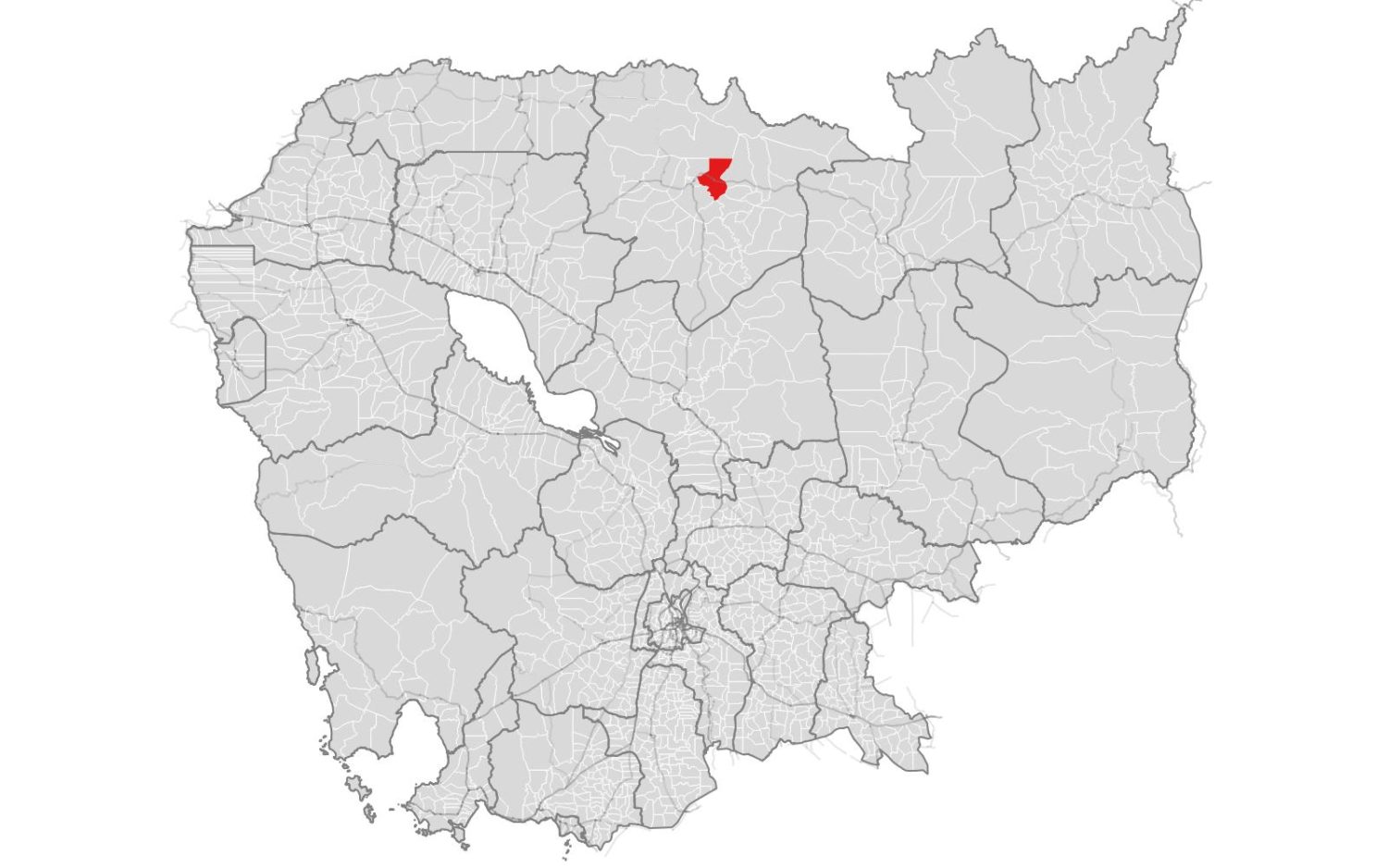

Thon Sot boarded his koyun and took the usual route to his farmland in Preah Vihear’s Brame commune in February. The 58-year-old farmer drove along Road 64, which heads towards Stung Treng, took a right just before the abandoned Rui Feng sugarcane factory and arrived at his farmland.

The farmer was shocked to see people already on his land. They were tilling the land and preparing it for planting cassava. Four people with two tractors were doing the tilling. He politely asked who they were and why they were on his and other village residents’ land, not wanting trouble.

An argument ensued. Sot said the “new people” did not tell him who they were or where they came from. He had never seen them before. In the meantime, someone had called the district police, who broke up the argument.

“But the next day they continued plowing,” Sot said, adding that they didn’t stop after that.

Other farmers who also confronted the new people were told one of the four was a manager at Rui Feng and another used to work at the company’s factory. Sot speculated they are likely from outside the commune or from even further — Kampong Thom or Prey Veng — and the vacant land was attracting new occupants.

“Others, they can do farming. But people from here cannot,” he said.

Sot previously spoke to VOD last year when he detailed how village residents, mostly ethnic Kuy villagers, had reclaimed land from five sugarcane companies holding a combined 40,000 hectares across four adjoining provinces. The $360 million company, referred to combined as Rui Feng, was expected to make Cambodia a sugar-producing powerhouse of the region but has now fallen silent.

Village residents who had lost land to the sugarcane plantations were taking back their land last year despite purported company representatives preventing them and threatening farmers. The land was also hosting large rice and cassava crops, with little to no sugarcane in sight.

February’s alleged land grab affected around 10 families, Sot said, and he lost “a lot” of land — the village resident is not one for measurements. Last year, he pointed at two spots in the plantation and said that was the land he planted.

But that was not the end of Sot’s woes.

In April, police walked into his home in Brame village, read out a summons letter and left. They didn’t even give him a copy of the letter. He and four others were expected to appear in provincial court on June 1 and was under investigation on murder-related charges. His lawyer, Sek Sophorn, said the charges were for making threats to kill and to damage property.

“We spoke politely to them and did not even hold sticks,” Sot said, denying ever getting into any kind of physical altercation. “Because if we held sticks maybe we would have been arrested.”

The Candidates

As Sot faces the scary prospect of a criminal charge, in addition to dealing with a more than decadelong land dispute, commune residents said there was little hope for a resolution from any party.

Residents have long accused local officials — including the sitting CPP commune chief — of siding with Rui Feng and refusing to acknowledge their claim to the land as an indigenous group.

After learning of the summons, Sot went to commune chief Thean Heng but to no avail.

“When I told the commune chief, he did not say anything. He often accuses people of taking the company’s land,” the farmer said.

With less than a week to the commune election, Brame’s residents have three parties to choose from: the ruling CPP, a surprise challenger in the Candlelight Party and the Khmer National United Party, which came in a distant third in the 2017 election.

The CPP’s Heng said he was unaware of the summons for Sot and the others, and was not informed about the court complaint either. He also did not know who had filed the complaint and guessed they were residents in one of the commune’s villages.

The chief also denied siding with the Chinese company, as alleged by residents, and said the land was now state land and possibly being rented to people by those at a “high-level.” He was unsure if the prolonged land dispute would affect his chances at retaining his seat this week and leans on blaming those who are prochang, or opposition.

“It is just normal that not everyone will vote for me. Every place has issues and there are other opposition parties making this conflict into something bigger,” he said.

In Brame village, Sin Soeun has just returned from a Candlelight Party rally in the capital town, led by party vice president Son Chhay. Soeun is the party’s candidate for Brame commune.

He used to live in the neighboring Chheb district, but moved to Brame around 30 years ago after getting married to an ethnic Kuy woman. He was part of the commune council in 2017, when the CNRP’s top candidate and land dispute-affected resident Khum Rany was elected second deputy chief. Since then, Rany has slipped down the ballot to the Candlelight’s fourth ranked candidate.

Soeun said he is aware of the commune’s problems and lists land disputes and deforestation as the chief worries in the area.

South of Road 64, while the Rui Feng dispute has lingered for more than a decade, villages on the edges of the Prey Preah Roka protected forest have seen the woodlands destroyed, with satellite imagery showing a fast-emerging patchwork of clearings.

While Soeun is quick to point out the two big issues, that’s the extent of his engagement with them, especially the Rui Feng dispute. He knows that commune residents had lost land and were trying to restart farming the lands, but he hadn’t spoken to his potential electorate about recent events or ways in which they continued to face rights violations.

“I do not know well about this conflict,” he said, laughing nervously and throwing sideways glances at a friend sitting at the table.

Pressed on his understanding of the Rui Feng dispute, Soeun said he has “no right” to solve it so he hasn’t asked or talked to affected village residents.

He had only heard about the February altercation between villagers and “newcomers,” and again had little to say about it.

“I did not ask, but people told me. I have no right to ask,” he said, adding that he had not held village-level meetings with residents to talk about these issues ahead of the elections. These meetings are a common feature for political parties and candidates in the run up to the campaign period.

Rany, the outgoing second deputy chief, was affected by the Rui Feng dispute and used the experience to inform her 2017 campaign. Reporters found Rany’s home locked in Brame village last Friday. Neighbors and her mother said she was harvesting crops at her farmland in Prey Roka forest and could be away for up to a week, they said. Rany does not use a phone.

She then called reporters using her mother’s phone on Sunday after returning to Brame. She said she had told the district Candlelight leadership she would like to be a candidate for the June election.

After a lot of jostling within the party, she was first picked to be the third-ranked candidate; a week later she was dropped one spot to No. 4 on the list.

“I did not want to cause problems; I wanted to win together. I did not dare to ask about being the first candidate,” she said. Rany added that she was busy as a new mother and did not push any preference for where she wanted to be on the party list for Brame.

She too was worried about Soeun’s chances. While he was a nice person, she said, he needed to push back against the authorities when residents were wronged.

“He is not brave enough to face the authorities. I am also worried about this,” Rany said.

She was aware of the charges against the five village residents and said it was unfair that farmers were advocating for their land but were instead being “abused.”

Sok Narim, who heads the Candlelight Party in Preah Vihear, said they had chosen candidates who were well-known and with local knowledge of the commune. He said there were some concerns over Soeun’s candidacy — Narim did not clearly detail who had picked the Brame resident to head the party’s list.

“If he wins commune chief but cannot resolve the people’s problems, then we will change him.

Soeun said he was working with Rany to rally support for the party and would work with residents to find resolutions to land disputes in the commune but would strategize on it after the June 5 election. “If I win, I will try to find the solution,” he said.

‘No Hope’

Son Savon is a defendant in the case alongside Sot. Savon is very much in the dark about the case, plaintiffs and charges against him. All he knows is that he asked the new people to stop tilling his land and he did it peacefully.

“I just said please stop, we need to resolve this first,” he said on Friday.

The February incident and ensuing case has robbed him of happiness, he said. He doesn’t know if a resolution is possible now — be it judicial or political, but he is willing to back anyone who says they will make this all go away.

“I do not think about which party because only an authority that is relevant can resolve it,” he said. “If a new candidate can win and resolve it, that will also be a good thing.”

Sitting under his stilted house in Brame, Sot is worried. He is scared the case might go to trial and there was little he could do with an “unjust court.”

Unlike Savon, who is willing to vote for any party or candidate that can end the dispute, Sot has close to no hope at all.

“I heard the Cambodian People’s Party announce on the loudspeaker that they will register commune land titles and improve people’s livelihoods. These are just their promises,” Sot said. “When they win the election they will not do as they’ve said.”

“And the opposite parties, they will not win the election.”

Additional reporting by Ouch Sony

Correction: This article previously mislabeled Thon Sot’s photo.