Phnom Penh’s most valuable urban space is dominated by traffic that makes a mess between the riverfront and Royal Palace. In the first of a four-part series campaigning for a car-free Sisowath Quay, Ses Aronsakda highlights the idea’s potential for civic activity and commuters.

In its founding myth, Cambodians are said to be the descendants of Nagas who dwell underwater in lakes, rivers, and oceans. These Nagas of old were a benevolent force, but now a new race of mechanical, polluting serpents is choking Cambodia’s lands.

The challenge I refer to is the never-ending lines of motor vehicles that snake their way across Cambodia’s towns and cities. Phnom Penh is especially afflicted. Even the city’s most beautiful public spaces are designed not with humans in mind, but planned in a way that caters to traffic instead.

Preah Sisowath Quay, the promenade along the riverside, is a prime example of a public space and a crucial anchor point for the city’s civic life. But even in this place vehicle traffic dominates, with four fast-moving lanes disconnecting the riverside promenade from the lawn of the Royal Palace, and from the area in front of Wat Ounalom.

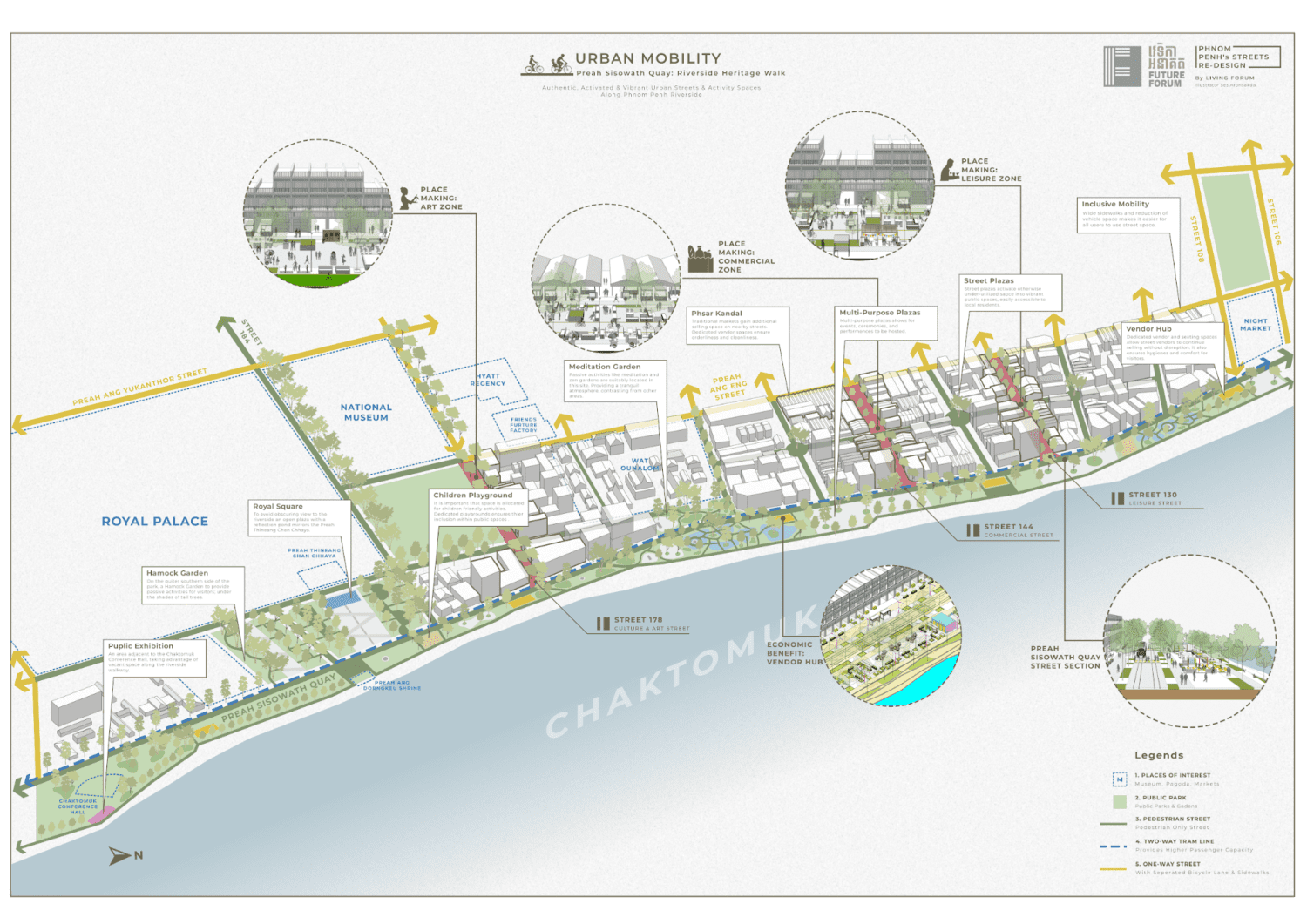

Imagine a future scenario where Sisowath Quay is pedestrianized from the Chaktomuk Conference Hall to the Night Market, offering a continuous 1.4 kilometer-long public space, brimming with social, economic, cultural and leisure activities. Driving lanes clogged with cars and motorcycles could instead be replaced by a large pedestrian and cycling thoroughfare, where instead of dangerously dodging traffic to catch a breath-taking glimpse of the confluence point of four rivers, anyone — be they young, old, riding a bike, or using a wheelchair — could casually stroll to view the river’s scenery.

Although such a radical transformation may seem daunting and obstructive, it is crucial to unlock the full potential of urban space. And it is possible to achieve this kind of change — on the riverside, and elsewhere in the city — without sacrificing the overall flow of movement around the capital.

Evaporating Traffic

The most often cited argument against pedestrianization efforts is that traffic would worsen in the affected area. In reality, follow-up studies on various pedestrianization projects in cities across the world have proven that the contrary is true. Pedestrianization can actually help a city’s traffic woes.

Whether one examines Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon park, Shanghai’s Nanjing road, or Paris’s rapid shift to reduce space for cars, traffic has consistently decreased in places that have prioritized space for pedestrians. These cities have managed to replace cars by increasing usage of public transit and making room for a surge in active commuters, as locals and visitors change their commuting behavior.

A recently completed study examining how Barcelona’s car-free super blocks have impacted traffic concluded that “On average, traffic levels on streets with interventions diminished by 14.8% relative to streets in the rest of the city.”

Encouragingly, traffic on adjacent parallel streets, which may provide likely alternative routes for traffic to displace to, did not see any significant corresponding increase in congestion. This suggests that vehicle space reduction triggers a combination of shifting choices in modes of transportation for commutes, reducing vehicle trips and road users’ trip destinations.

These are crucial findings for Phnom Penh, as the city struggles against widespread traffic congestion. A comprehensive plan to create a car-free riverside zone has the potential to positively impact traffic in adjacent areas, increase the share of riders on Phnom Penh’s beleaguered bus line, give the city’s water taxi a new lease on life, and increase the number of active commuters.

Phnom Penh should reinforce its prioritization of pedestrians along the riverside by enacting policies that decrease the convenience of car usage. As evident in Barcelona, traffic can only be curbed by cutting driving lanes, parking lots and boosting alternative means of transport.

For example, the number of parking lots available in the city’s center can be reduced by reforming parking policy to require parking maximums, reducing and cooling demand for vehicle traffic. Moreover, a congestion charge for cars entering the city’s historical core, between Norodom Boulevard and the riverside can significantly dissuade car trips as well.

To supersede car trips, the Norodom Boulevard bus line should be enhanced by disentangling its route and placing it on a dedicated bus lane. Nearby roads, like Preah Ang Yukanthor Street, can be turned into low-traffic one-way roads, calming the streets to be better suited for locals.

A Car-Free Riverside

Apart from curbing congestion, pedestrianizing urban waterfront locations opens up additional space for economic, social and cultural activities.

Cambodia would not be the only country to undertake a considerable project to pedestrianize a waterfront space. Pedestrianization projects along waterfronts elsewhere have already been carried out elsewhere with successful results.

Rio de Janeiro’s Waterfront Promenade is in many ways similar to Phnom Penh’s Sisowath Quay’s case.

In 2016, a radical transformation of Rio’s waterfront was completed, removing an elevated highway that had cut the Brazilian city’s urban fabric off from the beautiful Guanabara Bay. It restored the physical connection the city once enjoyed with its waterfront, encouraging the creation of a more inclusive, productive and active waterfront public space.

The highway was replaced by a pedestrian promenade beginning from Rio’s bustling downtown Centro district, and added a large public plaza that complements the 18th-century Paço Imperial, the former royal palace. The promenade’s wide walkways and plazas connect historical buildings like the São Bento Monastery, museums, a cathedral, cultural centers and public institutions, tying these features together into a cohesive urban fabric straddling the waterfront. Warehouses were renovated into event spaces suitable for hosting exhibitions, performances, and commercial activities.

As anchors for a city’s civic activities, pedestrian thoroughfares add much-needed green space, contribute to placemaking, and improve livability. They help diversify the economy, giving locals opportunities to open businesses, make a living, and be creative. Best of all, as public spaces they are inclusive and open to all.

Unless Phnom Penh wishes to forfeit these benefits, pedestrianizing its waterfront should be a priority. Let’s explore a possible scheme that would allow the city to maximize these benefits without sacrificing urban mobility.

Reimagining Preah Sisowath Quay

Preah Sisowath Quay is the obvious candidate to be pedestrianized, but more can be done to create a cohesive network of walkable streets beyond just one stretch of road. Smaller nearby streets like Street 5 and lateral roads from Street 110 near the Old Market to Street 184 beside the Royal Palace should also be pedestrianized.

These smaller side streets are even better-suited for pedestrianization, because they do not carry heavy traffic and are at times informally closed off due to streetside activities. Formalizing this arrangement would not be a huge leap, and by making pedestrianization permanent these streets can be redesigned to better meet the demands of local users.

Needless to say, access to vehicles providing freight and public services should be maintained by incorporating a clearway wide enough for vehicles to pass through during off-peak hours, and act as the main pedestrian and cyclist thoroughfare during peak visitor hours.

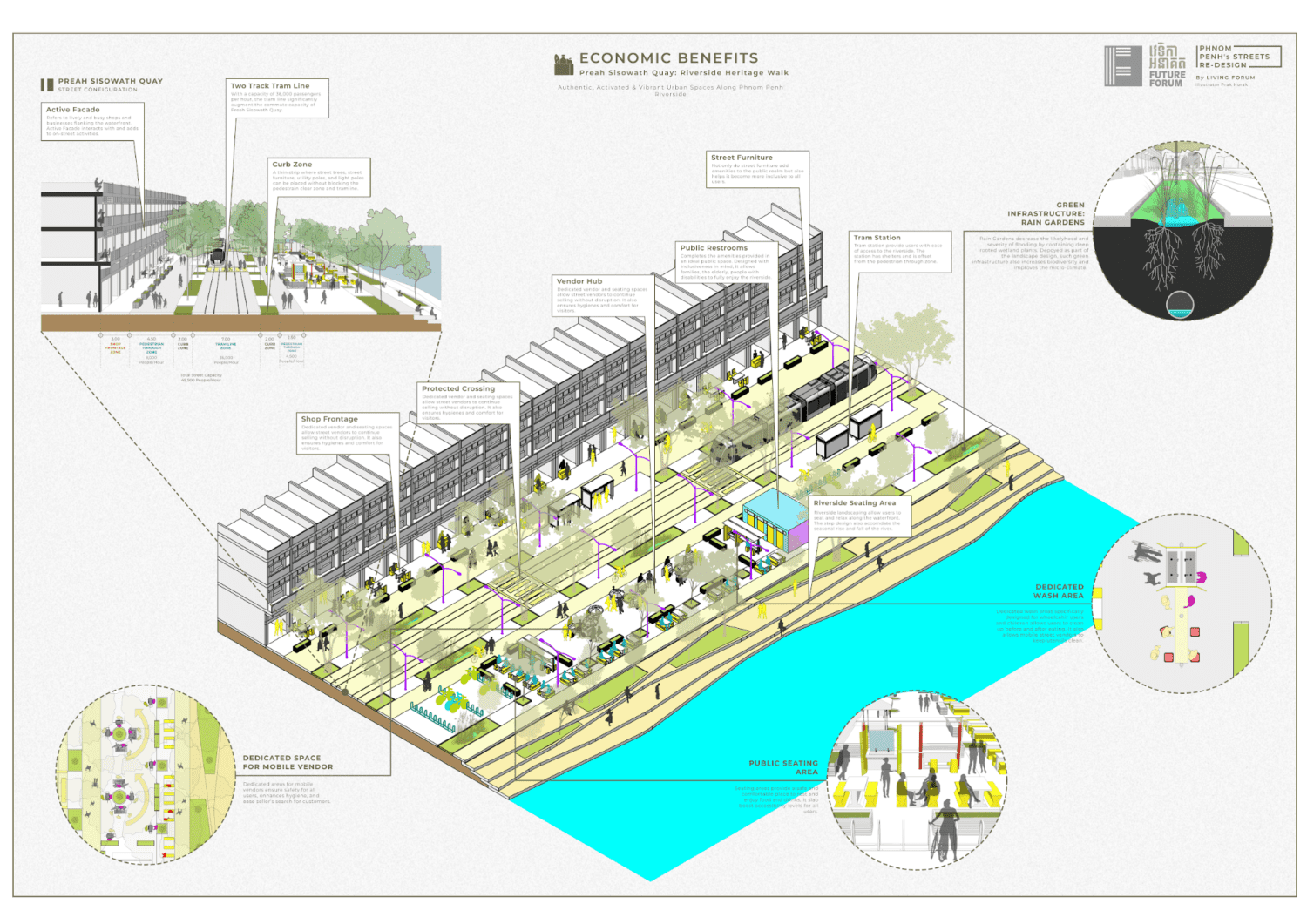

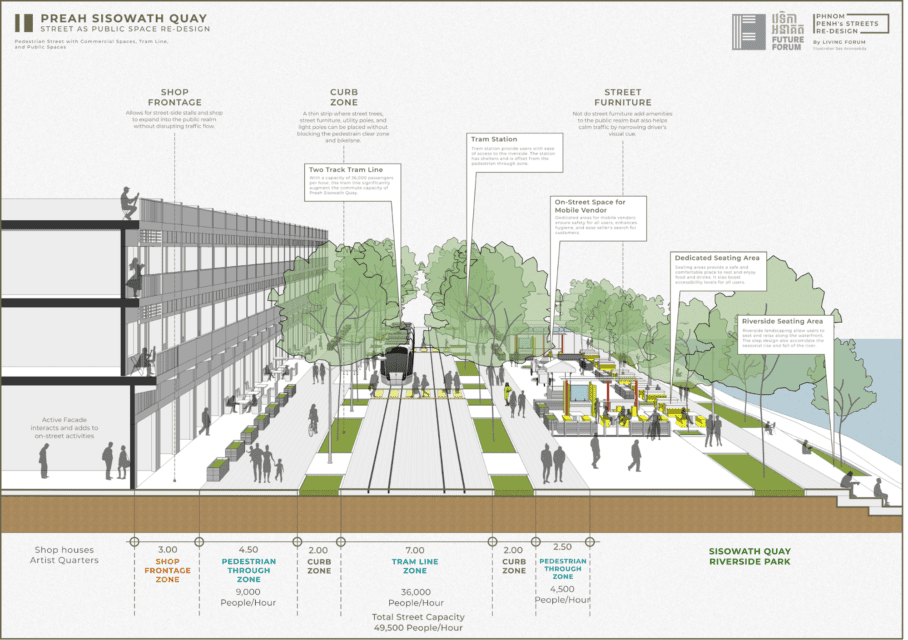

To augment traffic capacity, a tram line is proposed from Samdech Choun Nath roundabout heading north into Russey Keo district. With two tram tracks, the new Preah Sisowath Quay can carry 36,000 passengers per hour, significantly boosting carrying capacity compared to its current configuration.

Local shops are allowed to add additional seating in a 3-meter-wide shop frontage zone. Space gained can also be allocated for trees and rain gardens, providing shade and reducing stormwater runoff. Wide and comfortable sidewalks leading to plazas and vendor hubs would complete the new Sisowath Quay.

Conclusion

Phnom Penh’s riverside can be reimagined to benefit people. The city should commit to pedestrianization of Sisowath Quay and nearby streets, introducing new public transport and boosting old ones, and encouraging active mobility. Meanwhile policies like congestion charges and reduction of parking space contribute to cooling vehicle trip demand.

These efforts are crucial in significantly reducing traffic congestion in the affected area. While transforming Phnom Penh’s riverside into an economically productive, environmentally sustainable, socially active area welcoming to locals and visitors.

Fighting congestion requires us to plan for the traffic we want — public transit and active commuting — not the traffic we have. Let’s avoid using the city’s most valued urban space for the purpose of driving and parking, and instead open it up for people.

Future Forum is presenting an urban design exhibition, “Preah Sisowath Quay: Riverside Heritage Walk,” from December 18-24 at the Friends Future Factory on Street 13.

Ses Aronsakda is a junior researcher at Future Forum. Educated as an architect, he researches Phnom Penh’s urban planning with interests in all aspects of cities and urban design.