SIEM REAP and PHNOM PENH — Sok Chamroeun was grilling fish at home the morning of March 11 in Siem Reap province when a stranger came asking if her husband Puth Thona was home.

Half an hour later, 10 provincial officials and police officers rushed into her house and arrested Thona within seconds, she said. Authorities gave little cause for the detention before they took her husband away.

But Chamroeun said she had guessed the reason behind the arrest.

“When they came for my husband, I knew that he was in trouble because of [his Facebook posts],” said Chamroeun, who lives in Slakram commune in the temple town.

Thona, a 32-year-old tuk-tuk driver, has shown his support for the outlawed opposition CNRP by sharing posts and videos online of senior opposition officials. Thona had posted on Facebook his apprehensions about the Cambodian government’s efforts to track and test for Covid-19, which by March had spread beyond China into most of Southeast Asia.

“Wait and see, if it infects my brothers and sisters, I will not let you off the hook,” he posted on March 5. At that point, Cambodia had only reported one positive case, a Chinese national visiting Cambodia.

Two days later, the Health Ministry reported the nation’s second case — and first Cambodian national to test positive — following the patient’s interaction with a Japanese man who tested positive after leaving the country.

Thona then took to Facebook again to mock Prime Minister Hun Sen’s statement during a speech in February that if coronavirus cases were detected in the country, then that month would have 31 days.

On May 21, more than two months after his arrest, Thona was convicted of communicating false information and sentenced to one year in prison.

Chamroeun and Thona had discussed his posts, with the tuk-tuk driver assuring his spouse that other Facebook users were posting similar comments and asked her not to worry.

“I told him ‘when you do anything, please keep in mind your wife and children,’” she recalled telling Thona.

Thona joined at least 30 people arrested, charged or convicted for allegedly posting fake news about the Covid-19 pandemic, according to international rights group Human Rights Watch (HRW).

The group has documented 13 people, most linked to the dissolved opposition party, who have been sent to pretrial detention on charges of “incitement” and “plotting.” Thona is the only detainee who has been convicted so far.

Three people face similar charges, but have been given bail, the rights group reports. Fourteen other Cambodians, including an underage student, have been asked to make public apologies and sign agreements with authorities to not publish “fake news” before being released from police custody.

The police have largely been opaque about the underlying evidence used to facilitate these arrests, with two police officers telling VOD that those who looked to “cause chaos” were jailed.

‘Not a Joke’

A majority of the alleged fake news related to Covid-19 was posted on Facebook, and, in some cases, arrests were based on private phone conversations or messages in private chat groups. According to HRW and other rights groups, the government and police have not explained how they accessed these private communications or how they qualify as fake news.

The underage student, who lives in Kampot province, had sent an audio message in a private social media group in March claiming that a few classmates had died and others were sick from Covid-19, according to a post on the Kampot Provincial Police’s Facebook page and the girl’s apology video.

The police questioned the 14-year-old and made her issue a public apology in front of her peers, which was also streamed on the Facebook pages of the provincial and district police. The student said: “I would like to point out to all the people on Facebook that this school has no coronavirus. So, I am sorry. This information that I talked about yesterday wasn’t true.”

The video and screenshots were first posted online in mid-March revealing the identity of the underage girl, and later her face was partially obscured behind a star emoji.

In Phnom Penh, Koy Sam Ath posted a video on March 6 reacting to news originating from Vietnam about the Japanese passenger who had departed from Siem Reap, testing positive for Covid-19 on arrival in Nagoya, Japan. The passenger has transited through Vietnam.

“We must appreciate yuon because they announced that Cambodia has Covid-19; if not, people across Cambodia would not know that Cambodia has Covid-19,” he posted on Facebook, using a pejorative for Vietnamese people.

“It is lucky that yuon shouted that Cambodia has Covid-19,” he says in the video. “If the ordinary people shout, they might be arrested.” Three days later, Sam Ath was arrested and sent to pretrial detention for alleged “incitement to commit a felony.”

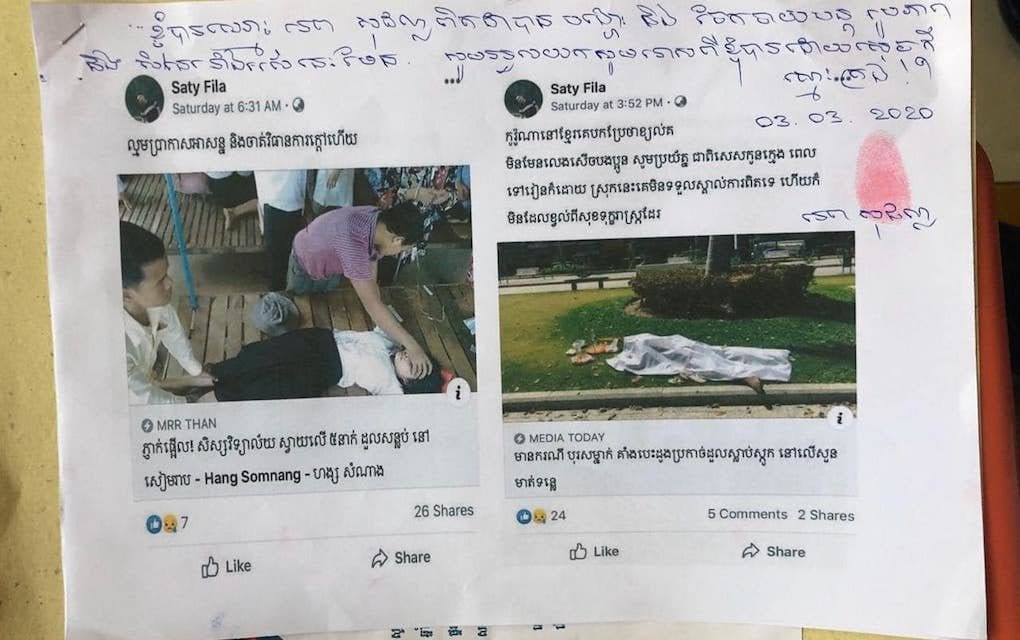

Tep Phalla, who goes by “Saty Fila” on Facebook, posted two articles on the platform, one about a high school fainting incident and the other about a person who had died of a heart attack, and claimed that the government needed to take urgent action to deal with coronavirus in Cambodia and that the authorities were likely obfuscating actual cases.

“Corona[virus] in Cambodia is portrayed as fainting. It is not a joke, brothers and sisters,” he posted. He was detained and questioned by Phnom Penh police, to whom he apologized for committing a mistake and disseminating “untrue information.”

Five people who were detained and released after making public apologies were reluctant to speak to VOD reporters for fear of repercussions from local authorities.

‘Fake News’ Used as a ‘Political Weapon’

Rights activists have said attacks on free speech and the muzzling of the media in Cambodia has created an air of fear, with many Cambodians choosing to temper their views.

Cambodia does not have existing legislation to deal directly with fake news, but Hun Sen directed officials in 2019 to begin the drafting process. So far, existing Criminal Code provisions have been used to charge people allegedly spreading fake news, even though the code does not contain a legal definition for this alleged infraction.

On Thursday, Information Minister Khieu Kanharith told reporters that new legislation was unnecessary because it would be difficult to exactly identify what constituted fake news and could infringe on Cambodians’ right to free expression.

He added that such a law would not be in the larger public interest, but did not comment on people who had been arrested in the past few months for allegedly spreading fake news.

Phil Robertson, HRW’s deputy Asia director, said these charges were aimed at silencing critics of the government, especially during the pandemic, which has caused severe economic distress among Cambodians.

“Like so many other things, the charge of ‘fake news’ is used as a political weapon by Hun Sen and the [ruling] CPP against critics who they decide are too troublesome and must be taken down,” Robertson said.

This trend was not unique to Cambodia, he added, with similar arrests reported in the Philippines, Thailand and Malaysia to suppress dissent about job loss, loss of income and economic insecurity.

“The reason is these governments worry that any line of critique or expressed dissatisfaction with the government can balloon out of control, taking advantage of people’s anger with job losses, shuttered companies, and loss of income and economic security,” he said in an email.

However, Huot Sothy, the Siem Reap provincial deputy police chief involved in Thona’s arrest, said the tuk-tuk driver’s Facebook posts were not free expression, but instead intended to cause “public security” issues. Thona’s posts combined had about 150 likes and 30 shares on Facebook.

“Fake news causes chaos and impacts public order in society and causes fear,” he said.

The Siem Reap police officer was candid about provincial police teams monitoring and surveilling Facebook accounts to quickly counter alleged fake news. Asked why some people were let off with warnings whereas others faced charges carrying up to two years in prison, Sothy said the court determined which communications constituted a crime.

“I do not know. This is the court’s handling of the case because if the court sees there is a crime, the court presses charges,” he said, referring to Thona’s case. “If there was no crime, the court would not do it.”

National Police spokesperson Chhay Kim Khoeun echoed his provincial colleague in noting the need for social media surveillance to tackle “ill-intentioned and manipulative” people.

The senior police official advocated for citizens to self-censor if they are concerned about the police monitoring their online activity.

Rights advocates have routinely said that arrests related to public expression of opinions in Cambodia can have a chilling effect on the public, causing people to be weary of freely expressing themselves.

“If you have the right to post [online], we also have the right to monitor your posts,” Kim Khoeun said. “If you say we silence your rights, you should stop posting.”

The targeting of those expressing dissatisfaction with the government was on display on July 14, when Hun Sen threatened a Banteay Meanchey resident who he identified as “Rath Sothy.”

Rath Sothy, according to the premier, allegedly said foreign funds were being used to make cash transfers to the poor who were facing income loss because of the global pandemic.

“I would like to say to Mr. Sothy, you are lucky that I did not order your arrest,” said the prime minister at a speech in Prey Veng province. “On that day, if I had ordered your arrest, you, Mr. Sothy, would be in prison now.”

VOD could not reach Rath Sothy, and Hun Sen claimed that the man had fled to Thailand.

An Unexpected Arrest

In late March, Ouk Chanthy received a call from her husband Yim Sareth, a construction worker in Dangkao district’s Choeung Ek commune. He told her that he was being arrested at his worksite. That’s all Sareth said before the call was disconnected, she recalled last week.

It wasn’t until later that evening that he called again to say he was being sent to pretrial detention for alleged “incitement to commit a felony” linked to a Facebook post he had published days earlier. Prior to the CNRP’s dissolution in 2017, Sareth was the first deputy commune chief for the opposition in Svay Rieng province’s Chantrea commune. He was also charged with “plotting,” and now faces up to 12 years in prison on both charges.

“I never expected this. It is too far-fetched,” Chanthy said, visibly upset.

When she met him at Phnom Penh’s Prey Sar prison a few days after he was detained, there was more clarity over the cause of arrest. He had posted a photo of himself on March 20 with a caption.

“I am wearing this mask because I don’t want to inhale dust and cement, especially Covid-19,” read the caption.

Police officers showed Sareth a printout of this post when they arrested him at his construction site a week later, according to Chanthy. The garment worker said the father of three had routinely asked his children to wear masks to protect themselves from the virus, but she never believed that this would be perceived as incendiary.

“There is no freedom in our country,” she said. “We talk but they want to silence us.”