Last week on the western edge of Phnom Penh, a long, teal-colored curtain quietly opened to reveal a court chamber behind a curved wall of glass windows.

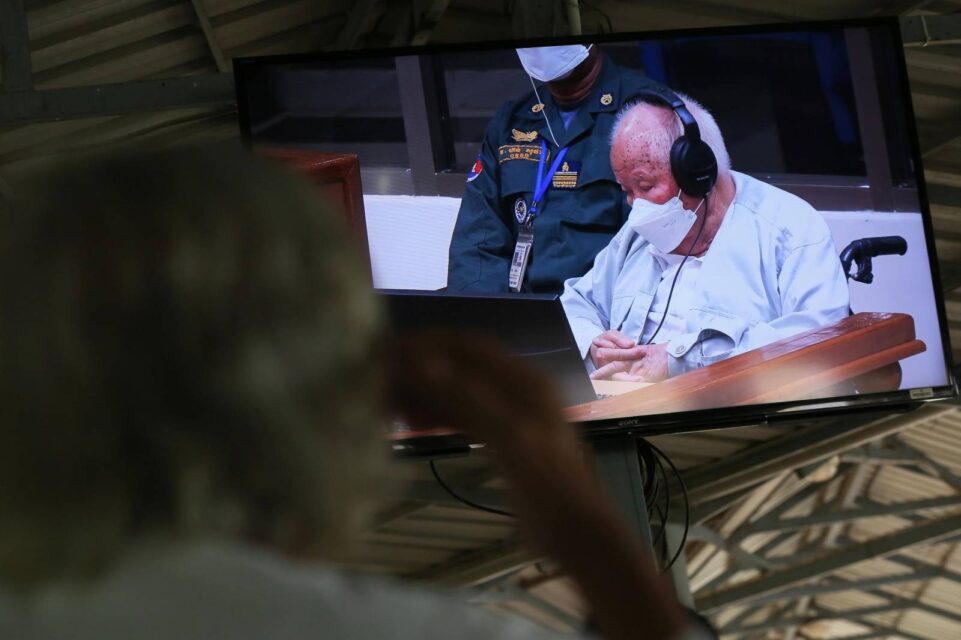

The judges within that chamber last Thursday looked out and down at the defendant, a frail-looking man slumped in a wheelchair. He sat flanked by court guards, facing the judges with his back to an audience gathered outside the windows behind him.

The man was Khieu Samphan, the former head of state of the Khmer Rouge. Already sentenced to life imprisonment on a slew of other convictions for crimes against humanity, Samphan went to court last Thursday to hear judges reject more than 1,800 points of procedural appeal that he’d hoped would distance himself from a government that oversaw the deaths of upward of 1.7 million Cambodians from 1975-79.

Samphan is now out of appeals, and will eventually be transferred from a holding cell in the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) — located in the Cambodian army headquarters on the edge of the capital — to an as-yet-unnamed facility in the national prison system. He is also the last-surviving Khmer Rouge leader tried by the ECCC, which brings its court mandate to an end.

A somewhat experimental effort with a $330-million price tag, the tribunal was set apart from others of its kind by a localized “hybrid” model that brought U.N.-sponsored legal teams to work with Cambodians in the national, French-derived court system. The ECCC has been met with mixed reviews over its time — from those bitterly disappointed to see so few Khmer Rouge members brought to court, to those who see the chambers as having carried out their mission while gathering a painfully detailed historical record of one of Cambodia’s darkest times.

“Me, personally, I don’t want to celebrate. I wouldn’t hold a glass of champagne and say ‘Cheers,’” said Youk Chhang, a survivor of the regime and the director of the Khmer-Rouge-focused Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-CAM). “If we celebrate the victory, maybe it will cheer you up, but we need to look at the reality.”

Youk describes that reality as one in which he estimates 5 million survivors are left to cope with their losses in whatever way they can. Though he sees merit in how the ECCC opened new chances for survivors to come forward to talk about their experiences, for the most part he speaks of the court in terms of missed opportunities. He’s more focused now on what will become of survivors.

“Many of them do not have access to health care, are very poor,” Youk cautioned. “Their stories will be lost, and this will contribute to attempts at social justice in the future.”

His perspective on the legacy of the ECCC is one of several heard by reporters in recent weeks as the tribunal’s casework drew to an end last week.

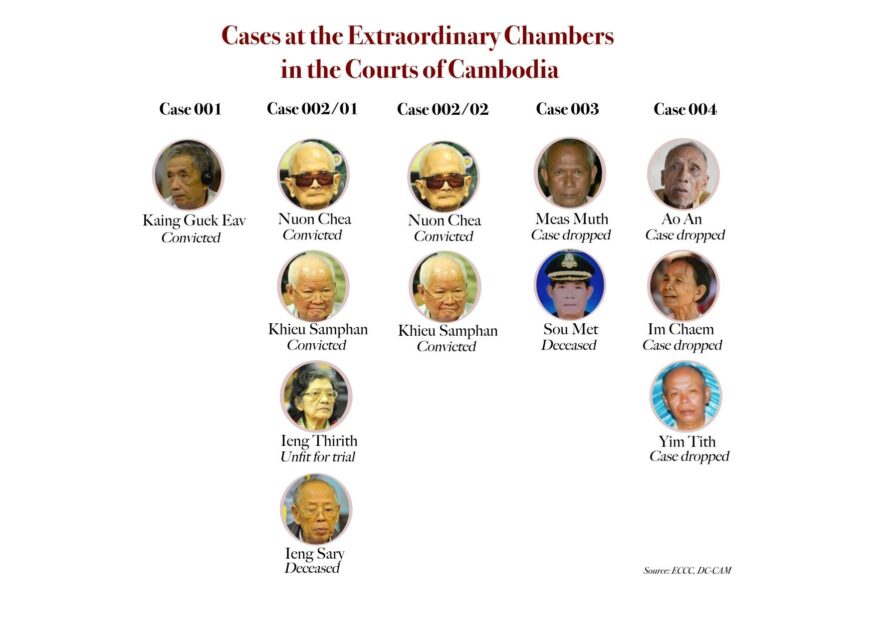

These proceedings have run in the background, often silently, for about 15 years. Over that time, the ECCC opened four mega-cases against a total of 10 Khmer Rouge leaders, with the court convicting only three of them.

Though the funding has been scrutinized in coverage of the tribunal, the cost was much lower than other tribunals led by the U.N.

These include those to try perpetrators of genocide in Rwanda, for which proceedings held in Tanzania cost roughly $2 billion over 21 years, producing 61 convictions; as well as for the former Yugoslavia, for which proceedings at The Hague cost about $2.3 billion over 24 years, for 91 convictions.

Looking forward, though the ECCC may have closed its docket, its final act will come next through a “residual phase.” Over the next three years, the tribunal will archive its massive evidence troves while winding down its support programs for survivors.

Of that population of millions, about 3,800 took part directly in the ECCC proceedings as civil parties who filed suit against former Khmer Rouge leaders.

“I couldn’t accept that so many of my family died at that time,” said civil party Kann Sunthara, explaining her motivation for joining the tribunal. “Every time I went [to court], I’d cry listening to it.”

Sunthara, 70, estimates she lost about 30 relatives during the Khmer Rouge era, including her husband, two children and brother. She spoke with VOD at her house in Kampong Speu province, where she lived with her late sister until her death about five years ago.

Originally from Phnom Penh, Sunthara was forced out of the capital by the Khmer Rouge after they conquered the city in 1975 and forcibly evacuated its population to the countryside. Sunthara spent the next years in Takeo province, working to dig canals. She says her husband was killed in a prison camp, while her brother and his wife vanished at S-21 security center.

It was in 1996 that Sunthara remembers a friend from a civil society organization asking if she’d like to file a criminal complaint against the Khmer Rouge.

After that, “the court asked me to participate with the others — mostly they’re other victims that the Khmer Rouge forced to labor and left to starve.”

On July 18, 2007, the ECCC co-prosecutors requested the judicial investigation of five suspects: Samphan, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, Ieng Thirith and Kaing Guek Eav, who was also known by the alias Duch.

These requests triggered a race against time, given the advanced age of the suspects by the time the investigating judges began their work.

Duch was to be investigated for his role as the leader of the security center S-21, where prosecutors accused him of torturing and killing prisoners under his watch. The court accepted this as Case 001 and, in a trial laden with symbolic weight, convicted Duch in 2010. After he appealed his original sentence, arguing it was too long, the Supreme Court Chamber increased it in 2012 to life imprisonment.

He died in 2020, at the age of 77.

The remaining four suspects were all implicated in what became Case 002, which was later split into two sub-cases. This second case includes most of the brutal legacy of Khmer Rouge policy, including acts of genocide.

Even still, the case produced just two convictions in Samphan and Chea, the Khmer Rouge general secretary said to be the movement’s “Brother Number Two” only under Pol Pot.

The other two suspects, the husband-and-wife Sary and Thirith, had been the regime’s ministers of foreign and social affairs, respectively. Sary died in 2013 at the age of 87 during court proceedings against him. Thirith was deemed unfit to stand trial due to worsening Alzheimer’s. She died in 2015, aged 83.

Chea, who maintained until the end that he had only acted in the best interests of the nation, died in ECCC custody in 2019. He was 93. Known as the chief ideologue of the Khmer Rouge, he died while appealing his own convictions for a slew of crimes against humanity.

These five were the highest-profile Khmer Rouge to be called before the tribunal, but they were not the only ones.

On September 7, 2009, two years after their first requests, the tribunal’s co-prosecutors officially named their last five suspects. These were Meas Muth and Sou Met, who respectively served as the heads of the Khmer Rouge navy and air force; as well as Yim Tith, Im Chaem and Ao An.

Those three were infamous cadres accused of waging brutal purges under the command of Ta Mok, the regime’s top military chief.

His nom de guerre translated to “Grandpa” Mok, but he was also known to Cambodians as “the Butcher” for his command of mass killings. His real name was disputed, but he was believed to have been born as Ung Choeun. He died in 2006, before he could be brought to trial.

The investigations of his men would be set under Cases 003 and 004. By the time court proceedings ground to a halt on these — stalled in the pretrial stage, caught between gung-ho international prosecutors and their reluctant national counterparts — they would come to symbolize what most saw as a hard line that the Cambodian government would not cross.

“This was going to be a model court, but it didn’t really live up to the expectations,” said Michael Karnavas, the international defense lawyer for Muth.

Karnavas, a U.S. national who has made a career in international tribunals, first worked in Cambodia in the mid-1990s as a legal development consultant.

Though he believes the ECCC leaves behind a considerable legacy, Karnavas saw the chambers as hobbled by a “schizophrenic” split between national and international perspectives of the court’s mission.

“In the end, with 003 and 004, the pre-trial chamber was unwilling — unable we should say — to make a decision, as the nationals and internationals would not agree,” he said. “There was a very bitter, I think, fight over the pre-trial chamber, lots of acrimony. And that sort of dampened the expectations of this tribunal.”

Political influence aside, Karnavas opined that the domestic judges, though knowledgeable of the Cambodian system, lacked the “depth of experience” to handle mega-cases; on the other side, he believed that the international judges were “were not as qualified as they should have been,” and were mostly unfamiliar with the French legal system used in Cambodia.

“The hybrid systems of other tribunals are much more efficient, but this court was of course based on a treaty between the U.N. and the Cambodian government,” he said. “Everyone had understood well in advance that this would be a cumbersome practice with built-in mechanisms either there by design or default that would cause a great deal of delay and even stalemate.”

Alex Hinton, a genocide expert who testified at Nuon Chea’s trial in 2016, had a similar view of the procedures with an overall positive outlook on the legacy.

“There’s been good, bad and ugly along the way,” said Hinton, who is also a professor at Rutgers University in the U.S. “In the end, I think commentators focus too much on the bad and the ugly and don’t focus much on the good.”

Hinton said the court’s convictions were no small feat. He also saw merit in rooting the court firmly in Cambodia to ensure its rulings had actual meaning for the public.

At the same time, he said domestic political interference in the courts made international participation a high priority. Though that’s common for tribunals of this kind, Hinton believed state control was especially visible in the ECCC.

“Governments always wield power in these situations, which is sort of the reality. Politics is present in this one more than most,” Hinton said.

“Where I land is, look, we could have not had a trial at all — or something very local, which, looking at the 1979 tribunal, wouldn’t have gone very well.”

***

Before the ECCC became fully operational in 2007, both victims and perpetrators of Khmer Rouge atrocities had largely been left to reckon with their experiences on their own.

A tribunal presented an opportunity for some structure.

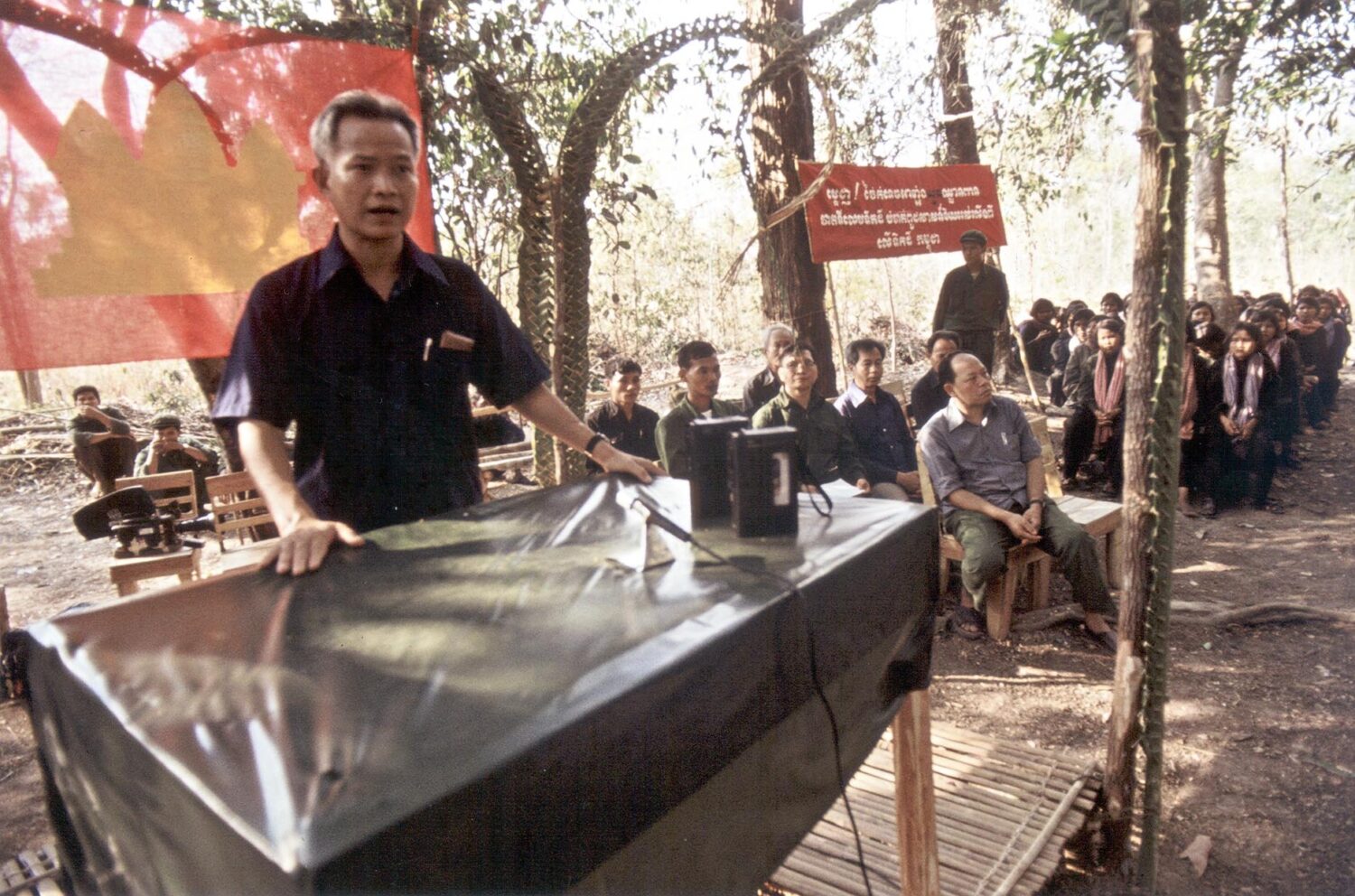

The first attempt at this came in 1979, as part of the immediate aftermath of the Vietnam-led military defeat of the Khmer Rouge in most of Cambodia. The Vietnamese stayed to oversee the formation of a new, single-party socialist state that swiftly outlawed the Khmer Rouge.

In the first trial, the People’s Revolutionary Tribunal — working out of Chaktomuk Theater in Phnom Penh — found Pol Pot and Ieng Sary guilty in absentia, sentencing them to death in what historians often describe as a show trial.

By 1996, Prime Minister Hun Sen had risen to the top of the government while the remaining Khmer Rouge dug in at Anlong Veng at the Thai border, under the leadership of an increasingly frail Pol Pot.

Looking to put an end to the Khmer Rouge once and for all, Hun Sen declared amnesty for members of the communist movement who surrendered and pledged their loyalty to his government in Phnom Penh.

This was to be his “Win-Win Policy,” which has since formed a central pillar of his political brand. At the time, it worked as intended. High-level defections included Ieng Sary, and the remaining Khmer Rouge strongholds in the borderlands quickly crumbled with a lack of troops.

Paranoia and internal division hastened the end of the movement. Ta Mok declared Pol Pot a traitor to the cause in mid-1997, ordering his troops to apprehend “Brother Number One.” Pol Pot died almost a year later under house arrest, allegedly by suicide.

The next year saw even more Khmer Rouge defections and, in 1999, the Cambodian military arrested Ta Mok on the Thai border. He had never made a deal with Hun Sen, unlike his former comrades, and the government imprisoned him in Phnom Penh.

As the Khmer Rouge evaporated as a military threat, Hun Sen turned his attention to firming up his consolidated power. At the time, he opposed bringing Samphan or Chea to trial.

“If the wound does not hurt, should we poke a stick into it and make it bleed again?” the prime minister asked. “If we bring the pair to prison … it could lead to renewed civil war.”

Still, there were other Khmer Rouge who were open game. Defiant, notorious and already in state custody, Ta Mok was an easy choice for the first suspect of a new tribunal.

But his day in court never came. Hun Sen and other Cambodian officials sought to try him entirely within the bounds of the national courts, a goal that led to grappling among themselves and with the international community.

“This is the pure Khmer solution,” Hun Sen argued in 1998. “If we use the right medicine for ourselves, we will be cured soon. But if foreigners add their medicine, it will continue to go on and on.”

Meanwhile, the U.N. voiced its concerns that a purely domestic trial could not meet international standards, given the undeveloped and politically fraught nature of the courts.

Disagreement between Cambodian officials — many of whom, including Hun Sen, had their own backgrounds with the Khmer Rouge — also helped keep Ta Mok imprisoned indefinitely at a military facility while negotiations with the U.N. finalized the ECCC.

In 2006, suffering from respiratory ailments, he slipped into a coma and died. The tribunal began in full the next year.

His absence placed him among a murderers’ row of Khmer Rouge who died before the curtain rose at the ECCC, and prosecutors designed Cases 003 and 004 in part to account for crimes Ta Mok had overseen. The grinding procedural debates of those cases lasted for years and sapped public interest in the tribunal.

“There’s always been a split — this issue has been very personal for a very long time, and so people take it personally, they want justice on their own terms,” said DC-CAM’s Youk of survivors. “Some think justice has been served, others have always said no. I think they need to come to their own terms, through support and other programs.”

The court has pledged to devote funding for the next three years to help survivors, including the civil parties. Though some survivors have sought mental health counseling with the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization, the main nongovernmental organization providing such help to Khmer Rouge victims, there are currently few resources targeted at this population.

As the years have passed, it has become increasingly difficult to track down the civil parties. People die, or move away. Some change their phone numbers or simply move on to the pressing issues of day-to-day life.

Before meeting with Sunthara, VOD called about a dozen numbers for civil parties provided by DC-CAM. Those calls either failed to connect, or were answered by people who said they didn’t know the people listed as civil parties.

Sunthara’s house in Kampong Speu is large and well-appointed, but she lives alone and worries about her livelihood in retirement. Her nephews, the sons of her late sister, built the home for their mother and aunt. They are her closest living family members.

She didn’t know about Samphan’s appeal until reporters told her, but seemed unphased by the news.

“They were convicted with life sentences, but I’m not entirely satisfied because they were never tortured as we were,” she said. “It seemed their lives in prison were very easy, unlike ours — whenever I saw them in the court, their clothes were really clean and they looked back at us with big eyes.”