The deadliest fire in Cambodia’s recent history has put fire safety in the spotlight at Phnom Penh developments.

At least 28 people were killed in a fire likely caused by electrical issues at Poipet’s Grand Diamond City Casino late last month. During the rescue and cleanup of the sprawling complex, victims and foreign response teams raised concerns about a lack of alarms and sprinklers as well as locking doors and stuck elevators.

The concerns extend beyond the Poipet casino, with fire inspectors noting that there are common fire-safety infractions across the country.

The Interior Ministry’s fire department provided reporters with a variety of regulations on fire safety, though none of them contained detailed requirements for buildings. An inspection company also would not share Cambodia’s fire code, but said it was more comprehensive than regional neighbors. A representative for the company added, however, that “many” failed the assessments and the results were not made public.

Chin Daluch, manager of valuation and advisory services at CBRE Cambodia, said that fire safety standards were a common concern among would-be building tenants both international and local.

“Based on our experience, all international companies require fire safety standards in their building or they wouldn’t even consider the building,” she said.

Local tenants also regularly asked about fire safety, though not universally. Daluch estimated about 80% of local tenants raised the question when looking for properties.

Cambodia first introduced a law on fire prevention and fighting in 2014, designating the Interior Ministry as the body primarily responsible for fires, firefighting and punishments. It also established “fire certificates,” which are required for high-risk buildings and last for two years at a time.

The actual process of inspections was only specified after 2018 in a series of decrees for new buildings and renovations; Daluch said inspection requirements remained unclear for older buildings.

Notably, these decrees outsourced official fire inspections in the country to a single private company, Cambodian Fairwinds Enterprises.

The company’s chair, Wang Kitman, is an oknha and recipient of the government’s monisaraphoan tnat moha sena title for social impact, and was made an adviser to National Assembly president Heng Samrin alongside 31 others in October 2018, and given a rank equivalent to secretary of state.

Cambodian Fairwinds’ director of compliance consulting departments, Andrew Wallace, would not share the forms used for inspections, but said the fire code was “considerably more comprehensive than many countries’ Fire Codes in the region, but obviously not yet as developed as NFPA, British Standards, etc.”

Instead, he provided a list of more than a dozen common infractions:

- Inadequate water supply.

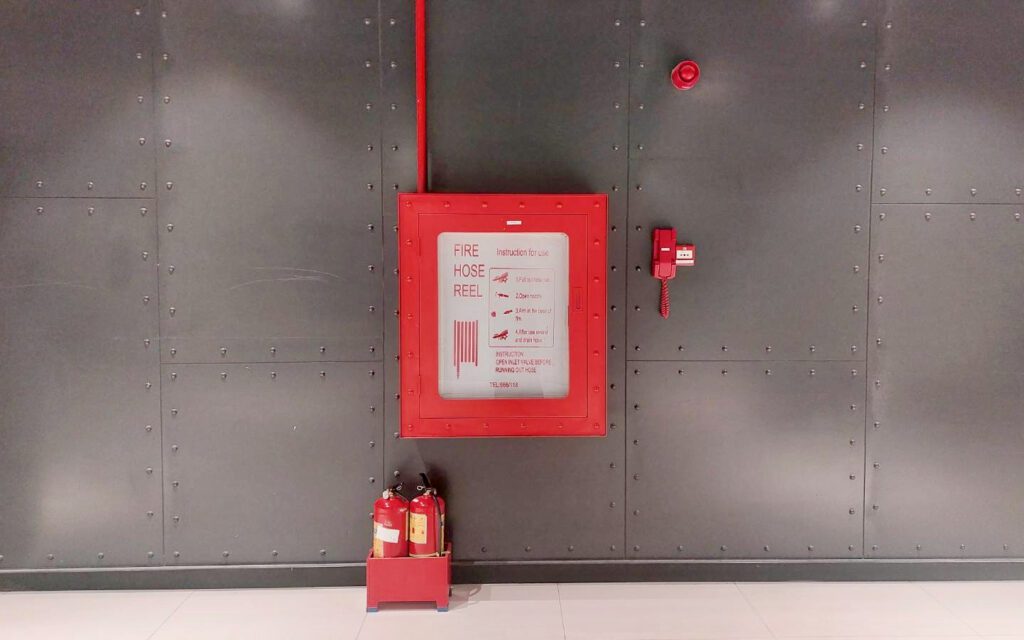

- Wrong and insufficient fire hose reels and fire hydrants.

- Poor access for fire trucks.

- Inadequate fire separation between buildings or within buildings.

- Lack of sprinkler systems.

- Lack of fire alarm panels and other extinguishing equipment.

- Wrong type of extinguishing equipment for particular fire risks.

- Inadequate and wrongly designed fire stairs, exits and doors.

- Wrong mix of building use sharing the same fire compartment.

- Badly trained personnel, without correct National Fire Academy of Cambodia certification.

- Lack of written fire safety plans or documented fire drills or maintenance records of fire safety equipment.

- Poor, insufficient or wrong exit signage.

- Inadequate or badly maintained emergency lighting.

- Poor, non-existent or badly designed smoke exhaust systems.

- Locked or blocked fire exits.

- Poor operational standards exacerbating the above failures.

Buildings and other locations considered high-risk for fire were required to apply for fire certificates from the Interior Ministry, after which Fairwinds employees conducted inspections, Wallace said.

Buildings needed to be inspected during design phases, before handovers from construction crews to operators, and every two years, he said.

He would not say how many inspections the company conducted, but added that “many” buildings failed inspections.

He said the results were not made public so owners could review and fix concerns.

The Interior Ministry’s fire department provided several documents on fire safety, but none that specified the exact standards for buildings’ fire-safety precautions. A June 2018 decree requires all buildings to have fire-exit maps and fire extinguishers by 2020, and outlines fines of up to $5,000 for repeat violators. A separate document says building owners must provide fire-safety clothes for a trained team who will be responsible in case of fire. A third says floor-plans must be kept at the police station, and lays out jail time for officials who fail to fulfill duties in a fire (six months to two years), people who obstruct firefighting (two to five years) and people who falsely declare fires (one to two years).

The Interior Ministry’s fire department director, Neth Vantha, could not be reached after several calls this week. Municipal fire department director Prom Yorn referred questions to municipal police deputy Sum Sokhim, who declined to comment. Three emergency phone numbers on the Fire Police and Rescue website did not connect.

Well-known buildings around Phnom Penh generally showed they had standard fire equipment such as extinguishers, alarms, hoses and other fire safety equipment when visited by reporters, though building management were reluctant to talk about precautionary measures.

The NagaWorld casino complex has fire extinguishers placed every 100 to 200 meters amid casino tables and slot machines and in the duty-free mall in its underground walkway. Nearby, the Bridge complex had fire hoses in glass boxes on the walls, and a few fire extinguishers placed next to construction debris in the nearly empty mall. Koh Pich property Morgan Tower displayed similar safety measures inside. Reporters were unable to receive comments from any of the properties.

Even when they don’t cause loss of life, the impacts of smaller fires can be felt for months after. In Toul Svay Prey I commune, where a blaze broke out among a wet market covered by a corrugated metal roof in mid-October, a woman’s clothing vendor who gave her name as Sy said she had lost nearly $10,000 worth of dresses she sells in the narrow market next to Phnom Penh’s Wat Moha Motrey primary school.

Sok Lin, 28, who owns a neighboring meat stall with her husband, said she too lost everything but a few knives in the fire, which burned for about two hours. Vendors said the response from firefighters was sluggish.

“I lost the most out of everyone here,” Lin said. “It impacted me a lot emotionally.”