Cambodia’s state electricity provider is pushing ahead with the construction of a transmission line through the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary, a plan that has caused concerns for representatives of three multimillion-dollar conservation projects as well as officials in the environment and forestry ministries.

On December 8, the Mines and Energy Ministry signed a deal for two 500 kilovolt power lines running from the Thai border to Phnom Penh and from the Laotian border to Phnom Penh, both to be developed by Cambodian energy firm Schneitec Group. The line from Laos is set to cut through Prey Lang, a 430,000-hectare protected area that runs through four provinces. The forest is considered one of Southeast Asia’s last major lowland forests, and is flanked by concessions that activists say are behind a massive network of illegal timber trafficking.

Matthew Edwardsen, chief of party to USAID’s $21-million Greening Prey Lang project, said the project as proposed would have “implications” for the sanctuary and program activities supporting communities near it. He said the line would cut directly through two existing emissions reduction programs set up with help from both the Japanese and Korean governments.

Though it would not directly or immediately impact the potential carbon emissions reduction program that USAID is establishing, Edwardsen raised concerns over an access road that would be cleared along the line.

“The proposed transmission line route would effectively divide PLWS into two by creating a road that transects the entirety of PLWS,” he said in an email. “This would result in significant fragmentation of PLWS evergreen forest.”

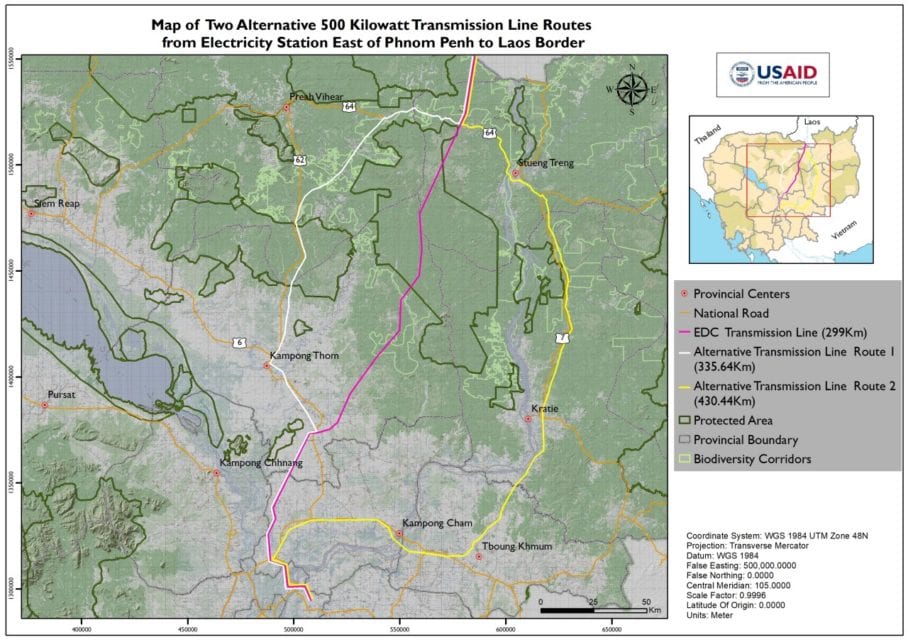

A map provided by Edwardsen showed the proposed 299-km transmission line would cut through the protected area as well as carbon-credit projects in Stung Treng and Kampong Thom provinces.

Edwardsen said his team had been informed of the project from SBK Research and Development, the firm conducting the power line’s environmental impact assessment, and that his organization proposed two alternative transmission line routes running around the sanctuary to the consulting firm to share with Electricite du Cambodge.

“While longer in length, both of [the] proposed alternative routes are adjacent to roads, follows the path of current or proposed EDC transmission lines, and minimizes the impact to Cambodia’s protected area network,” he said.

Two representatives from SBK initially agreed to speak with a reporter, but they backed out at the last minute, saying they were not allowed to disclose details because of a “confidential agreement.”

Near the southern end of Prey Lang, in Kampong Thom province, is the Korea-backed Tumring carbon-credits project, a 67,000-hectare area aiming to mitigate 3.8 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in a 10-year period through the U.N.-certified REDD+ program.

REDD+, or reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, is a global conservation scheme aimed at protecting forests through investments from high-emitting companies, governments or other entities that in exchange can claim smaller net emissions.

Chhun Delux, the Tumring project director and a Forestry Administration official, said the transmission line’s construction could affect the sale of carbon credits. He said there were two companies currently looking to buy carbon credits from Tumring, which is mostly outside the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary but in adjacent forested areas.

“We don’t know about the [transmission line] project right now,” he said. “I used to hear about it from the Ministry of Environment, but the detailed information, I don’t know, even the community doesn’t know.”

The REDD+ project would still be feasible, Delux said, but building the transmission line would encourage more small-scale clearing from opportunistic loggers, which is already a problem that the project struggles with.

“When there is a cutting of trees because of the transmission line, it will encourage other people to go to the area and do more clearing,” he said. “Adding to [what] the transmission line has already cleared, more clearings will happen in that area.”

In addition to the Tumring project, the Japanese conglomerate Mitsui has funded a separate REDD+ project, which in its first three-year phase is trying to support forest patrols and communities in and around the Prey Lang area in Stung Treng province in order to be placed on the carbon market in the future.

Jackson Frechette, a Greater Mekong landscape manager for Conservation International who works for the Mitsui project, said he had been consulted by SBK along with the USAID project team, but he still had little idea what the actual scope of the project would be, or how much damage it could cause.

But he said that any development inside the wildlife sanctuary could open the area to greater deforestation.

“[The transmission line] is creating a very nice access road through the middle of forest, so it can be potentially devastating,” he said.

At this point, he did not think the project would impact Mitsui’s decision to fund the next round of the project, which would expand its work supporting law enforcement and sustainable agriculture and other sources of income to cover more area in the forest, but it would impact the conservation work and potentially investors’ perception of the project.

The sanctuary is already under pressure from other developments, including mining exploration, targeted logging of high-value trees and clearing for agriculture, he said.

“It’s hard to argue when they say we need power,” Frechette said, though he pointed out that there are other options than constructing a power line through a wildlife sanctuary. “When it comes to a mine, we can’t control the location of minerals, but with a power line we can control it, but they’ve chosen not to.”

Frechette said Mitsui had been informed but did not seem prepared to put pressure on the Cambodian government’s decision.

“There is a certain level of integrity [involved] in purchasing those credits,” he said. “If you’re creating a system, and if there were a bunch of things like this happening, the risk is undermining the credibility of your credits.”

Representatives for the U.K.-based Virgin Atlantic Airlines said in 2018 that they stopped buying carbon credits from Cambodia’s first REDD+ project, in Oddar Meanchey province, after a research report from November 2017 presented evidence that deforestation increased after the carbon market program started.

A document on the Phnom Penh to Laos transmission line’s impact assessment that contains notes from Environment Ministry officials, seen by VOD, suggests that the ministry’s officials also did not support the project’s proposed path through the national park.

In the document, two of the ministry’s secretaries of state, Sao Sopheap and So Khan Rithy Kun, suggest that the developers consider routes that avoid REDD+ projects or the sanctuary in general, with Environment Minister Say Sam Al signing off on their comments. Sopheap and Khan Rithy did not respond to questions.

Neither the Mines and Energy Ministry nor Electricite du Cambodge responded to multiple requests for details about the transmission line construction between the Laotian border and Phnom Penh, and its potential environmental impacts.

Prey Lang’s northern and southern tips — which are partially covered by the Mitsui and Tumring conservation projects, respectively — have been blighted by forest cover loss, reaching a peak in 2019 and continuing through this year, according to forest loss alert data from the University of Maryland’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery program.

Since the beginning of this year, the Environment Ministry has suppressed a globally-recognized forest patrol group, the Prey Lang Community Network, from scouting the forest on random patrols. Global conservation scientists have lambasted the government’s decision to ban PLCN patrols, and the fragmented group of logging watchdogs has been awarded by the international conservation group Global Landscapes Forum for their grassroots work and struggles with access.

The Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary has been a hotspot for deforestation, losing a record-breaking 7,510 hectares of forest cover in 2019, equivalent to losing one football pitch-sized patch of forest every hour, according to satellite data.

Global Forest Watch, a website that tracks forest cover loss and gain via satellite imagery, detected at least 1,000 deforestation alerts per week in and near the protected area starting the week of November 2, approximately the beginning of dry season, when weather conditions improve for loggers.