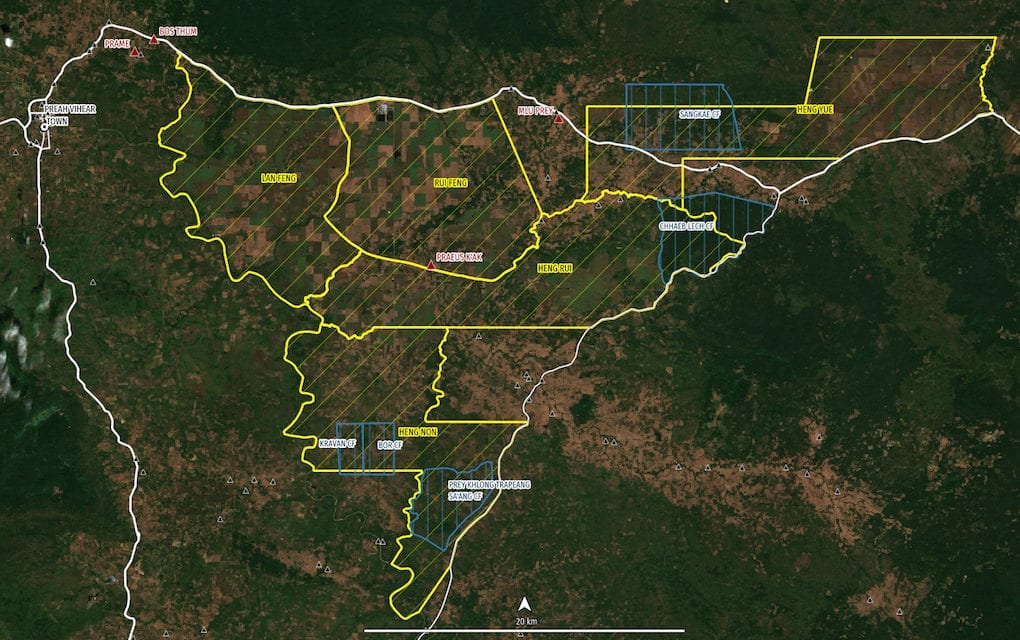

In 2011, the government granted five companies — Heng Nong, Heng Rui, Heng Yue, Lan Feng and Rui Feng — land concessions of between 6,488 and 9,119 hectares each, with three of the companies, Heng Nong, Heng Rui and Heng Yue, receiving contracts on the same day on November 8, according to NGO records of official decrees.

Together, the five companies received 42,422 contiguous hectares in Preah Vihear, records from Open Development Cambodia and rights group Licadho show.

Under Cambodia’s 2001 Land Law, ELCs are restricted to 10,000 hectares. But Hengfu director Liu Feng told the China Daily in 2016, without mentioning the five subsidiaries, that his company had been granted 42,422 hectares for its development plans. Feng added that the company hoped to expand to 180,000 hectares in the future.

All five subsidiaries share the same address and contact numbers, according to a 2014 article in the Phnom Penh Post.

Addresses listed on the Commerce Ministry’s online business directory for Heng Rui, Lan Feng and Rui Feng were the same: Prince Tower (formerly Phnom Penh Tower) on Monivong Blvd. in Phnom Penh.

Heng Nong was not listed in the directory, while Heng Yue’s address was in Preah Vihear’s Chheb district, where an NGO worker said that firm has a rice plantation.

A reporter visited a Hengfu factory located in Chheb’s M’Lou Prey 1 commune, which processes rice and sugarcane, in July. A security guard did not allow the reporter to enter to interview a company representative. Phone numbers found for the factory either did not connect or reached people who said they no longer worked for the company.

Land Loss

According to local residents, the clearing of land began almost immediately in 2011.

“They hadn’t informed us that they would plant sugarcane or that they would clear some areas of land. We tried to stop them when we saw the bulldozers,” said Khiev Kim, 66, of Prame village in Tbeng Meanchey district’s Prame commune.

Poek Sophorn, an officer at Ponlok Khmer, said 25 villages in 10 communes and three districts were heavily impacted by the clearing, with many families kicked off their plots to make way for the sugarcane plantations.

About half of the entire concession area had now been cleared, Sophorn said.

The land rights NGO estimated that only 25 percent of about 2,000 affected families — some 10,000 people — held official land titles, despite their claims of having lived on the land since 1980 — a situation common in rural areas, which puts poor villagers at a disadvantage in the case of disputes.

Despite recurring protests in relation to the Hengfu sugar plantations, many of the dispossessed locals have yet to receive any compensation, NGOs and residents said.

“[Some] have never received compensation,” Sophorn said.

Grain, the nonprofit, says some residents were compensated only after the company encircled their land with sugarcane, “leaving no access to the land.” Evictees received as little as $250 per hectare, it says.

“People also reported the company seizing some titled land without paying anything,” the nonprofit says, in a joint report with Ponlok Khmer and three other organizations.

According to the Land Law, the dispossession of people’s land is disallowed “unless it is in the public interest,” and only “after the payment of fair and just compensation in advance.”

In addition to a lack of compensation, the companies also failed to come up with policies around social and environmental impacts until long after the clearings began. By the time they produced their environmental impact assessment, prepared by the Green Environment Group in July 2016, the disputes were already underway for five years.

Agricultural projects of 10,000 hectares or more are required to submit an environmental impact assessment before their approval, according to a 1999 sub-decree, a requirement apparently skirted by the five-way division of Hengfu’s land concessions. Penalties for violators increase for repeat offenders, and those found to have caused danger to people, private or public property, or the environment or natural resources may face up to five years in prison under the Environmental Protection Law.

Environmental impact assessments from Rui Feng, Lan Feng and Heng Nong in 2016, which were seen by VOD, say the companies will need to clear villagers’ farmland to make way for sugarcane, and adds that residents should be compensated at a reasonable price accepted by them.

Residents contend that the company has not followed even these belatedly produced social and environmental policies.

Sith Savorn, a community representative of Prame, said residents continued to file complaints to various authorities to no effect.

“There’s still no compensation,” Savorn said. “Residents of the resin-producing community continue to ask me: How many times have we filed complaints? And why aren’t they aware?”

The impact assessment also stipulates that forests must be retained for at least 100 meters on both sides of waterways, a condition that has been violated by the company.

Preus Kaak village’s Aon said the plantations had cleared land to within 10 meters of rice-field dikes without leaving the required strip of forest, a situation that was clearly visible to reporters visiting the area.

Sokhon, the agriculture minister, acknowledged that the companies had violated the terms of their concessions on some occasions, including clearing land before fulfilling some requirements.

“The procedure is good, but there are some shortcomings. Sometimes it is cleared before time, so it causes negative impacts,” he said.

After many attempts to contact the company — including visiting a worksite in Preah Vihear, and phoning, messaging and emailing several listed and solicited numbers and addresses — a Hengfu spokeswoman invited reporters to meet at the company’s Phnom Penh office on the 15th floor of Prince Tower, on Monivong Blvd., in October.

Sao Ly, the spokeswoman, declined to provide a public response to any of the issues raised by the villagers and NGOs despite speaking for about 15 minutes on the topic.

Sugar Concessions — a ‘Long-Standing Concern’

In 2016, a Rui Feng representative told the Phnom Penh Post that its $360 million sugar mill would produce refined sugar — 2,000 tons per day — mostly for export to the E.U.

Now, the E.U. is considering suspending in whole or in part Cambodia’s trade preferences with the bloc, if the country is found to have failed to comply with international human rights treaties.

The E.U.’s “Everything But Arms” (EBA) trade scheme offers Cambodia and other developing nations duty-free and quota-free access to the European market on all imports except arms and ammunition.

The World Bank has estimated that a suspension of the EBA could cost the country up to $654 million in trade to the E.U. — Cambodia’s biggest export partner. The Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia also has warned of major job losses among the sector’s more than 1 million workers.

A decision on EBA withdrawal is due from the E.U. in February.

In its review of the country’s EBA compliance, the European Commission has noted that while Cambodia has made progress in terms of land dispute resolutions, “shortcomings still exist in the areas of land registration, titling provisions and the lack of appropriate and impartial review as well as addressing issue[s] regarding the rights of the indigenous population.”

“Further efforts are needed in order to establish an appropriate legal framework to ensure transparent and inclusive mechanisms for the resolution [of] land disputes,” the Commission said, according to a confidential document seen by VOD.

A European Commission spokeswoman in December declined to answer questions about whether the ELCs granted to the five companies were included in the Commission’s EBA review, saying in an email that “the process is ongoing, taking all necessary elements into account.”

“We would not be in a position at the current stage to give you more details of the elements under consideration,” she said.

E.U. Ambassador Carmen Moreno also declined to comment, saying in an emailed statement that the EBA procedure had not concluded and its findings were confidential under E.U. regulations.

However, in another document dated March 29, 2019 and seen by VOD, the European Commission notes that “significant numbers” of outstanding land dispute claims remain, especially in relation to sugar ELCs in Preah Vihear province.

The Commission says there is a “long-standing concern” over the dispossession of families living or working on land granted to private agricultural companies in the form of ELCs.

“In the specific case of sugar ELCs, large numbers of families were dispossessed and received inadequate or no compensation,” the Commission says. “Despite requests over a number of years by the EU, there was little action taken for a considerable period by the authorities towards a comprehensive solution.”

Am Sam Ath, monitoring manager for human rights organization Licadho, said companies in Preah Vihear and three other provinces were included in the European Commission’s EBA rights compliance review.

“There are Chinese companies such as Rui Feng, Lan Feng and others, which are also under EBA evaluation,” Sam Ath said, adding that E.U. officials had visited the sites of those companies in Preah Vihear.

“For this visit, European Union officials wanted to know more clearly, because economic land concessions are also included in the evaluation,” he added.

Licadho has participated in meetings concerning land concessions with E.U. officials and other local rights organizations, he said.

The Commission’s EBA review document from March also notes that the process of attaining collective land titles for indigenous communities, while possible, remains “complex, lengthy and expensive.”

Only about 5 percent of indigenous communities in Cambodia — just 24 of an estimated 455 groups — have received collective titles from the government as of mid-2018, according to a U.N. report cited by the Commission.

Lost Opportunities

On April 19, 2016, Prime Minister Hun Sen attended an opening ceremony for Rui Feng’s sugar-processing plant, according to The Cambodia Daily.

Hun Sen promised hundreds of jobs for locals at the time, saying they had the opportunity to grow and sell sugarcane to the company.

However, Thean Heng, chief of Prame commune, told VOD that none of his villagers had taken up the offer.

“The company wanted a deal like this, but our villagers declined. I speak neither for the company nor villagers, but our villagers don’t want to work for anyone,” he said.

Already by 2016, after five years of land disputes, locals were not in the mood to cooperate.

“We don’t want to work for them on our own land,” 65-year-old Nuon Mon, who claimed Rui Feng had taken a 0.9-hectare plot of her land, told the Daily on the day of the ceremony. “They are no use to us.”

Rather than provide a boost to their incomes, in practice the plantations have had the effect of reducing the livelihoods of the communities around them.

Indigenous Kuy villagers interviewed by VOD repeatedly raised the loss of their ability to produce resin from the forest, a key source of income for the community.

“I abandoned this work because the company cleared the forests that used to produce resin for the community,” said Pin Chey, a 40-year-old Kuy woman from Prame.

Sun Veasna, a resin broker living in Bos Thom village in Tbeng Meanchey district’s Prame commune, said that before 2012 he used to buy 1,500 to 1,800 liters of resin a day from locals, but now he could only obtain 150 to 300 liters.

“The decrease is because the trees have been cut down,” Veasna said.

According to Ponlok Khmer, a community resin-processing plant set up with the NGO’s help in Prame was shut down in 2016 amid the decline in available resin.

Between 2010 and 2016, the community’s income from forestry products plummeted, a report by the NGO says.

In December 2010, when the plant started processing resin, the community earned 27 million riel (about $6,750). By the time the plant was shut in June 2016, it was taking in revenues of less than half that amount — some 13 million riel (about $3,250) — according to an accounting document from the NGO.

Seng Set, living in Tbeng Meanchey district, said with the loss of forests and families’ farmland, the poorer members of the community now had to till common rice fields.

“They’re forced to farm and share their farmland together,” Set said.

Sophorn, from Ponlok Khmer, said forestry products had previously provided decent incomes for locals, including through the collecting of vines, leaves, resin and more.

They offered a safety net for when rice crops failed due to inconsistent rainfall and droughts, he said.

Now, there were few alternatives, with most villagers unable to keep livestock like chickens, ducks, pigs or cattle, he said.

“Why? Because they have no land on which to tend the animals.”

Additional reporting by Matt Surrusco

(Translated and edited from the original article on VOD Khmer)

Note: This report was produced with support from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation under the financial support of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.