BANTEAY SREI DISTRICT, Siem Reap — Villagers who settled two years ago in Run Ta Ek eco-village — where thousands of new Angkor Archaeological Park evictees have been promised plots of land — say that poor living conditions and lack of job prospects have caused many to abandon their homes.

The area has faced controversy in recent weeks amid renewed evictions from the Angkor Archaeological Park, which authorities say is voluntary. Multiple groups have been relocated from Siem Reap to Run Ta Ek over the years, creating overlapping claims to land and cycles of disenfranchisement.

Starting in 2020, about 300 families volunteered to relocate from the Stung Siem Reap river to Run Ta Ek in Banteay Srei district, about 25 km northeast of Angkor Wat. Land authorities have said the area will serve as a resettlement site for a more recent wave of vendors and residents ordered to leave Angkor park before the end of the year.

But when reporters visited Run Ta Ek in early October, those already living there say the last two years have been defined by joblessness and hunger. Many houses were locked and abandoned, some with the owner’s phone number posted on the outside.

Nou Sophea, who relocated from Siem Reap city in 2020, said she and her four relatives have struggled to make ends meet in the eco-village. Her family has since locked up the home and returned to the city last year, renting a home while they search for work.

“There is no work to do,” she said. “Even though it has on-site villagers who grow crops and rice farms, we — the new arrival from Stung Siem Reap — don’t have any jobs.”

‘I Ran Out of Food’

Those who have tried to start a new life in Run Ta Ek say the newly-settled village offers few work opportunities, forcing family members to migrate elsewhere.

70-year-old Seng Oun received a standard 20-by-30-meter plot of land from the government when her family relocated from the Stung Siem Reap river in 2020 amid infrastructure upgrades. She makes a living selling food and small items to her neighbors. But because many villagers couldn’t find work, they moved elsewhere, shrinking her population of potential customers.

Oun’s own children have already left Run Ta Ek to find work.

“Before, there were more people, but they had nothing to eat and could not afford anything, so they decided to return back to the city,” she said. “Some children migrated, and some mothers do scavenging. Some work cleaning dishes to earn money for buying food.”

On a given day, Oun can’t even sell 5 kg of num banh chok, she said.

Another villager, Pheav Hong, 60, said his family has eked out a living selling groceries from their Run Ta Ek home. But because there are so few people living in the eco-village and no market, he and his wife have had to periodically go to live with his children at Preah Vihear province when they go hungry.

“People closed the doors of many houses, so it’s quiet, not many people … because there is no work to do,” Hong said.

“In town, they can do construction work … here, no one is doing any construction work,” he added. “Sometimes, I run out of food, close the door, and run to Preah Vihear province.”

The older man said his family has received an IDPoor card, but it doesn’t provide enough benefits to sustain their livelihood.

Officials Promise Improvements

Although 594 families living along the Stung Siem Reap river initially volunteered to live in Run Ta Ek development in 2020, only 300 families ultimately built homes and moved there, according to commune chief Chhuon Im.

The chief acknowledged that some had left the village to look for work in Siem Reap town and elsewhere, but said that the government continued to provide and process IDPoor cards for them.

“Both the previous arrival and next [group of] arrivals, the government provided poor IDs for all of them,” Im said.

Suos Narin, a monitoring officer for rights group Adhoc in Siem Reap who has personally visited the area, said he worries about Run Ta Ek’s poor living conditions. The situation is unlikely to improve without more government intervention, he added.

“They are not well-off people who can afford rice noodles or coffee like the people in the city,” Narin said. “They are poor people, so if they are doing selling, it is not possible to sell at a high price.”

“If the development plan in this area has been sped up like what samdech said, it will benefit the people with roads, water, electricity,” he added, referring to Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Land Management Minister Chea Sophara wrote on his Facebook page that the 20-by-30-meter plots Run Ta Ek residents received would be registered under their names for the next generation, and that authorities were preparing more infrastructure such as schools, health centers and electricity. Those relocating will have IDPoor cards for 10 years.

As of October 10, he wrote, 8,031 Angkor families had joined a lottery for plots at Run Ta Ek.

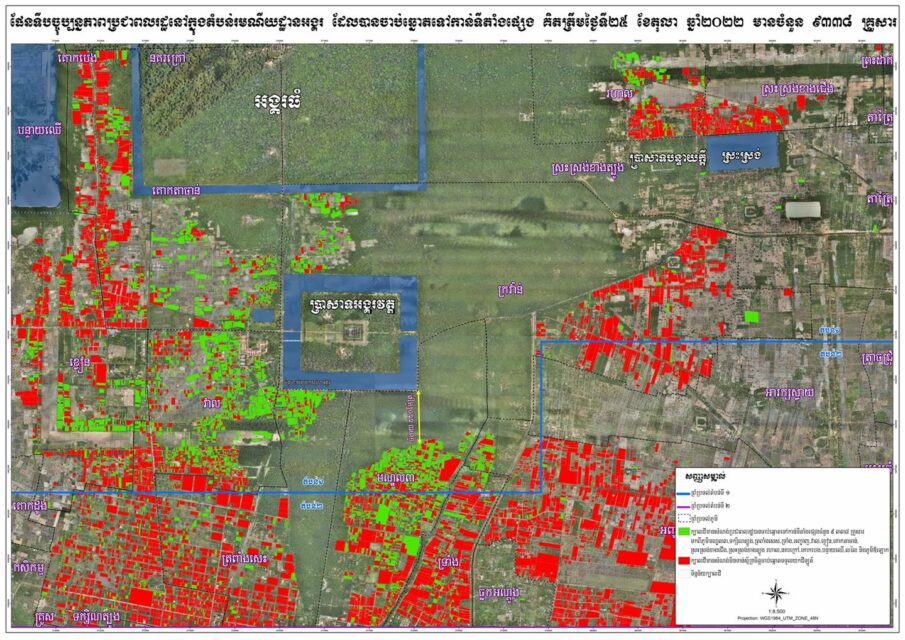

This week, he posted that 9,378 families have accepted relocation as of October 26, alongside a map showing many more have yet to agree. The Run Ta Ek site is said to be able to house 6,000 families.

New Wave of Evictees

Even as Run Ta Ek’s prior generation of residents raise the alarm about their situation, the government has pegged the area as the landing place for Angkor evictees and promised to develop another 1,112 hectares in the commune.

Yet that development plan, too, will displace existing villagers. Hoan Ravuth, who lives in Tany village in Run Ta Ek commune, told VOD that 23 families who owned a total of about 82 hectares of rice fields will lose their land to make way for the new evictees. Thirteen families have decided to accept the compensation, but 10 families have still refused, Ravuth among them.

Ravuth said that he and the other families had farmed rice on larger plots of land, but the authorities would only allow them the same 20 by 30 meters promised to new villagers.

His own family owned and worked on 2 hectares of land from his ancestors – and had ownership certificates, Ravuth said — but has since been accused of farming illegally.

Hob Touch, 63, likewise said his family worked on 9 hectares of farmland inherited from his parents, which he has kept to feed his six children and grandchildren.

Touch said it was an injustice for authorities to take his land and distribute it to other people from the Angkor area, and called for the government to give 50% of his land back along with a land title.

“While I am a rice farmer, how can I live?” he said.

Another villager Chhoeun Nou, 56, said her family owned and worked on 2 hectares of land and had been disputing Apsara’s development of the Run Ta Ek area since 2014.

She said Siem Reap authorities had visited and requested that she leave her land in exchange for a 20 by 30-meter plot. She accepted, she said, because she lost faith that land authorities would listen to alternatives.

Some of her neighbors have received court complaints after protesting over their land, she added. Chhuon Im, Run Ta Ek commune chief, said she would not comment on the case beyond noting that it had reached the court and the residents had lost.

“I protested a long time ago and lost belief in finding a fair solution from authorities,” resident Nou said. “I was hopeless. I accepted with tears, with regret. I really missed my land but I did not know what to do.”