On the evening of June 4, 2020, Sam* was in his Phnom Penh apartment when a worker in the building ran up to his door and told him: “Big men took the man with glasses, Tar, into a car. They had guns.”

“Tar” was the nickname used by Wanchalearm Satsaksit, a well-known Thai political activist who had been living in the same riverside high-rise before he was allegedly abducted earlier that day on the street below. Human rights groups have recognized him as Thailand’s ninth victim of enforced disappearance since the country’s current leaders staged a coup against the government of Yingluck Shinawatra in 2014.

Finding no trace of Wanchalearm in or outside the building on the night of June 4, Sam then told a neighbor to make a call, not to local police, but to Khliang Huot, an assistant to Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen. Huot was also governor of Chroy Changva district, where the condominium complex, known as Mekong Gardens, is located.

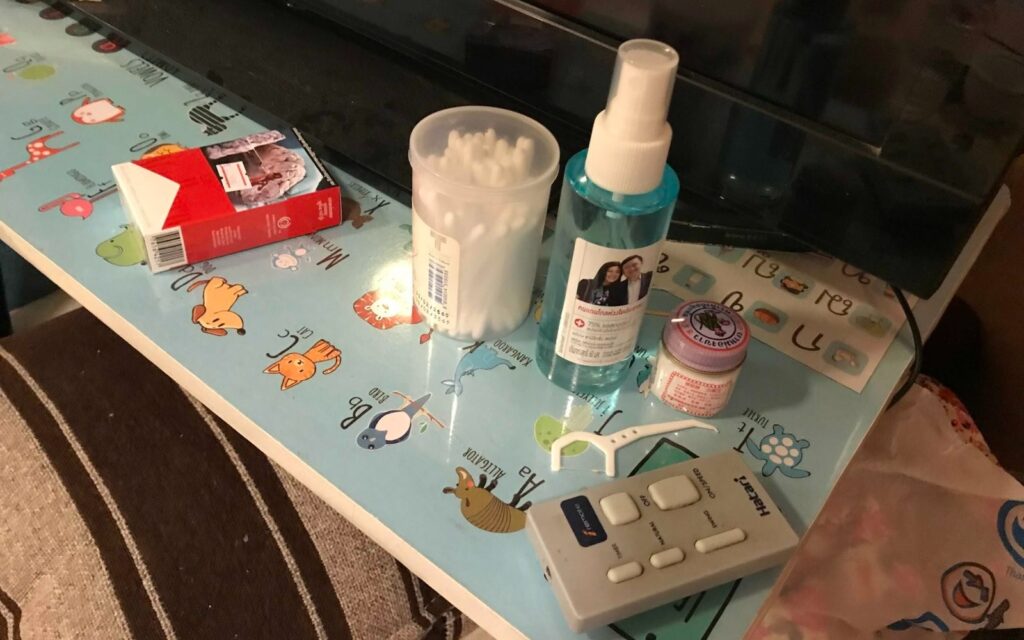

A few hours later, several men wearing plainclothes — Sam says they may have been Cambodian police or military — arrived at Mekong Gardens and entered Wanchalearm’s unlocked apartment.

One of the men, who were all known to work for Huot, instructed three building residents to gather any important items — electronic devices and documents — from Wanchalearm’s room, two sources said. The three residents complied, collecting the items for Huot’s men.

After the alleged abduction, Thai exiles living in Cambodia scrambled to avoid being exposed and potentially becoming the next to go missing. Ben*, an old friend of Wanchalearm who was in Thailand on the day of the suspected enforced disappearance, received a series of calls from several Thai exiles living in Phnom Penh asking him what they should do with Wanchalearm’s belongings.

Ben and the exiles believed his friend’s devices contained personal information about other Thai dissidents whom Wanchalearm had helped or communicated with. Five other Thai dissidents had disappeared from Laos in recent years, and Ben said he and others feared the information on Wanchalearm’s devices could lead to further disappearances in Cambodia.

“Everyone called me asking what they should do,” Ben told Prachatai and VOD. “I and other exiles knew that Tar was the one who helped take care of the others. …Hence, there must be a lot of documents [in there].”

“At first, I told them to destroy [Wanchalearm’s things],” he said. “They asked me how. One of them said to throw them into the Mekong River, behind the building. But out of fear of them being retrieved, I said the irretrievable way is to burn them.”

The quick decision to conceal evidence of Wanchalearm’s life in Cambodia is one of the many ways the activist’s history has been obscured over the last two years: an investigation by Thai authorities has stalled, and Cambodian authorities say they have “finished investigating” the case — despite remaining questions about a CCTV video showing a Toyota Highlander SUV tearing away from Mekong Gardens, purportedly with Wanchalearm inside; and Wanchalearm’s supposed Cambodian passport and bank account under the same Khmer alias Sok Heng.

However, this alleged destruction of evidence also sheds light on hidden aspects of Wanchalearm’s life beyond his public persona as an online political satirist. Interviews with several of his friends, neighbors and former colleagues, and social media photos, reveal his direct links to political elites in both Thailand and Cambodia, as well as his critical role in the secretive network of Thai political exiles in Cambodia, some of whom believed Wanchalearm possessed information that could put their own security at risk.

According to Sitanun Satsaksit, Wanchalearm’s sister, if there had been no foul play behind his disappearance, “there would be no need to clear out the room. There would be no need to destroy his things.”

“Everything around Wanchalearm’s case triggers an alarm bell that this is seriously wrong,” said Sunai Phasuk, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch. “There is cover-up, there is diversion. Whoever is involved in the case is powerful enough to come up with this total cover-up that will not allow the truth to see the light.”

Supporter of Thai Exiles

Wanchalearm was one of dozens of Thai political activists to be summoned by Thailand’s military council, led by current prime minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, which ousted the government of Yingluck Shinawatra and her Pheu Thai Party in a 2014 coup. Rather than turn himself in or await arrest, Wanchalearm fled to Cambodia.

Soon after arriving, he began to make friends among wealthy and politically connected Cambodians.

“He can befriend anyone,” Ben said, “from villagers to elites. … That’s the kind of guy he really was. When people got to know him, they loved his character and brought him out to drink and to talk business.”

Because of his connections, other Thai dissidents who were wanted by the military junta sought his help escaping into Cambodia. According to Ben, Wanchalearm gave them advice on where to cross the border and how to disguise themselves.

After a few years living in Cambodia, when many Thai exiles were coming to terms with the possibility that they would not be able to return home anytime soon, Wanchalearm came up with a plan to invest in various businesses that could support the exiles’ livelihoods, Ben said.

One business was a Thai papaya salad shop, which Wanchalearm opened near Mekong Gardens as a way to both employ and feed some of the Thai exiles living there. Kyle*, a Thai dissident who lived in Mekong Gardens, says he and several other exiles worked at the restaurant to keep busy and supplement the allowance provided by Khliang Huot, the then-district governor. Kyle recalls Wanchalearm being the business’s primary source of funds.

A month before Wanchalearm disappeared, Kyle said a tall, thin man started appearing on the footpath opposite the restaurant every afternoon or evening, never coming inside to buy food. Kyle did not recognise the man, and no one in the restaurant spoke to him. With few customers, they temporarily closed the business about a week before Wanchalearm disappeared, and Kyle never saw the man again.

On June 2, 2020, two days before Wanchalearm’s alleged abduction, Kyle also recalled preparing a noodle recipe for the restaurant when Wanchalearm sent him a message saying he was stressed out.

“I may have a serious problem, a bad problem. But don’t mind it. I will help you with the noodle shop every day,” Wanchalearm wrote.

Kyle never asked him for details about the problem.

On June 4, at around 4 p.m., about an hour before Wanchalearm was allegedly abducted, Wanchalearm sent Kyle a noodle recipe and made a joke about the name of the dish. He also mentioned he was struggling to get a loan from a friend to support one of his business ventures.

That was the last Kyle heard from Wanchalearm.

Governor’s Drinking Buddy

On June 18 this year, Sitanun posted a photo of her brother standing next to an older man in front of a body of water. The photo shows the two men smiling, holding up crabs to the camera. The man is Khliang Huot, the former governor of Phnom Penh’s Chroy Changva district; five sources have identified Huot as a handler of Thai exiles who fled to Cambodia following the 2014 coup. Multiple sources said Huot met Wanchalearm for drinks several times a year.

Kyle, who met Huot after moving into Mekong Gardens, said the official helped Thai exiles find housing in Phnom Penh, paid them an allowance, and took them out for meals and drinks.

When Thai exiles got sick and went to see a doctor, “the director would take care of us and pay our bills if it was a major case,” he said, referring to Huot.

Ekapob Luara, a Thai exile who is wanted by the Thai government for allegedly insulting the monarchy, lived in Cambodia for several months in 2014. He also said Huot covered his food, internet and housing. However, Ekapob said these benefits came with conditions: he was only allowed to spend a limited number of hours outside the accommodations Huot provided, and other Thai exiles would regularly check his phone to make sure he had not shared the location of his accommodations with anyone.

“I didn’t have to do anything. People gave me food. There were people giving me money. But there was no future,” Ekapob said. “It may be a life that many dream of, not working but having money to spend, but that’s not my kind of life.”

When Ekapob and his girlfriend fled the accommodations a few months later, Huot tried to convince him to come back.

“Call me when you are available. Don’t forget. There’s an urgent issue,” Huot told Ekapob in Thai, in a voice recording heard by Prachatai and VOD.

Ekapob said he refused to return to Huot or reveal his location. While hiding out outside Phnom Penh in late 2014, he and his girlfriend were granted asylum in New Zealand, where they live today with their three children.

“Khliang Huot was angry that he could not intervene in the [asylum process] to have my application dismissed,” Ekapob said. “He tried to tell me: ‘Don’t go anywhere. Just stay with me. Let me know whatever is not fulfilled. How much money you want, just tell me.’ At that time, I didn’t want money. I wanted a future.”

According to Human Rights Watch’s Sunai Phasuk, Huot would have been well-positioned to know whether any Thai exiles in Phnom Penh had done anything to violate the terms of their stay in Cambodia.

“The stay of those Thai exiles and whatever they do, that’s been on his watch,” Sunai said. “For better or for worse, what happens to the Thais there, he should know. And nothing so serious as a broad-daylight abduction should happen, and then the perpetrators could get away with it.”

In an interview, Huot, who was made a Phnom Penh deputy governor in July, denied having a close relationship with Wanchalearm, saying: “I know a lot of Thai people, over a hundred of them.”

He said he had met Wanchalearm when the activist came to Cambodia after the 2014 coup in Thailand. He declined to comment on Wanchalearm’s disappearance, saying he is “not involved in law enforcement matters” and only learned of the case from the news.

Nonetheless, Huot admitted police questioned him after Wanchalearm disappeared. He also expressed doubts over whether Wanchalearm was abducted altogether, saying: “No one would do it in an open space like that.” Whatever happened to Wanchalearm, Huot said, “don’t assume it’s related to politics. It might be a personal matter as well.”

Huot also denied playing any role in supporting Thai exiles. “I don’t have the ability to help them. I don’t have the budget to rent a place for them,” he said.

Contrary to Huot’s claim, a retired man living in the same Phnom Penh neighborhood where Ekapob had stayed said he had met several Thai exiles in the area after the 2014 coup, and that these exiles lived in a four-storey building known to be owned by Huot. The retired man said men working for Huot visited the property every month.

Huot’s relationships with Wanchalearm and other Thai exiles are not the only ones he sought to downplay.

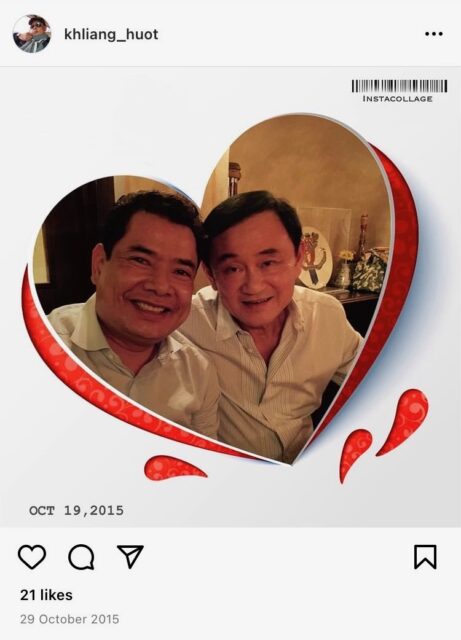

The official’s social media accounts show multiple photos of him with former Thai premier Thaksin Shinawatra, the leader of the Red Shirt movement who, like his sister Yingluck, was ousted in a military coup. (Thaksin was ousted in 2006.) Many of the Thai dissidents who fled to Cambodia after the 2014 coup, including Wanchalearm, were supporters of the Red Shirt movement and affiliated with Yingluck’s Pheu Thai Party.

Huot acknowledged meeting Thaksin on at least two occasions but says he doesn’t know the former prime minister personally. He said he once met Thaksin “unintentionally” in Hong Kong while shopping with his family and asked to take a photo with him, like he would with any world leader or celebrity.

“I am the king of taking photos when I travel,” Huot said.

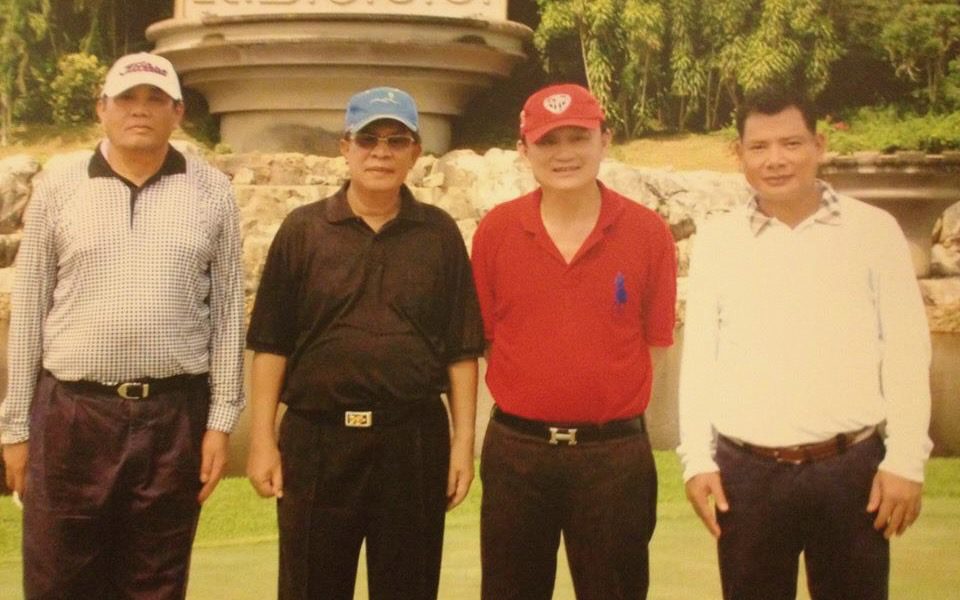

Photos posted to Huot’s Instagram account in 2015 show multiple photos of the pair, including one with the two men and their families. A photo posted to Huot’s Facebook account in 2012 shows a group of men including Huot, Thaksin and Hun Sen at what appears to be the Royal Brunei Golf and Country Club.

“What’s the problem with that photo?” Huot asked during an interview. About two hours after the interview, the photo was no longer publicly visible on Huot’s Facebook page.

More than a dozen other photos posted to Huot’s Facebook account in 2012 show him with various Thai political figures, including Red Shirt leaders, former MPs and ministers from the cabinet of Yingluck Shinawatra.

“I am someone who likes to drink. A person who likes to drink has a lot of friends. You shouldn’t wonder about that,” Huot said. “Cambodian people can make friends with foreigners, except in regards to political matters. I met with the Red Shirt people because I like wearing red too.”

Along with the photo showing Huot and Wanchalearm together, Sitanun included the caption: “It’s not over yet. We will start playing new games soon.”

She declined to elaborate.

Pheu Thai Operative

On June 21, Sitanun posted another photo to Facebook that drew attention to another aspect of Wanchalearm’s life that has been obscured since his disappearance. The photo shows the activist sitting in a train beside Yingluck Shinawatra.

Although Wanchalearm was best known in the years before his disappearance as an online political satirist and a critic of the Thai military junta, four sources say he was also deeply embedded in the Red Shirt movement and the Shinawatras’ Pheu Thai Party.

According to Sitanun, Wanchalearm worked for the current Bangkok governor, Chadchart Sittipunt, when he was minister of transport under Yingluck, from 2012 to 2014. Wanchalearm is also known within Pheu Thai circles to have helped stage the viral photo of Chadchart walking barefoot in his gym clothes, which was first published online in late 2013 and began to circulate again during Chadchart’s gubernatorial campaign this year. (Chadchart did not respond to a request for comment as of publication.)

Ben, Wanchalearm’s friend who suggested burning his belongings the day after he disappeared as a security precaution, said the activist was brought in to advise a Pheu Thai candidate on gender diversity policy in 2013, and was part of a team that supported Chadchart’s proposed infrastructure megaproject, which was found unlawful by Thailand’s Constitutional Court in 2014.

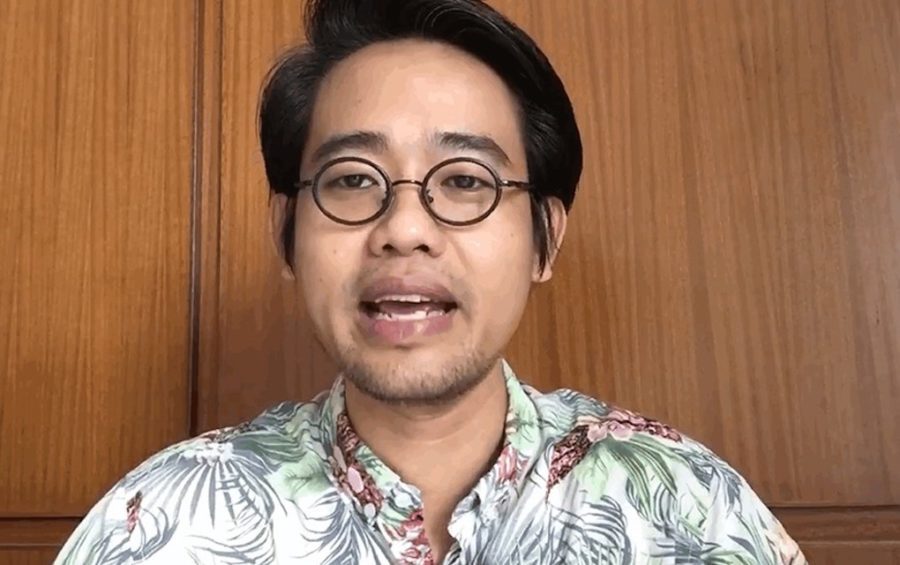

Nuttigar Woratunyawit, a Thai dissident who fled the country after being charged with sedition and royal defamation over a satirical Facebook page, said Wanchalearm was part of an initiative to create an online network of Red Shirt activists and Pheu Thai supporters to counter the People’s Democratic Reform Committee, which was established by right-wing royalists in 2013 to depose the Yingluck government.

More than two years after Wanchalearm’s abduction, however, the Pheu Thai Party, which controls more than a fifth of the seats in Thailand’s parliament, has made no visible effort to investigate or call attention to Wanchalearm’s disappearance, according to Human Rights Watch’s Sunai Phasuk.

“I knew he was involved with the inner circle of the Pheu Thai Party, and that’s why he knew a lot of the power players in the Shinawatra network,” Sunai said.

But no one seems willing to talk about this aspect of Wanchalearm’s work history, including Pheu Thai itself, despite the closeness between him and the party, Sunai said.

“I haven’t seen any commitment from Pheu Thai leadership to assist in the investigation,” he said.

Pheu Thai spokesperson Theerarat Samretwanit said in early July that no one in the party had information about Wanchalearm’s role in the party.

Sunai further suggests that Wanchalearm’s possession of a Cambodian passport shows “he must be very high up in whatever network that Pheu Thai had in Cambodia to get that kind of special treatment”.

“Not every exile Red Shirt got a Cambodian passport and a Cambodian name and could travel in and out of Cambodia freely, which Wanchalearm did. He traveled freely. So what role did he play? And who facilitated the arrangement for his Cambodian passport?” the researcher said.

The best-known example of a Thai exile holding a Cambodian passport is Yingluck herself, who is alleged to have used one to flee to Cambodia in 2017.

Sitanun said she has encountered friends of Wanchalearm who thought the Pheu Thai Party had been supporting her efforts to seek answers about her brother’s disappearance.

“That made me very angry because I’ve never gotten anything, and I don’t want anyone to claim that they were helping me,” she said. “They have never even said they were sorry, so how could they help me?”

“A Crazy, Ordinary Man”

From the day his neighbors agreed to remove his belongings until the present, people whom Wanchalearm had lived, worked and socialized with have gone on to obscure their relationships with him, concealing information that could contribute to the search for his whereabouts.

With little new information emerging over the last two years, Wanchalearm’s family has received no significant updates from authorities in Thailand or Cambodia, according to a lawyer representing his sister. In July, Cambodian Interior Ministry spokesperson Khieu Sopheak said “there are no new leads” in the case and that local law enforcement had “already lost the trail.”

Sopheak also claimed that previously published photos of Wanchalearm at Mekong Gardens were “faked,” and authorities did not find rental documents confirming Wanchalearm’s residence at the building where he disappeared.

In Thailand, Rangsiman Rome, spokesperson for the opposition Move Forward Party, said his party’s attempts through parliamentary mechanisms to inquire into Wanchalearm’s fate, such as summoning police to testify before a parliamentary committee, have yielded no results.

“The response from the government is very disappointing, and we don’t see any enthusiasm or progress,” he said.

Thus, the burden of keeping Wanchalearm’s plight in the public consciousness falls to Sitanun, who is facing charges for allegedly violating a public gathering ban under Thailand’s State of Emergency by speaking at protests about her brother’s disappearance. She has also been added to a police watchlist used to monitor activists.

“I’m frustrated as well because the government is ignoring this and doesn’t want to do anything, and it shows that you know about it, that you are involved from the beginning,” she said.

Others who have spoken out about Wanchalearm’s disappearance have also been prosecuted. Thai student activists Parit Chiwarak and Jutatip Sirikhan, who staged a protest in Bangkok the day after Wanchalearm disappeared, were sentenced in July to two months in prison and fined 10,000 baht (about $280) each for violating Covid-19 restrictions.

Amnesty International Thailand staffer Phattaranit Yaodam, Cross Cultural Foundation director Pornpen Khongkachonkiet and other activists were fined in August 2021 for obstructing traffic and violating the Public Cleanliness Act by speaking about Wanchalearm’s case during a panel discussion about enforced disappearance the previous month.

Sam, who lived in the Mekong Gardens building, said he wants the public to continue speaking out about Wanchalearm.

“If he died, I wish he was reborn in a good place. We’ve fought for him, wanting him to win. We didn’t abandon him,” Sam said, with tears in his eyes.

Nuttigar, who knew Wanchalearm from his days working for the Pheu Thai Party, and who remained in contact with him after he fled to Cambodia, also hopes people will not forget him or his fate.

“Don’t forget who he was,” she said. “He was just a crazy, ordinary man that was seen as a threat by the state until they had to get rid of him — so don’t let there be a second, third or fourth Wanchalearm.”

*Note: Pseudonyms have been given to individuals who expressed fears of reprisals.

Reporting by Yiamyut Sutthichaya, Matt Surrusco, Anna Lawattanatrakul and Jacob Goldberg

The authors reported this story with a Cambodian journalist who requested their name not be included due to fears of reprisal.

This story was updated at 9:11 p.m. on August 18 to correct the date on a photo caption involving Huot and Thaksin.