A three-day teardown deadline handed to 69 families living along a canal in Boeng Kak I commune passed without a clash on Thursday, but after authorities previously allegedly ripped out their gardens and descended on their homes with axes, residents say they don’t believe an official’s offer that they will be allowed to resettle there if they temporarily move out.

Early this week, residents along a man-made canal in Boeng Kak I found an eviction notice along their houses, warning that they have three days to remove their homes or their homes would be demolished.

Thursday was supposed to be the final deadline for residents to clear their homes, but residents met with officials at Toul Kork district to try to negotiate for more time and space.

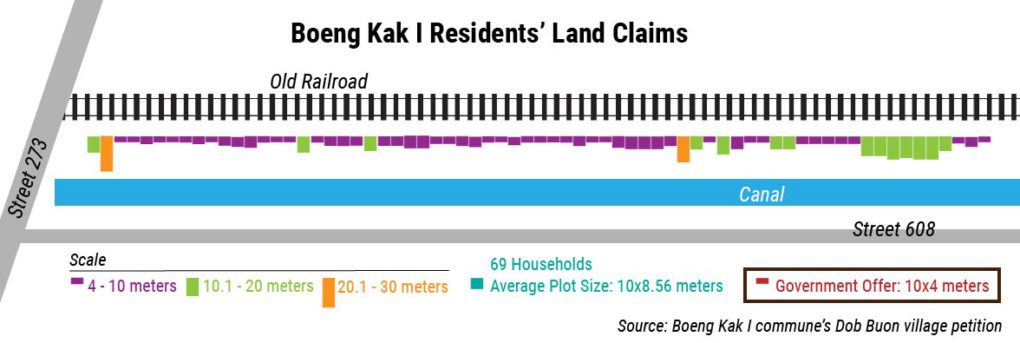

Srey Sokha, a resident and volunteer representative for the community, said the Toul Kork district governor said the community would have to leave for some time because the city wanted to fill land in the area, but they would be allowed to return and given plots of 4-by-10 square meters. The residents refused to accept the land provided by the authority, saying they would instead apply for land titles for their land.

Residents showed reporters the map of the land they occupy, which they said they submitted to Phnom Penh City Hall and other officials on Wednesday. In the map, recreated in the graphic below, all their land is 10 meters wide along the canal and stretches 4 to 30 meters long.

Sokha, 42, said she and much of the rest of the community had been living on the canal for more than 20 years.

“We don’t accept this compensation of smaller land,” she said. “Further, I don’t believe what they have planned for us because we don’t have any proof that the land titles belong to us, plus the governor hasn’t provided any exact document showing we will get 4-by-10 square meters of land after the land-filling.”

Residents said they met with the Toul Kork district governor on Wednesday, but when reached on Thursday, district governor Ek Khun Doeun said he didn’t know about the community’s concerns, directing questions to the Boeng Kak I commune chief.

The district’s offer was unacceptable, said a 40-year-old resident who wouldn’t give his name out of fear of reprisals. The residents occupy larger pieces of land than authorities suggested they receive, and if they left temporarily, residents fear they won’t be able to get their homes back, the 40-year-old said.

Residents say officials have come to wreck their homes at least twice before they were given the teardown notice, once in late July when authorities ripped a road out of their gardens along the canal, and again on August 13. On that day, around 30 to 40 officers came close to midnight with axes to tear parts of their houses down, as some of the officers burned tires around the houses, said the 40-year-old.

“I do not believe in this project,” he said. “We’re being cheated by the authorities. They called us for a meeting, but we haven’t got any request letters nor any clear information. They just came and destroyed our plants.”

Between their homes and the canal is a road of dirt, with charred remains from fires and plastic straws strewn over track marks from a heavy machine. Sokha said this road used to be filled with gardens 一 mango, papaya, sweet potato and leafy greens 一 before authorities dug it out on July 23.

Due south, separated by a block of townhouses, are the Phnom Penh City Center developments, a sprawling and largely empty development by a firm directed by businesswoman Choeung Sopheap, an elite property holder married to ruling party senator Lao Meng Khin. Her company, Shukaku, completely filled the 90-hectare Boeng Kak lake between 2008 and 2012 and violently evicted an estimated 20,000 residents, the country’s most infamous eviction that pushed the World Bank to temporarily freeze funding to Cambodia.

When asked about the community along the canal, Boeng Kak I commune chief Wat Darith claimed officials had made land titles for them two years ago but residents did not accept them. He hung up before reporters could ask more questions.

According to the 40-year-old, surveyors tried to come to their village in 2017 in an attempt to survey the land and grant titles, part of the city-wide retitling scheme. But he claims that authorities stopped them, and no surveyors have come to their community since.

Their village, Dob Buon, also includes the houses on the other side of the canal, where residents received land titles in 2019, claimed a 65-year-old resident of the community without land titles.

“[Officials] say we live in a lawless area, but that place was a lawless area before,” he said, gazing across the canal at the overgrown plants and concrete houses behind them. “They just have bigger houses. They have more money.”