Twenty-three families have ostensibly received a vacant plot on the edge of Phnom Penh’s Boeng Tamok lake — but some locals, including the village chief, suggest people have been paid to thumb-print applications to obtain lake land for unknown outsiders.

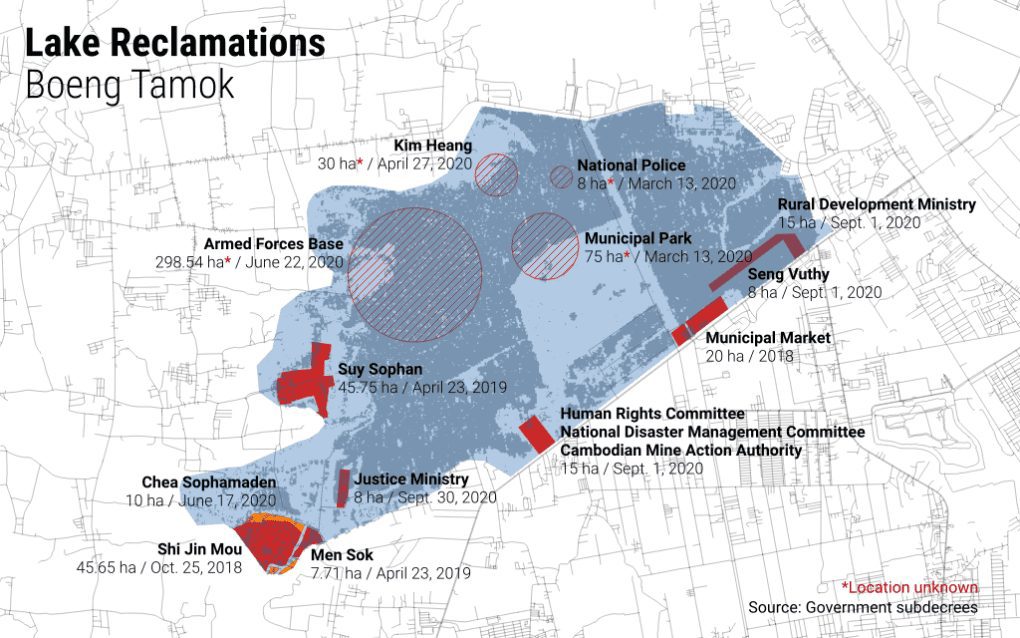

Amid a succession of lake area being granted to government ministers’ families, tycoons, the military and state institutions for landfill, a sub-decree signed by Prime Minister Hun Sen in August transferred 7.5 hectares in Prek Pnov district to 23 families, the “original owners” of the land before Boeng Tamok’s boundaries were demarcated as state land in 2016.

But the plot is vacant and partially flooded, and village, commune and district authorities say they have been shut out of the land allocation process. The two listed representatives of the 23 families say the plot is farmland, but the only supposed co-applicant they would refer reporters to — a local tuk-tuk driver — said he knew nothing of the plot or the men. A brick wall is currently being built around the area.

Kok Roka commune chief Sorn Sin said he was not involved in the allocation. He had not received any application from the 23 families in Trapeang Veng village, and no residents of his commune had ever come to his office asking for land on the lake, he said.

The national government now issues sub-decrees to allocate Boeng Tamok land, so he no longer has authority over it, he said.

“Local authorities no longer have rights to it. It’s the state’s duty to manage the land,” he said.

Trapeang Veng village chief Soeung Sim, 67, said no villagers had owned land on the lake plot since at least 2005, and likely much earlier. Sim added that no one had used the plot for years because it was flooded.

Sim said he believed the land was being obtained for “outsiders.” “They find 10 to 20 people from anywhere to give thumbprints, and give money,” Sim said. “I don’t know who is at the upper levels.”

Prek Pnov district land management department director Sou Sivutha said it should be up to the commune or village chief to check ownership claims.

He had not received any application from villagers for land on Boeng Tamok, he added.

Twenty-five people in Trapeang Veng and neighboring villages told VOD they were not involved in the land application, and were not among the 23 families who received land.

However, one resident said he was approached in the village four or five months ago by a man he did not know who asked him if he would sell his thumbprint. The resident, who declined to be named for fear of reprisals, said he just walked away before learning what it was for or how much was offered.

Another resident of 20 years said he knew of villagers aged 30 to 50 previously being sought for thumb-printing a land application, but would not elaborate or give his name. A third resident said older residents were also sought at one time, and were paid about $500 for a thumbprint.

One shopkeeper, who said her family once had land on the lake, said: “Even if I knew I wouldn’t dare to tell what’s wrong.”

Pheun Phy, 50, one of the representatives listed on the sub-decree, said at his house, before VOD knew of potential irregularities, that he had received help to submit the land application.

“Others prepared it for us. I don’t know how to write and prepare them correctly,” Phy said.

He said he had submitted the document to “authorities.” He did not have any plans for the land, but in the past it had been used to grow rice, cucumber and lotus, he said.

Sum Phal, 42, the other representative, was unclear about whether he knew of the land allocation. He initially suggested he had heard about it from villagers, then said he heard of it for the first time when VOD asked him.

Asked about the other families on the application, he said, “They are not home at this time. You cannot meet them.” He would not say whether they lived nearby.

Some had soft land titles for the lake land while others did not, and their plots were about half a hectare each, though he did not know exactly, he said.

Phal eventually provided a phone number for “Kuch,” a tuk-tuk driver he said was among the 23 families.

The man who answered the number said he was a tuk-tuk driver in the same commune, and that his name was Kuch. But he said he didn’t know who Phy or Phal were. He lived in another village and did not have anything to do with Trapeang Veng village, he said.

“I live here. Why would I have land on the lake?” he said.

Neither Phy nor Phal would comment again. After several calls to a number given by Phy, a woman asked for the reporter’s name and said she would check with VOD if he was really a reporter. She later said Phy had nothing to add.

Phal’s number was answered by a woman who said she lived in “Khmer Loeu” commune, a name that can refer to indigenous groups in northeastern provinces, but is not a commune. Further calls went unanswered. Phal was not home on a subsequent visit.

City Hall spokesperson Met Measpheakdey said he didn’t have information. Land Management Ministry spokesperson Seng Lot hung up the phone, saying he was busy.