KAMPONG THOM — On one side of Kampong Thom province, the government has ended a community forest program, and remaining trees are being removed to create a World Bank project village. On the other side, farmers had land taken away — and their protests quelled with force — to make way for an earlier version of the project.

Both projects are part of the World Bank’s vision to give land and opportunities to Cambodia’s rural poor, but instead have left former residents wondering why they lost their farms or community forest.

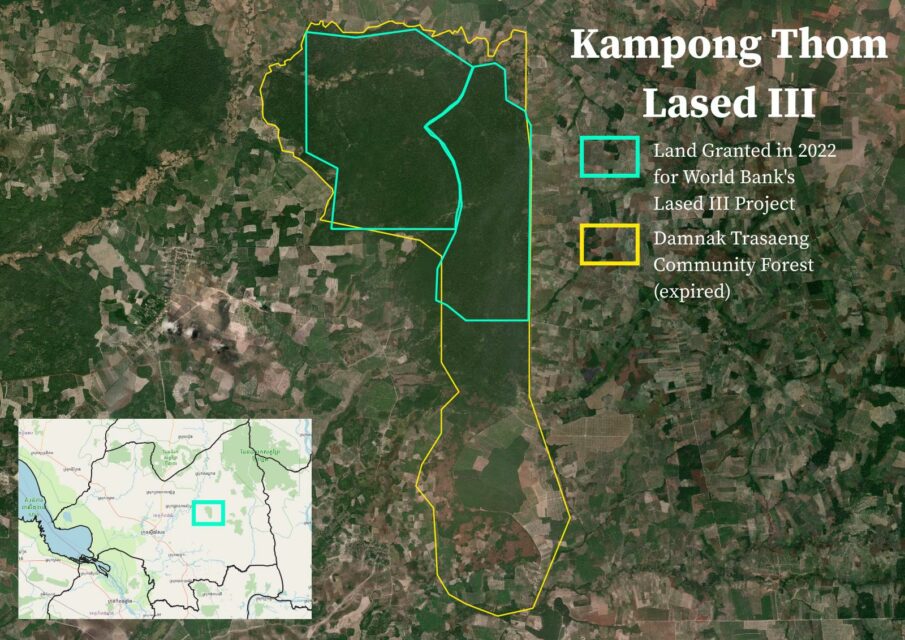

Reporters visited two land redistribution sites funded by the World Bank in Kampong Thom province, including houses already granted in Prasat Balaing district’s Doung commune and a plot of forest that’s about to be parceled out in Prasat Sambor district’s Sroeung commune. The communities say they lost land and forest in the process, while recipients said the additional land was welcome, but has not notably increased their incomes.

The World Bank created its Land Allocation for Social and Economic Development project, or Lased, in 2007. The project aims to help poor or landless people receive land in order to “escape poverty and participate in the development of their villages and communes.”

The bank led the government to create 13 new villages across the country until 2011, when the World Bank froze new loans to Cambodia for five years in response to authorities’ violent evictions at Phnom Penh’s Boeng Kak lake and its associations with problems in an earlier World Bank land-titling program.

Though the bank’s loan freeze lasted until 2016, project documents show that the World Bank began priming a new plot of land in Kampong Thom’s Doung commune in 2014 for the next phase of its Lased project.

Years before it was distributed in 2019, there were signs this land was already occupied.

Maryam Salim, country director for the World Bank, did not answer a question via email as to whether she knew of any former occupants on the Doung commune land distributed in 2019, or if she knew of a community forest in the new territory.

Instead, she said that the Lased II project had distributed 17,000 hectares to 5,091 families by its end in December 2022, with 3,960 families receiving land titles, adding that the selection process “includes a screening for environmental and social impact” and is “transparent and participatory and includes calls for applications, public display of applicant lists, the screening of applications, and public displays of selection lists.”

“Access to land and improving agricultural productivity is crucially important for Cambodians, particularly the rural poor,” she said.

Doung Commune Conflict

Around four years ago, Thiv Euth said he heard of other Doung commune residents selling their neighboring plots of farmland to a company, whose name he doesn’t remember. He held out on the offer and kept his 8 hectares.

“That land was from my father, and the reason I didn’t agree to sell it to the company is I wanted to share it with my kids,” Uth said.

The government then came for his land, and when he and other residents protested the loss of their farmland, the province sent armed military police to disperse them.

“We stopped talking about it because we’re scared of getting arrested,” he said of the conflict now. He said at least one protester went to jail.

Shortly after, he and other protesters were invited to apply for pieces of residential land and farmland in the same space he used to occupy.

“Those people protested and they had no choice in the end so they just applied for their land back,” he said. “I decided to apply too but it was just too late [to receive a plot].”

The Phnom Penh Post reported in June 2019 that residents of Doung commune sustained more than a month of protests, under the guard of nearly 100 armed police, after more than 470 families had been prevented from entering their land. The conflict site was only named as a social land concession, not specifically a Lased project, but two months later the newspaper reported that the government presented Doung commune residents with 2-hectare farm plots and a homestead under the World Bank’s Lased II project.

A summary of the conflict from the human rights organization Licadho says 586 families claimed land within the land concession, and that at least one organizer of the protests went to jail for six months.

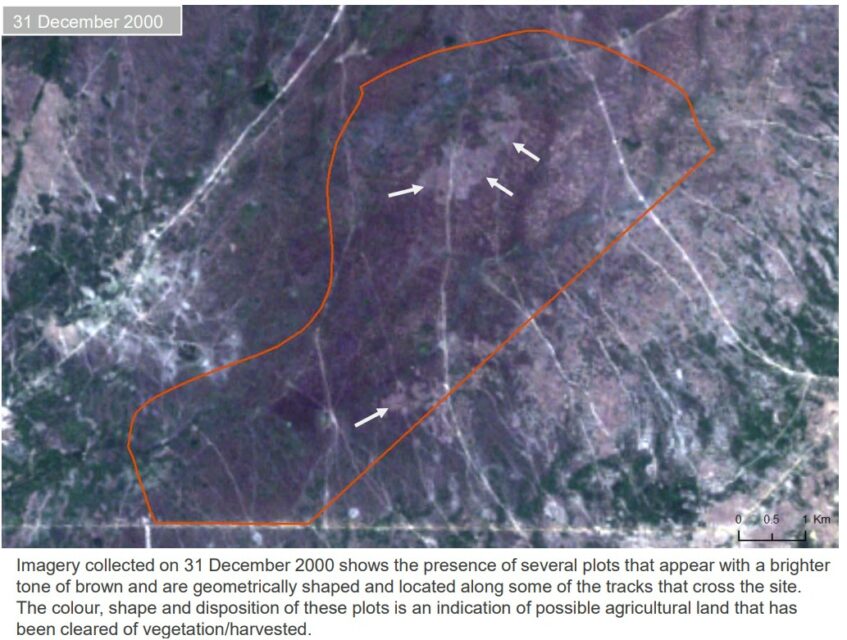

Even before the evictions happened, there was evidence that people were occupying the land for generations: The U.N.’s Satellite Center published a report on the Doung commune land concession in 2017 showing clear evidence of farmland consistently cultivated within the area through the 2010s. The U.N. report revealed farms in the area in 2000 — aligning with Euth’s claim that his father farmed that same land before him.

Since losing the land, Euth, 65, said he struggles to earn enough to support his 12 children, though he has a small plot elsewhere.

“I only depend on the rice field, and now I just have a small piece of land and I have to survive from it,” he said.

Logging of Community Forest

Residents around Sroeung commune’s Phum Thmey heard this year from district authorities that their 200-person village would receive new neighbors, said Lao Theary, a 40-year-old who runs a small drink shop on the west side of the village.

Though they’re close to two contiguous Lased concessions in Prasat Sambor and Sandan districts, which were granted in January, she said she had already heard that Phum Thmey residents wouldn’t benefit.

Theary said she didn’t mind, but Phum Thmey village chief Pa Sok was not thrilled about the prospect of new neighbors.

Sok said Phum Thmey and two other Sroeung commune villages used to receive money for a community forest area that overlaps completely with the two new Lased sites. The funding stopped coming at one point, but Sok said Phum Thmey still made an effort to protect the area designated for their village.

“That is state land, but we want to protect the forest, so we gathered the community to protect the forest,” he said.

The forest used to have wild pigs, deer, wild chickens and turtles, but since the new village was announced, about 50% of the trees — especially big and valuable trees — have been logged, he said.

“Since Lased came they started cutting down the trees,” he said. The village chief said it was people from other districts who had come to take pieces of the forest.

Sok said he wanted to ask officials to preserve about 150 hectares, which he said had religious significance to residents. He also expressed disappointment that his village was not even included in the Lased plans.

“After they took the land we were discouraged. People felt a sense of loss about it,” he said. “At the end the benefits went to other communes.”

The Damnak Trasaeng community forest only received funding for patrols from 2016-2018, but the volunteer patrols continued long after the payments stopped, said Houng Ouun, a member of the forest patrol.

The community forest used to stretch almost 4,000 hectares, according to a map of community forests compiled by the environmental NGO Recoftc. Ouun said the community forest members were now trying to register the remaining 200 or 300 hectares of forest as a protected area again, but protecting the area was a challenge because of loggers descending on the Lased area, she said.

“We stopped [patrols] when Lased came,” she said. “They took the forest. We have no hope to work anymore. We stopped. We’re tired.”

Lased Part-Timers

When reporters visited Doung commune in late November, recipients of the Lased land said they were living on their new plots about half the time.

A half dozen farmers who spoke to reporters said they already had another patch of land elsewhere in the commune before the World Bank project came in and gave them second plots.

Salim, the country director for the World Bank, said the families should have been screened for “any existing land ownership” in addition to their financial need.

But the discrepancy could be a lack of official recognition for the existing plots: Residents said they didn’t have land titles for their earlier plots in Doung commune.

Tiem Khan, 42, and Chong Thon, 46, a couple that owns a corner shop, were setting up a station to raise mole crickets, which when fried make a crunchy snack. Lased allowed the family to move out of their parents’ house, but Thon said she was able to sell more drinks and snacks when she lived at her parents’ place.

The new land comes with challenges for the family: Khan said the land is dry, so he struggles to get water, but Thon said that earlier this year the water was up to her knees, and the family had to pitch a tent on the street, which was at a higher elevation.

“It won’t be a good rice [harvest] this year because of the floods,” she said.

Doung commune chief Peung Sohorn, one of only three chiefs elected nationwide from the opposition Candlelight Party, said the Lased land was a new opportunity for residents to develop their agricultural businesses.

“They help with [residents’] multiple needs. It helps the baby try to walk again,” he said.

Resident Dith Mun does not yet have a land title for her Lased plot. She heard she had to occupy her land for five years to earn a land title, and began bringing her herd of buffalo to her new land. She laughed when asked how her farming is going, saying she makes little money when she farms a small plot of rice.

The 56-year-old farmer said she was happy with her new plot, but she doesn’t feel confident she can keep it. Her other, older land also has no title, but at least the family had been there “from my ancestors,” she said.

“I’m worried because I want the land title. It’s a new place here, and I’m hesitant to say if I’ll be able to stay here forever,” she said.

Additional reporting by Danielle Keeton-Olsen.