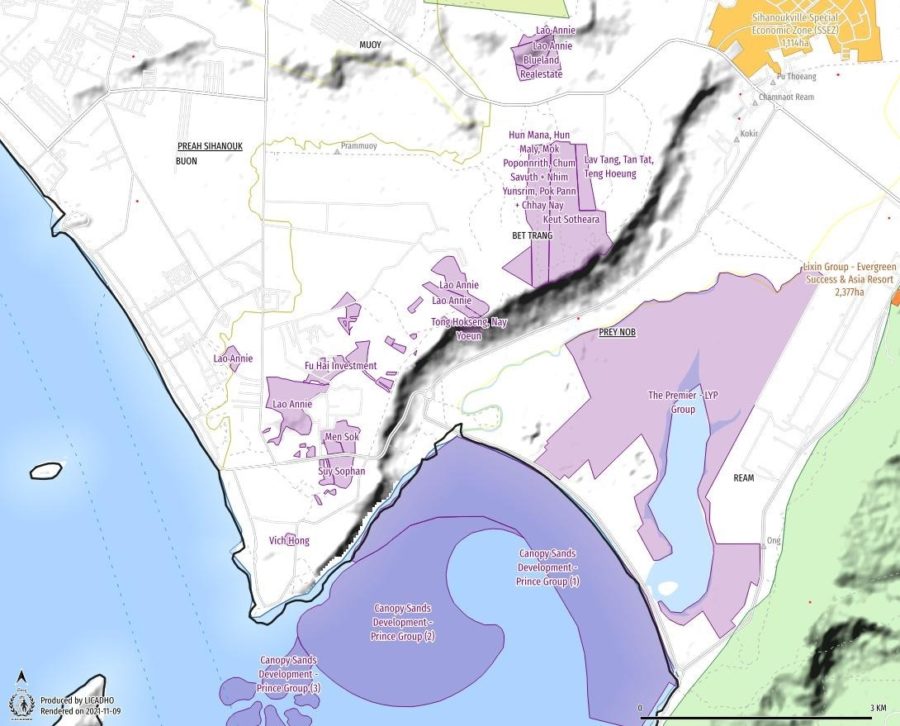

To one side is state land Prime Minister Hun Sen recently transferred to his daughters. To the other is land given to a three-star general in Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit recently promoted to be his assistant, as well as to a notorious tycoon, the late Suy Sophan.

Lao Annie, who heads several real estate companies in Cambodia, according to company records, said on Tuesday that she was “shocked” when she read news about all the important people who had land near her in Preah Sihanouk.

In the latest release of government sub-decrees, she received two more plots in Bit Traing commune, in Preah Sihanouk province’s Prey Nob district, totaling 23 hectares. Monitoring by rights group Licadho shows four other plots in the district granted to Annie, and another to her company, Blueland Real Estate.

But Annie said she was not involved with, and was unaware of, the powerful people who had land around her.

“I was shocked because I saw all the big names and I see my name with all the big names. That scares me, because I’m living here alone, without my husband, and I try to be low key,” Annie said. “And then when I see my name I was really shocked. I’m nobody. I had the chance to buy the land a long time ago.”

She bought the land almost 20 years ago, when everything was measured by hand. Now, local authorities were undertaking more precise measurements, and her lawyer was handling the transactions one-by-one to receive formal titles, Annie said.

There was no exchange with the state to receive the land, she said.

She was born in Cambodia but had lived abroad. She was recently divorced, and the land had been bought by her husband’s money, she said, though she declined to give specifics about him. She had mostly been a housewife, though now she renovates properties, she said.

“All that land, for me, according to my vision, should be residential,” Annie said. Sihanoukville had the casinos, and though there were some condominiums around, there were “not enough nice houses,” she said.

Plans were uncertain due to Covid-19, but “I would like to develop it later,” she said, adding that the area still needed infrastructure like roads and streetlights. “The city is quiet. We’ll probably wait till next year to see how things are going.”

Annie provided a contact for her lawyer, Rath Sotha, who declined to comment, saying the work was confidential.

A Koh Kong provincial administration post from two years ago says authorities stopped illegal construction by Annie on Koh Sdech island.

Last year, Hun Sen ordered a land privatization drive to hand titles to people who had long-standing claims to state land, emphasizing the needs of poor families.

In practice, however, recent land disputes have largely involved overlapping claims to state land, with residents saying they were being pushed out for private or state development projects.

In Phnom Penh’s Boeng Tompun area, the houses of about 10 families who said they had lived in the area for 20 years were demolished in August.

One resident, Sary Yuthipol, a soldier, said at the time that they were being forcibly evicted without compensation.

“I’ve always raised my hands to beg for all development, [but] if there is impact, please give compensation,” Yuthipol said in August. “We are not illegally encroaching the land. We have been living here since 1991 and authorities have recognized it.”

Another resident called the state evictions “theft.”

Meanchey district governor Pich Keo Mony said at the time that authorities had not compensated the 10 families because they were living on state land illegally.

“State land has no compensation,” Keo Mony said.