A Cambodian translator has coined a new Khmer term for the word “Holocaust” for use in new Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) publications, including her Khmer-language version of a memoir by a Holocaust survivor that was released in Phnom Penh on Friday.

Sovicheth Meta, 21, said she translated “Holocaust,” which refers to the mass murder and genocide of more than 6 million Jews by the German Nazi regime in the 1940s, as the Khmer “bochea phleung,” which means to “sacrifice by fire.”

“The [term for] Holocaust used in the book as well as on the cover of the book is the first ever that has been translated into Khmer,” said Meta, who is also a researcher at DC-Cam, which catalogues historical materials from the genocidal Khmer Rouge period from 1975 to 1979.

“And this is also the first time this specific book about the Holocaust has been translated into Khmer,” Meta said.

The book is the 2017 memoir “Questions I Am Asked About the Holocaust” by Hédi Fried, a survivor of the Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps who settled in Sweden after World War II.

Meta translated Fried’s book of 44 questions — including “How could an entire people get behind Hitler?”; “What was it like to live in the camps?”; and “Did you dream at night?” — and her responses from Alice E. Olsson’s English translation of the original Swedish text.

While there have been other Khmer translations of books about the Holocaust, including DC-Cam’s Khmer version of “The Diary of a Young Girl” by Anne Frank, “right now, there is no word for Holocaust in the Khmer dictionary,” Meta told VOD.

In other Khmer-language books, translators have typically used the English word; written it in Khmer script based on the English sound of the word; or literally described the term as the killing of Jews by the Nazi regime during World War II, Meta said.

Her term is not a newly created Khmer word, but a new Khmer translation based on the Greek origins of the word, she said.

Jean-Michel Filippi, a professor of Khmer linguistics at the Royal University of Phnom Penh, said to his knowledge, apart from the Khmer word for “genocide,” Meta’s phrase was the first and only Khmer translation of “Holocaust,” although he found it inadequate.

Filippi said the expression “renders well the original meaning of Holocaust” — “an offering completely burnt on an altar” — but he questioned the translator’s reliance on the word’s Greek etymology.

The modern meaning of “Holocaust” equates to the “Shoah” — Hebrew for “catastrophe,” and referring to the Nazi genocide of Jewish people — and has been so popularized that “almost no one would track back this meaning to the original ‘fire offering,’” Filippi said.

“In other words, the usual meaning of the word doesn’t rely on its etymology and ‘Holocaust’ became a kind of a proper noun,” the linguist said.

He suggested using either “Holocaust” or “Shoah” in Khmer “without any attempt to translate it further” beyond providing an explanation or definition.

For Chhang Youk, DC-Cam’s executive director, the new term was accurate and reflected “the relationship of the Holocaust and genocide in Cambodia.”

Youk told VOD he hoped the Khmer version of Fried’s book would help eliminate prejudice among people “so that we can prevent such crimes from happening again and again.”

“Words matter and require a proper understanding when you use them,” he added.

DC-Cam’s soon-to-be-published research book, “Comparative Genocide and Mass Atrocities in World History,” will use the new term, “bochea phleung,” with an explanation of its meaning in a chapter on the Holocaust, said So Farina, DC-Cam’s principal deputy director.

The Education Ministry has accepted the book’s text and plans to use selections in secondary school textbooks, beginning later this year or next year, Farina said.

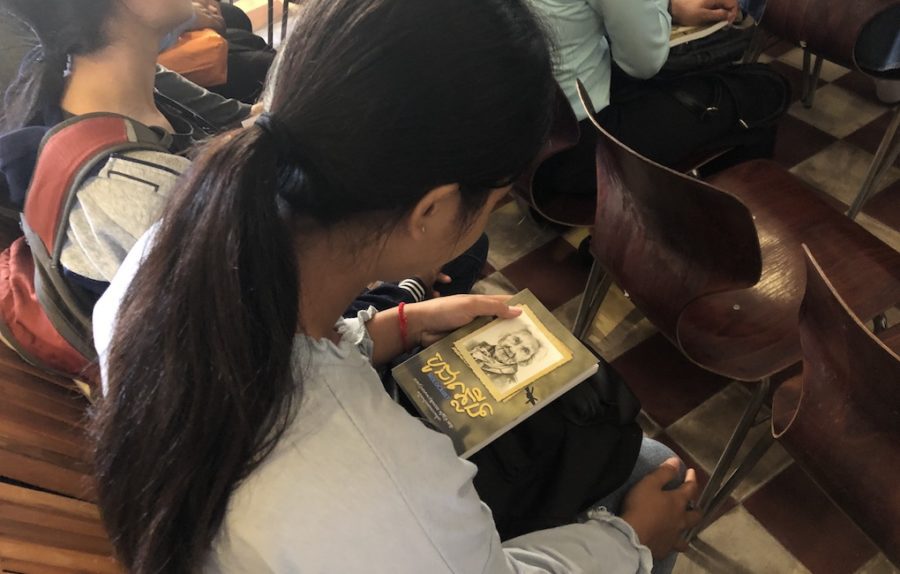

Three hundred free copies of the book, Meta’s first translated work after about a year working and volunteering at DC-Cam, were offered to a few dozen university students and others on Friday.

The translator said she hopes every Cambodian, especially youth, will be able to read the book and learn about Europe and Cambodia’s similar histories with an aim toward preventing future genocides.

“When there are no more survivors to talk about what happened, we still need to learn and teach and talk about it on their behalf,” she said.

While translating, Meta said one challenge was encountering words that didn’t have a clear Khmer equivalent. She would consult Youk, the book’s editor, or her English teacher for advice, she said.

“They told me to think first about the meaning.”