BANGKOK — In early August, 29-year-old Yu Liang* flew from Taiwan to Cambodia with high hopes to turn a new page in life, only to find himself trapped in a scam compound.

Though promised investment-related work with a high salary, fancy accommodations and nice meals, Yu’s reality turned out to be “worlds apart” from what he was told. He was forced to recruit other workers and engage in various scam schemes. His passport was confiscated and he never received a salary. He was threatened with a large ransom when he tried to quit.

Within a month of arriving in Cambodia, Yu was moved twice. His first move was from a compound atop Kampot’s Bokor mountain to the notorious Kaibo compound in Sihanoukville, he said.

The second move saw him and dozens of workers in his company transported for thousands of kilometers, across an international border, from southern Cambodia to northern Laos.

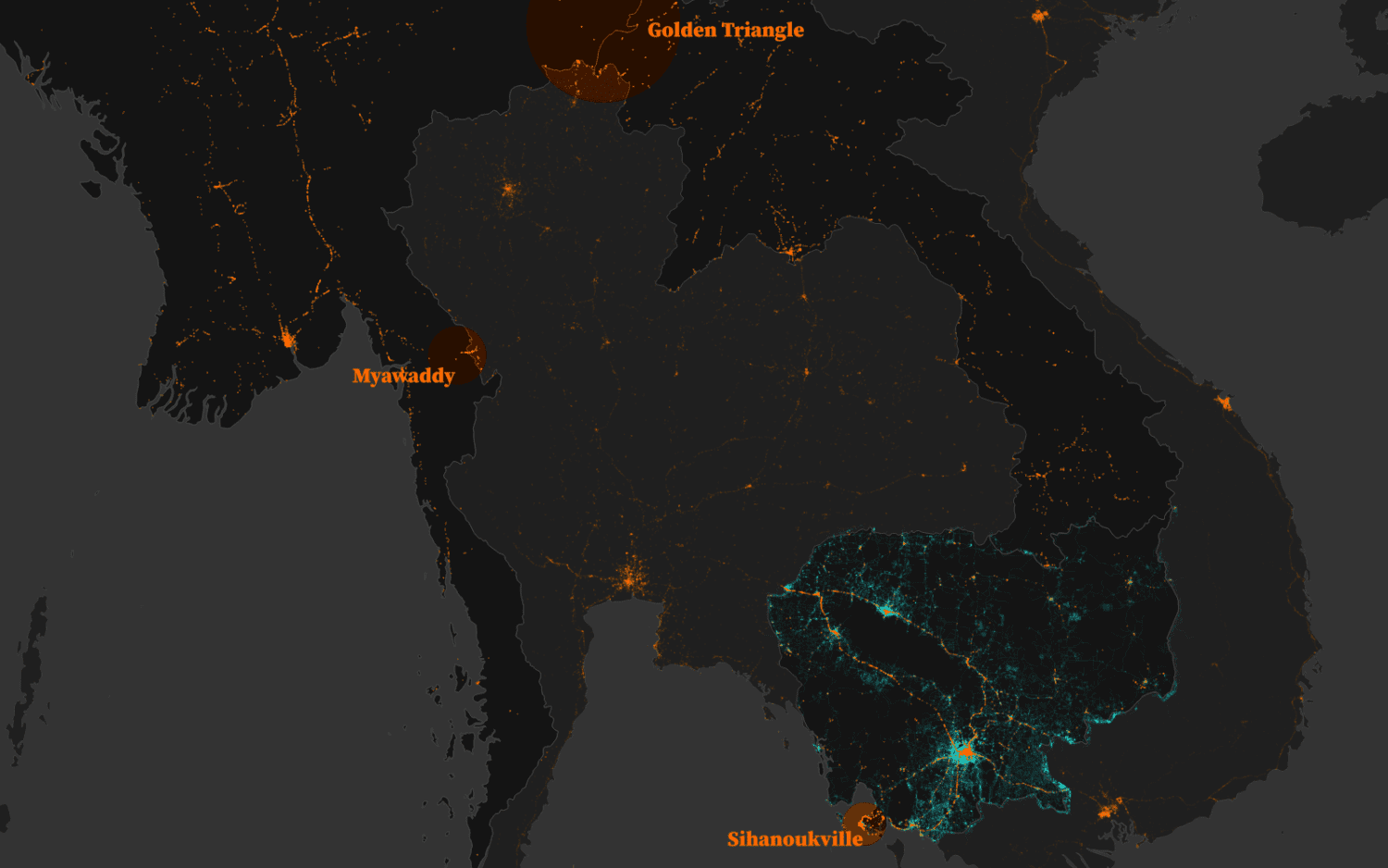

Amid intensified raids, arrests and crackdowns, signs are suggesting that scam syndicates that have been plaguing Cambodia may have started trickling out to other countries, as reports of an increasing presence of scam networks have emerged in Laos and Myanmar. Accounts from victims and a rescue group indicate that at least some scam operations are going to great lengths to relocate workers from their original bases to a new country to evade capture.

Yu told VOD by phone last week after being rescued and returning home to Taiwan that he was moved to Cambodia’s immediate neighbor Laos. Meanwhile, an NGO told of some Thai scam workers being moved from Cambodia to Myanmar.

Jaruwat Jinmonca, vice president of the Immanuel Foundation, a nonprofit that has been working on human trafficking issues in Thailand including rescuing Thai nationals forced to work in scam compounds in Cambodia, said the foundation had received requests for help from at least 27 Thai people claiming they have been forcibly moved from several locations in Cambodia to eastern Myanmar’s Myawaddy, located along Thailand’s western border.

“They said they were moved from Sihanoukville, Poipet or Koh Kong … as Chinese [scam] investors moved to Myawaddy,” he told VOD by phone. “They were not [flown] from Cambodia directly to Myanmar, but were moved through Thailand first.”

None of the relocated Thai workers had yet been rescued, Jaruwat said. He added that they are still in the process of coordinating with the Myanmar authorities.

According to Jaruwat, “a network of agents” moves workers through the land border by cars that are constantly switched along the way to avoid law enforcement. They mostly come in Thailand through Sa Kaeo province, along the eastern border with Cambodia, before exiting the country through Tak province, on the western border with Myanmar.

The drill is similar to what Yu experienced. After around two weeks of being forced to work on scams using fraudulent e-commerce websites in Sihanoukville, he and more than 100 other workers in his building were suddenly told to move in the middle of the night.

“We had just showered and were getting ready to sleep,” he said. “The boss told us to quickly pack all our bags and luggage and gather at the bottom of the building.” They were told to bring their work computers and phones with them. Yu noticed the office was emptied out.

The workers were divided into groups and then transported in vans to a hotel in the center of the city. “As soon as we checked in, the supervisor told us not to leave our rooms,” Yu recalled. It was then that he learned they were going to Laos.

Yu said they waited several nights at the hotel, then again in the middle of the night, they were suddenly told to move. Yu was squeezed into a van with seven other people. They spent the next three days on the road, moving through rough mountain roads, changing vans twice, before reaching their destination in the Golden Triangle area.

New Base, Same Work

When Yu arrived in Laos, he was placed in a three-building compound near Kings Romans Casino in the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, he said. After three or four days, the workers began familiar work based on a fraudulent e-commerce platform with which they targeted Taiwanese women.

The Thai rescue group’s Jaruwat said Thai workers who had reached out to him after being moved to Myanmar had told of similar experiences.

“They were put in [a building] that looks like a casino to commit fraud and scams. There might be some new tricks, but the pattern remains largely the same as what has been happening in Cambodia. They are also locked up and forced to work,” he said.

Jaruwat said these scam managers chose to move away as a result of Cambodia’s increasing scrutiny, and transporting workers across countries was not necessarily too complicated for those who run the operations.

“Mostly, Thai [workers] can get into Thailand without a problem. Once they are in Thailand, it’s very easy to move them,” he said. “Some of them are also not forced workers. They are willing to do it, and the guides would know exactly how to take them across the borders.”

Last month, Thai police launched their first raid in Kandal province, which shares a border with Vietnam, and suggested that scam networks in Cambodia might have started relocating away from their original hotspots like Sihanoukville or Poipet due to tougher police investigations.

There might be some new tricks, but the pattern remains largely the same as what has been happening in Cambodia. They are also locked up and forced to work.

Jaruwat Jinmonca, Immanuel Foundation

Arrests in Transit

Over the past year, Thai social media has been bombarded with scam job ads with classic descriptions for positions like “admin” or “online marketing,” promising high salaries and the perks of working overseas with free accommodation and meals. The ads were especially common in groups targeting people looking for work near Sa Kaeo province, which neighbors Cambodia’s Poipet. Now the same type of ads have started to appear more often in job groups for people looking for work near Tak’s Mae Sot district, which shares a border with Myanmar’s Myawaddy.

Late last month, the Thai military intercepted and arrested nine Chinese nationals being moved on the back of a truck in the northern Chiang Rai province. According to Thai news reports, all Chinese testified that they worked with a phone scam network in Myanmar’s Tachileik and were fleeing Myanmar authorities.

The Chinese were found with 45 phones and “some cash” on them, and their suspected smuggler — a local municipal official in Chiang Rai — was also detained, the reports said.

Last week, the Cambodian military stopped 16 Chinese nationals who were being trafficked from Preah Vihear province into Laos, said Preah Vihear’s Chheb district police chief Chhuo Mady on Friday.

Four vehicles were stopped around 7:30 p.m. Tuesday. The vehicles were confiscated and the 15 Chinese men and one woman handed over to immigration police, he said.

Deputy provincial police chief Tan Kimleng added that two Cambodians were arrested the same night for their alleged involvement in human trafficking and sent to court.

The Immanuel Foundation’s Jaruwat said he began hearing about this kind of movement of scam workers around July this year. Thai authorities have so far made no official reports of scam workers being smuggled from Cambodia to Myanmar through Thailand. Two Thai police officers who are often involved in such investigations denied any knowledge of it when contacted by VOD. Both, however, agreed that it was “possible.”

Jaruwat voiced concerns about the possible explosion of scam operations outside Cambodia — especially in Myanmar — but he thinks the movement of workers is only a temporary phenomenon.

“In a while, I think this won’t be happening a lot. Now, the Chinese still need workers [as they are relocating] to continue the businesses,” he said. “When they are done relocating their base, they will soon start recruiting people directly from Thailand.”

In Laos, Yu was demanded a $7,000 ransom if he wanted to go home. He only found this out after his sister in Taiwan called on Chang An-lo, a politician nicknamed “White Wolf” and a former leader of the Bamboo Union triad, for help — and 2,000 km away in Laos, Yu was called into a meeting upstairs with his bosses. They told him that police were looking for him, and he said he was taken into a “ransom room” on the 11th floor, handcuffed for two days without water or food, then told to gather enough money to pay the ransom.

The Taiwanese politician was able to negotiate the ransom and organize a rescue through a friend in Chiang Rai, Thailand, to which Yu was taken by boat, he said.

“I felt imprisoned the whole time,” Yu said, now back in Taiwan. He wouldn’t easily believe people again, he added.

Additional reporting by Mech Dara

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of human trafficking victims.

This article is produced with the financial support from Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung in Southeast Asia via its Hanoi office.

This article is produced with the financial support from Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung in Southeast Asia via its Hanoi office.