When Phnom Penh authorities tore apart her fishing nets and dismantled her floating home, Phla unlatched her longboat from the shores of the Tonle Sap River on the capital’s outskirts where it had been docked for decades.

Piloting a roofed wooden boat — sturdier than the lithe motorboats that her community uses for fishing, and sometimes sleeping — she and her four children followed the Tonle Sap from Prek Pnov district to where the river empties into the larger Mekong and continued south for four days in June until she reached the Vietnam border. There, near Ka’am Samnor Loeu village, she’s been passing time with around 100 roofed motorboats and houseboats tethered together at a mucky depot where dredging boats dump sand pulled from the riverbed onto land.

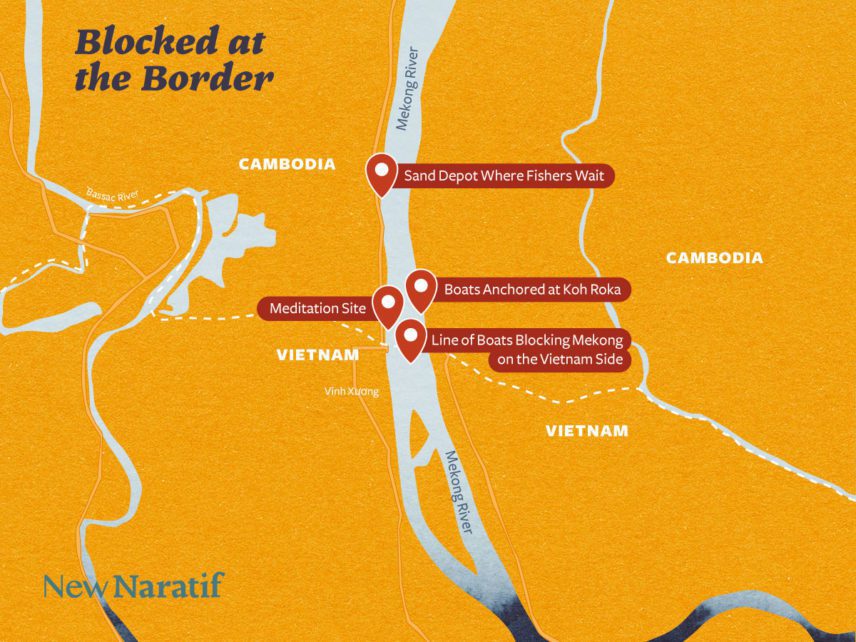

Every morning and evening for at least two weeks in late June and early July, Vietnamese marine officials float by with a loudspeaker, warning the boat-dwelling community in Vietnamese that they should not cross the border now but will be allowed eventually, without specifying when. Some 6 km south, a row of shipping boats and dredgers hold a line across the Mekong, blocking the mostly ethnic Vietnamese fishers from entering Vietnamese waters.

“I don’t want to stay here anymore,” says Phla, not only referring to her spot in the water behind the mounds of sand, but to Cambodia, where she’s lived for more than 30 years.

“Over there [in Phnom Penh] I do not have any place to live on land,” says the 45-year-old woman, who only gave her first name. “I just want to have a place to live on my boat and build my fishing net again.”

When Phnom Penh authorities in June ordered the eviction of fishers living in floating houses on the Tonle Sap within 10 days, it splintered communities of the long-staying ethnic Vietnamese minority group, who now find themselves stuck at the border with an uncertain future, pushed out and still stateless amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Phnom Penh muncipality ordered a ban in early June on floating dwellings and attached fish farms, which are mostly inhabitated by ethnic Cham Muslim Cambodians and minority Vietnamese, many who were born in Cambodia or lived there for years. The government notice cited concerns about pollution, but a district official has said the evictions were ordered in preparation for Phnom Penh’s hosting of the Southeast Asia Games in 2023. The government initially gave residents a week to relocate, sending some into a flurry of dismantling houses and boats while others stalled, demanding more time to figure out where to go.

Their calls were joined by Vietnam’s Foreign Affairs Ministry, which on June 10 said it was monitoring the evictions in Phnom Penh and wanted to see fishing families offered resettlement in a place with infrastructure as well as access to social services.

When the initial eviction deadline of June 12 came, Phnom Penh officials urged people with homes on the water to dismantle them promptly without designating a new space where they could live. Some who still had fish penned in nets under their homes to sell were allowed to float almost 6 km upstream to Samraong commune, at the capital’s northernmost edge, and given up to six months to sell off their fish and figure out where to go next. Others sold their remaining fish quickly and cheaply, and floated away.

Moving onto land is not an option for many in Phnom Penh’s waterborne community. Many of the evicted population are ethnically Vietnamese, and claim to have lived in Cambodia for decades, if not their whole lives, and unlike the majority Khmer and minority Cham people they fish alongside, they largely lack citizenship in Cambodia (or Vietnam), leaving them ineligible to own land in the country.

Despite casual prejudice against Vietnamese being commonplace in Cambodia, the newly evicted people who spoke to reporters say they did not face hateful remarks or discrimination from the Khmer people who live on the land above them, instead saying most have been pleasant or even donated food to the displaced fishers. But the history of Vietnamese occupation in Cambodia and the racist views held by some Cambodians about Vietnamese people’s supposed plot to grab Cambodian land leave the evicted community with few options for resettlement, throwing the stateless population into a whirlpool where they have few advocates — and now, no place to go.

So Phla and hundreds of others decided they had enough, and are trying to move themselves out of Cambodia.

At the Edge of Cambodia

From the Vipassana meditation center in Ka’am Samnor commune, a loose formation of ships is visible on the Mekong river, stretching across the border and deeper into Vietnam. That formation is not a usual sight, and it tightens at night, according to a Cambodian man at the center, who declined to give his name.

“Two or three days after the Phnom Penh governors announced the eviction of the floating houses, the boats arrived here, and some tried to cross the border, but the Vietnamese authorities brought them back,” he says.

A few dozen boats are visible from the pagoda across the Mekong, now docked on the opposite bank of the river’s 1.6-km width in Prey Veng province’s Koh Roka commune, after they were stopped from floating downstream to Vietnam, the man says.

“For the Cambodian people who immigrate to other countries like Thailand, for example, [governments] send them back without considering the spread of the Covid-19 virus,” he says. “But for Vietnam, they do not accept their own people back. This is very difficult for them.”

Both Vietnam’s Foreign Ministry and its embassy in Phnom Penh did not respond to emailed questions. In a late June report by Vietnamese state media, a border official in the country’s An Giang Province said the crossing at Vĩnh Xương — just south of Cambodia’s Ka’am Samnor commune — was still open to Vietnamese people going to Vietnam, but authorities did not have the capacity to quarantine everyone trying to enter.

Most of these long-term residents have more genuine links to Cambodia than Vietnam and see Cambodia as their home. Yet, Cambodian authorities frequently presume them to be Vietnamese nationals without verifying any proof of such status.

From National Road 1, as one drives through Ka’am Samnor Loeu village toward the border, there’s no sign of the ethnic Vietnamese enclave evicted from the capital. Their boats and floating homes are blocked from view by a desert-like expanse of dredged sand. The dunes plateau into the Mekong river, where fishing and house boats are lashed together by a tangle of ropes. Fishers move between vessels by leaping into the water and pulling their boats between others, or paddling through the narrow spaces between crafts — easier than sinking into the Mekong bank’s black muck.

When Phla speaks of Vietnam, she calls it “my country,” saying she was born there and her parents and relatives still live there after fleeing Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge regime of 1975 to 1979. The regime targeted ethnic Vietnamese, among other minority groups, for extermination. Phla left her parents around age 15 to cross into Cambodia, and unable to afford a trip home, she has stayed ever since, she says.

She never managed to get a Cambodian identification card, which is necessary to own land and get proper birth certificates for her Cambodian-born children. Earning$2.5 a day or less fishing, she also could not afford the immigration card that many Vietnamese residents of Cambodia have.

Another ethnic Vietnamese woman, who gave her name as Sok as she sat with her husband under her longboat’s sunshade, says the couple had just paid authorities in Kandal Province’s Ponhea Leu commune 30,000 riel ($7.5) each for immigration IDs shortly before the eviction. She was born in Cambodia, she says, and only left for a few years when she was young, during the Khmer Rouge regime and civil war.

“The immigrant card does not really help us with anything. We are just giving them the money,” she says, adding that police check their immigration IDs and charge them fines when they travel away from their community.

Traveling to the border with hopes of entering Vietnam seemed natural after the fishers were evicted from Phnom Penh, but the move has left Sok feeling directionless.

“I don’t know why they do not let us enter,” she says of Vietnamese authorities. “[Phnom Penh authorities] forced us to leave. Now we do not have a place to live. We are just stuck here.”

In an emailed statement, the U.N. human rights office’s Cambodia representative Pradeep Wagle raised concern about evicting the residents on the water, saying it should be a “measure of last resort” for which those evicted are properly compensated. The government said it supported fair and transparently negotiated evictions in a 2019 rights review. Keo Remy, head of the governmental Cambodian Human Rights Committee, did not reply to a request for comment.

Wagle adds that as stateless people, ethnic Vietnamese who do not have a permanent resident card, and their children born in Cambodia without birth certificates, can be tossed into a “spiral of rights restrictions,” infringing their rights to education, health, social security and employment.

“The fact that many of the ethnic Vietnamese population are stateless and lack nationality results in a range of obstacles in their daily lives,” he says.

For the communities at the border, health care is becoming a burden.

Kim Hea, a 35-year-old mother of four, says she and her family have been forced to live on their boat for about two weeks as of late June.

“It is very miserable to be here,” she says. “My children are very small. It is very difficult to sleep on the small boats. In the evening, there is usually strong wind and rain destroying our tent.”

She too is hoping for Vietnam to open the border, where she would like to live on land and take any factory job she can get. Though Vietnamese officials offer food once a week, she says she needs more. The food aid is just rice and some vegetables, so she has to buy meat or rely on the fish she would otherwise sell, and she needs more medicine, as her children have gotten sick amid monsoon rains.

“I just have a few medicines left. No one has come to help us with medicine,” Hea says.

Wagle, from the U.N., says his office has urged Cambodian authorities to stop the evictions “until more durable solutions for those affected have been put into place,” and engage with the people living in floating communities in order to develop appropriate measures.

The U.N. office, he adds, “remains concerned at how evictions will impact people, many of whom are poor and extremely vulnerable, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic when marginalized communities are already struggling”.

Identity Marked by Migration

The only time Nhung, a 61-year-old resident of waterways in Prek Pnov commune, says she left Cambodia was at the start of the Khmer Rouge period, when ethnic Vietnamese people fled to escape targeted killings. Though her parents are Vietnamese as well, they had long lived in Cambodia, she says, and they returned to the country once the genocidal regime fell.

Like Nhung, many Vietnamese Cambodians fled to Vietnam during the Khmer Rouge’s time in power and then returned under the Vietnam-backed People’s Republic of Kampuchea at the request of Vietnamese officials. However, Cambodia’s denial of their legal status during the 1950s through 1975, and later the destruction of documents and forced migration under the Khmer Rouge, make it hard for ethnic Vietnamese people to prove their connection to Cambodia today, as noted in a 2012 study of long-staying communities’ legal status.

Though ethnic Vietnamese are not violently attacked and killed as they were leading into the Khmer Rouge period, during their rule and in the early years of Cambodia’s modern government under the U.N. Transitional Authority in Cambodia, the minority group continues to face discrimination. Leaders of the political opposition have deployed racist, nationalist rhetoric as a tool to provoke voters to join their cause, claiming Vietnam operates a shadow government within the ruling Cambodian People’s Party and stoking fears that Vietnam is encroaching on Cambodian territory.

The fact that many of the ethnic Vietnamese population are stateless and lack nationality results in a range of obstacles in their daily lives.

In recent years, the government launched campaigns that put the population into more vulnerable positions, revoking “improper” national identification documents from ethnic Vietnamese people starting in late 2017, and from late 2018, evicting floating village residents living on the Tonle Sap lake in Kampong Chhnang province. Though Kampong Chhnang authorities evicted Khmer and Cham residents alongside Vietnamese people, the relocations highlight the rift in the state’s treatment of families of different ethnicities, according to Christoph Sperfeldt, an honorary fellow at the University of Melbourne’s Peter McMullin Centre on Statelessness who has long studied the minority group.

“Apart from affecting the livelihood of traditional fishing communities, the relocations have highlighted the precarious non-citizen legal status of relocated Vietnamese residents, as [they] have no right to own the land and instead are required to rent the sites they were moved to,” Sperfeldt says.

Though he says the floating homes often lack proper waste management and can contribute to pollution in rivers and lakes, Sperfeldt adds that the communities’ rights to life and livelihood must be respected through consultation, the provision of relocation areas with sufficient infrastructure and access to education and health care, and documentation granting them rights in Cambodia.

“Indeed, most of these long-term residents have more genuine links to Cambodia than Vietnam and see Cambodia as their home. Yet, Cambodian authorities frequently presume them to be Vietnamese nationals without verifying any proof of such status,” he says. “There is a need to open pathways for a more secure legal status in Cambodia for these long-term residents.”

Six Months Left

Since returning to Cambodia in the 1980s, this year was the first time Nhung, the elderly woman in Prek Pnov, had to move her home. She says she lived in fear for the last two years, hearing vague warnings from officials that their community would be removed from the banks near the local public hospital. When that day finally came in June, she followed other residents north to Samraong commune, where she was told she could take three to six months to sell the fish remaining in her nets below her floating house.

Just north of the Kruos pagoda, hundreds of boats and floating fish farms are docked at their new space on the river, joining together from communities across the four faces of Phnom Penh’s intersecting rivers. Their new posts are spaced farther apart and almost in a grid formation, differing from the cluster of boats and ropes anchored close to the Vietnam border. On a late morning in early July, people only appear to travel for business: A young man steers a boat full of fish to a floating fish shop, and a woman slowly paddles past to hawk ice, energy drinks, chips and sweets.

Nhung does not know what the future holds. Cambodian officials have told the residents of this unofficial floating village to follow the Mekong to Vietnam, but she has heard the border is closed.

“We have no land; how can we move up?” she asks. “Those who have money can buy the land upstairs, but for us, we do not have any money to buy the land; we will have to go back to Vietnam. I don’t know what to say now. We are just trying to survive with the help of food from other people.”

There is a need to open pathways for a more secure legal status in Cambodia for these long-term residents.

Yin Oudom, an assistant to the Samraong commune chief, says local authorities did what they could, giving some fish to the hundreds of newly arrived residents. The eviction was ordered by people above his authority, he says, claiming he does not know why authorities chose to push families away from the riverbanks in June nor what will happen to them after. Phnom Penh and Prek Pnov district authorities could not be reached after multiple attempts.

Oudom says he facilitated Covid-19 vaccinations for the new residents as part of the capital’s jab campaign, and the Samraong floating residents who spoke to reporters in early July say they have received both doses.

“As you can see, there are so many of them, arriving from Chbar Ampov, Russei Keo, Chroy Changva [districts] into this commune,” Oudom says. “The officials are unable to sleep, and there is also the Covid-19 problem. We have so many things to focus on.”

A 52-year-old fisherman in Samraong commune who declined to give his name says he is actually half Cambodian, born to a Khmer father and Vietnamese mother, but he is classified as Vietnamese, holding only an immigration ID card. Rather than trying to float to Vietnam, the man says he will try to earn money to move onto Cambodian land once he is forced to leave the waters at Samraong. The landed residents have been kind to him and his family, he says, and since he has to visit the hospital once a month to receive medicine for his heart condition, moving to Vietnam is not an option.

Without a Cambodian ID, moving onto land will be a challenge, but it is no less predictable than his future on the water.

“I do not want to go anywhere as I have always been living here in Cambodia. They asked us to move, and we don’t know where to move exactly. For now, I don’t know what is next. I have to follow what they have planned for us.”

This article was produced as a collaboration between VOD and New Naratif.