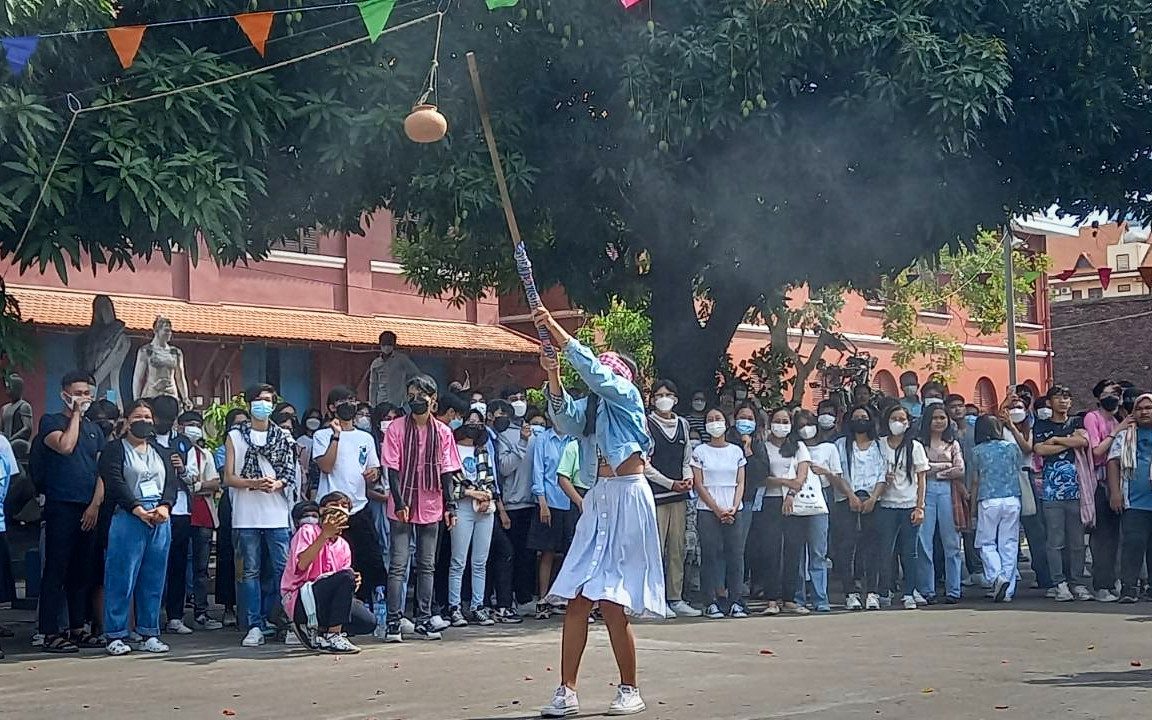

The sound of music and laughter rose over the courtyard as a trio of blindfolded students carefully poked with long sticks to find the clay pots hanging overhead.

Part of a traditional Khmer game known as veay ka’am, the pots were filled with a mix of 1,000 riel notes and lightly scented baby powder. The blindfolded students were out to break the pots, and as they alternated between feeling for them and lashing out, a crowd of students cheered their encouragement — from a safe distance.

The students were locked in friendly competition as part of a Thursday gathering to celebrate Khmer New Year at the Royal University of Fine Arts. Though the official new year’s day is next week, the students at the school have marked its approach with celebrations and traditional activities.

For many, these Khmer games, dances and songs are a highlight of the holiday season.

Soeut Sovany, 24, and a member of an event organizing committee at the arts university, told VOD the school typically made a big celebration and exhibitions for the students to mark the new year. But due to Covid-19, the students had a long wait before such festivities returned to campus.

“I am very happy when students gather to play these games,” Sovany said at the Thursday event. “We never abandon this kind of tradition. One more thing we never forget is how to play our popular traditional games, even dancing, so people can have a fun moment together.”

This year’s Khmer New Year is likely to be an especially festive one, as the country reopens after a yearslong quiet spell during the pandemic and its era of public health restrictions.

Phnom Penh City Hall issued a statement on April 4 urging residents to maintain security, safety, and order during Khmer New Year. The statement approved the playing of Khmer traditional games, though it discouraged some traditional activities that could put motorists at risk.

“Participate in all kinds of popular games and absolutely avoid throwing water, charcoal powder, and beating passengers while they are driving and riding a motorbike to chase each other,” the statement said.

Luckily, the games on offer at the arts university were of a simpler variety.

Sovany said there were more than 10 games organized for the school’s Khmer New Year events. Besides breaking the pot, students also organized a tug of war (known in Khmer as teang prot), a fruit-eating competition and several other games familiar to students from around the country.

Sovany said she had grown up playing these kinds of games at a pagoda in her hometown in Banteay Meanchey province.

“It’s a kind of unity. Students can play [together] in a group,” she said. “My village still plays our traditional games. It’s not lost.”

Hin Sina, 21, a student at the art school, joined the Thursday celebration, known as a sangkran. A native of Phnom Penh, she said her school was the only place where she played such games while growing up.

“I never played when I was young in the village, only the program at school, because no one organized in my village,” Sina said.

For professor Sambo Manara at Paññāsāstra University, the meaning of Khmer New Year is providing a new step for people to reflect on their actions and rethink their life.

However, Khmer New Year is also the time for offering old people hope for a good fate.

“Khmer New Year is the new change from the old year, in which we ended life’s mission for the old year,” he said.

Manara recalled his own childhood and said that people typically prepared celebrations as long as two months before Khmer New Year. That time included traditional games, the professor said, listing off the usual favorites.

“The most popular is bos angkunh, leak kansen,” Manara said.

Both games would be known to villagers and are simple to learn.

Bos angkunh involves two teams lining up five hard brown nuts, then backing up and throwing another nut at the row. However, players must avoid the middle nut until the end, hitting it last.

If players hit the middle nut before the end, they receive a gentle punishment — a small rap on the knee with two nuts held together to make a sharp cracking sound.

Leak kansen involves a group of up to 20 people sitting in a circle. One player, armed with a krama wound tightly until it becomes short and stiff, chases another around the circle, trying to hit them with the krama. The player being chased flees from the light beating until they reach the empty place in the circle left by their pursuer, who then chooses a sitting player and hands off the krama by dropping it beside them. Once they drop the krama, the player takes up the role of the pursued, fleeing from their own beating until they can sit back in the circle.

Though such games are still familiar to Khmer youth, according to Manara, much of the game traditions have been lost. Besides sangkran programs at pagodas and other centers, he believed people rarely gathered on their own to play.

“It is just acting too. I can say that it isn’t from the heart,” Manara bemoaned of the modern lead-up to the Khmer New Year, adding that young people seemed to prefer drinking and singing to playing games. “For my generation, we did not act, we waited until the time came and played. This is a loss of their passion, heart and perspective.”

Manara said the loss of tradition was a social shift brought about by different factors. He named the pandemic as one reason, but also a state of financial crisis for many Cambodians as well as social issues facing youth, such as drug usage and lack of education.

“We have more good human resources than in the past — but why in the past did we have a good social order? Because of our family, pagoda and our general society,” he said.

Youths who spoke with VOD shared a similar sense of nostalgia for the games of their early years.

Morth Theara, a 22-year-old university student from Phnom Penh, told VOD how much he missed playing traditional games during Khmer New Year.

Theara remembered being a teenager in the city, playing bos angkunh, tug of war, and another game called choal chhoung, which involves throwing a balled-up krama between two teams who must catch the scarf while singing improvised, mocking songs about the opposing players. He said he and others from the village came together to play, sometimes on the road in front of his house.

However, similarly to Manara, he believed the spontaneity of these gatherings had been replaced by organized, agenda-driven events.

“I really miss it,” Theara said. “We have a good connection in the village. I miss that memory of childhood. But the younger generation isn’t like us.”

Theara thought people were more likely to go dancing, which he saw as capturing a similar feeling but without traditional meaning.

“It’s not so different. We have the same happiness and enjoyment, but the value is lost. We don’t really care about the culture and foreign influences like EDM [electronic dance music] dancing, water guns, throwing powder. Those are easy and people are likely to go along with those kinds of play.”