POIPET CITY, Banteay Meanchey — Since just before the pandemic started, Chhoum Phen has changed his job more than five times within Hi-Tech Apparel, the garment factory he has worked at for more than five years.

The worker, from Banteay Meanchey province, said he realized the moves were punitive when a manager offered him a higher-paid role as a sewing line leader or supervisor if he dropped his union membership.

Hi-Tech’s compliance manager, Chanra Seng, has denied that there was any intimidation of the union, saying the company respects the freedom to associate: “I, as a compliance officer at the company, conducted this education directly from my experience, having participated in many education [sessions] with the ILO and working well with the factory ILO advisor.”

Phen, who joined the union after a stint as a factory-approved shop steward — a role he found had no real power — said he was committed to carrying the union forward. He said his peers are the only unionized workers within the Poipet O’Neang Special Economic Zone, where Hi-Tech’s Thai owners are offered trade benefits and access to a low-cost workforce.

“The manager wants us to dissolve the union in the factory, but for us we’re still willing to do it,” said Phen.

Cambodia has opened its arms to foreign businesses through special economic zones, which grant investors open space, lucrative tax incentives and a relatively cheap labor force. As these zones expand, unions are attempting to access the factories behind SEZ gates, with workers saying labor compliance sometimes falls by the wayside in spite of higher salaries for SEZ workers.

Cambodia’s SEZs have historically proven a challenge to unionize, said Heang Vannara, an organizer for labor rights group Central based in Siem Reap province, also in the country’s northwest.

“There’s higher security inside the SEZ,” he said. “There are security guards surrounding [its gates] … and the reason they do that is because many of them do not follow, are not compliant” with Cambodian Labor Law, he said.

Employers inside zones are known to threaten or terminate workers who lead unions, he said, but they’re often failing to provide proper health and safety conditions to their employees, he said.

Even though the workers realize they’re working in improper conditions, the combination of the secure gates, threats from managers and lack of access from labor advocates prevent workers from taking action, Vannara said.

“They’re all so scared because many are illiterate, they don’t have high or medium education,” he said. “The manager level can easily intimidate them and track their location.”

Investor-Friendly Offerings

At the end of a typical rural road, flanked by small shops and an open-air market, a concrete wall rises from an empty field, where a few cows mill about the tall grasses. Inside those gates are the Poipet O’Neang SEZ and factories owned by Thai and U.K. nationals, which are producing garments, packages and light machinery around 20 km from the border of larger manufacturing hub Thailand.

The Cambodian government introduced SEZs with a similar attitude as it did for economic land concessions, or large land grants given to foreign and local companies on 99-year leases: entice companies, especially foreign investors, to develop Cambodia’s land and economy at the same time, with few regulations.

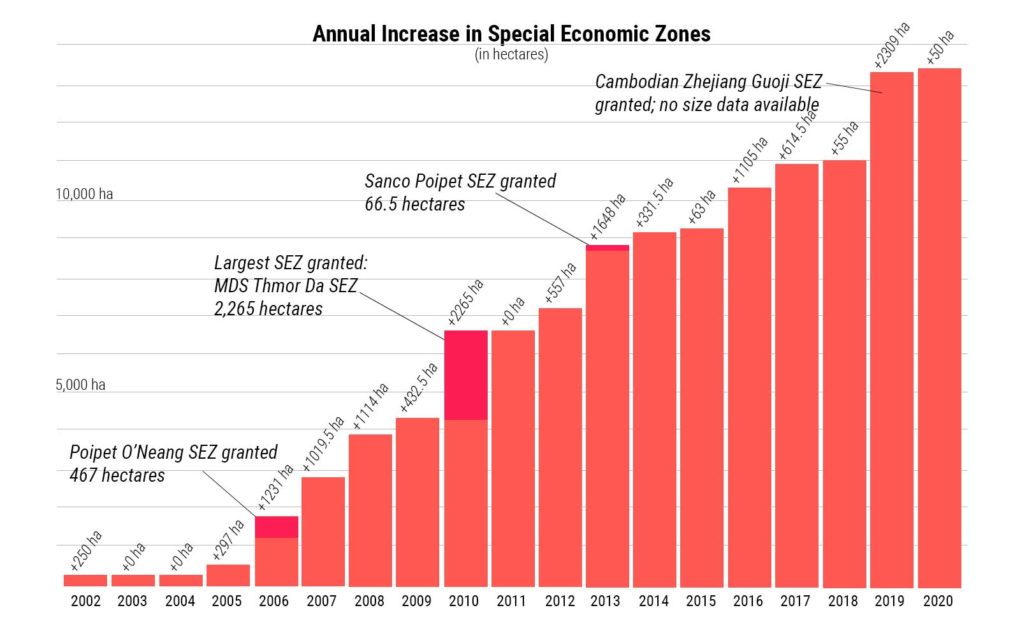

ELCs came under fire for the clearing of forests outside their boundaries and abusing residents who live in and around them. Though the government canceled the ELC program in 2012 and rescinded some concessions, SEZs have increased in recent years.

After approving its SEZ policy in 2005, Cambodia had approved 21 proposals for zones across the country by early 2009, according to archived documents from the Council for the Development of Cambodia. At that time, SEZs were viewed as a way to bring manufacturing from international developers, and all the jobs it creates, to Cambodia’s rural corners.

Cambodia has granted more than 13,300 hectares of SEZs since 2002, still a small fraction of the 1.2 million hectares turned into economic land concessions in their heyday between 1996 and 2012, according to data collected by Open Development Cambodia.

One of the largest is tycoon Try Pheap’s MDS Thmor Da SEZ in Pursat, which has been accused of housing scam operations with enslaved workers.

The CDC offered a number of trade incentives in order to lure international developers onto Cambodian land. New factories in an SEZ can get a tax holiday of between six and nine years, and foreign investors don’t need a local partner, which is a requirement for land ownership and business operations elsewhere in the country.

Investors are also told by the CDC that they can access tariff-free exports to the U.S. and E.U. because of Cambodia’s status as a developing country in lucrative trade deals: the U.S.’s generalized system of preferences and the E.U.’s “Everything But Arms” deal. However, the former has been under review by the U.S. trade department since it expired in December and the latter was partially revoked in 2020 due to concerns over rights violations in Cambodia.

Within an SEZ — which is often owned by Cambodian nationals or a joint venture with Cambodian and foreign partners — factories also get on-site approval, permitting and other government rubber stamps through a “one-stop service” office, unique to these trade zones. The CDC in 2009 also said these zones would be along major roads and have power plants specifically for their businesses in order to facilitate transport and production respectively.

Though Cambodian officials have focused on the benefits an SEZ can offer investors — and relations with a country as a whole — deputy prime minister Hor Namhong once said the zones should also lead to better labor conditions.

SEZs have spread across Cambodia, with nearly 40 developed between the passing of the law in 2005 and 2018 — and compared to more industrialized neighbors Thailand and Vietnam, this rate of development is high, according to a report by Bui Thi Minh Tam, a senior lecturer at Thailand’s Srinakharinwirot University. But she notes that location is generally more critical to the success of an SEZ than any tax benefits, and even if so, it takes five to 10 years for companies and employees to see the true benefits of their investments.

Unsafe Environment

Though Cambodia is still reliant on light manufacturing like the garment and footwear industry, foreign-invested heavy industries are starting to move into SEZs. Economists have long been calling for Cambodia to find ways to move up the value chain. But without adequate protections in place, heavier industry can also bring more safety risks, said one worker inside another Poipet SEZ.

Gneik Touer, 31, says he works a 12-hour night shift at the motor component manufacturer SC Wado at the Sanco SEZ, amid high-temperature machines. Touer said he bought his own helmet and gloves for handling the metal parts as he inspects and moves them between machines.

“I only got a uniform from the company. But it’s not personal protection equipment, even though [the machines] are 700 degrees in my section of work,” he said.

Touer said the company is often pressuring him to work overtime, and when he turns in a request for leave, his supervisors deride him as lazy.

“I myself sometimes want to quit because I have difficulty accepting impolite words and bad behavior from the manager,” he said.

He said he usually accepts the overtime, even though his wife gave birth to a daughter in November and he has to travel to Siem Reap to visit them. The company has no union representation so far, and Touer said he feels the risk is too high to exercise what he believes are his labor rights.

“I sometimes want to go and tell the company what they should do to follow the law, but I’m so afraid that when I tell them, by the end of the year I’ll be one of the workers whose contract is not renewed.”

A representative for Sanco SEZ initially agreed to answer questions from a reporter but never sent responses.

Any*, a worker at CamPack, a packaging factory in the Poipet O’Neang SEZ, said that after seeing workers in Hi-Tech mount the first unionization campaign inside the SEZ, he wanted to help lead his colleagues in forming their own. He and Thida*, another CamPack worker, said they’re still rallying colleagues to join a union before revealing their effort to the company. *The two workers asked to use pseudonyms to protect their jobs in the interim.

Holiday pay was an immediate issue for the workers, Any said.

“We think it’s not fair for us because on public holidays, if we come to work we’re supposed to get extra, but in this case we don’t get extra,” he said.

Thida said she was committed to organizing as she has some health and safety concerns at the company. She frequently uses a strong packing glue while assembling packages, and she says the noxious smell makes her dizzy.

The bigger issue, they both say, is the control by their Thai supervisors, who they say don’t listen to their needs.

“I want to have independent thinking among workers, that we don’t need to follow what employers want us to do,” Thida said. “We should try to do something if we think it’s the right thing to do.”

Dealing With Discrimination

Though union members at Poipet O’Neang SEZ’s Hi-Tech Apparel say they gained better worker benefits and easier rights to leave after unionizing, they still feel the company resents their presence.

Men Ratha remembers her supervisors as being more punitive when she joined the company in 2013.

“Back then, the supervisor and line leader, they were more aggressive, they were using impolite and insulting words, comparing us to animals,” she said. “Before we had a union, if we refused to do overtime one day because we’re busy [at home], we don’t want to do overtime, then we would lose the ability to do overtime for a week.”

Since she helped establish the union and became treasurer, Ratha said she had been able to help workers request vacation time and settle disputes with supervisors, but she felt the factory had taken advantage of the union’s situation.

It can be hard to recruit workers too, she said, as sometimes the union isn’t able to negotiate what the rest of employees want, referencing a dispute over Covid-19 quarantine and pay they encountered last year. Seng, Hi-Tech’s compliance officer, said the conflict, ensuing from a partial shutdown after one vacationing worker contracted Covid-19, was complicated but in the end most workers did not appear to want to follow the union’s argument.

“It was a bad look for the union because we couldn’t really ask for better benefits for workers for their livelihoods,” Ratha said.

Chanra, the compliance supervisor for Hi-Tech, said he thought the union was good for workers, but noted Hi-Tech already had shop stewards, or employees tasked by the employer to raise concerns in the factory, before the union started.

“Sometimes there are a few union issues when they go beyond the labor law. But we can solve it by meeting with the unions to find a legal solution [with] each other,” he said.

Sithar, a newly-recruited activist among the Hi-Tech Union, who did not want his full name used out of concerns for losing his job, said he had witnessed discrimination from Hi-Tech supervisors only after joining the union, but he’s also come to understand how workers can collaborate to secure better benefits.

“I took a longer time before deciding to become a union member and activist,” he said. “I had a lot of questions, and had a lot of doubts because the union took money from members … but then [union organizers] explained and answered questions, and now I trust them.”