PU TONG VILLAGE, Mondulkiri — Dusk leaves an orange tinge on treetops and tin roofs as Pon Peul herds five buffaloes from a grazing field back to her wooden stilt house in northeast Cambodia.

She pours water from a 20-liter jerry can into a bowl for the buffaloes to drink as darkness falls over Pu Tong village. Shards of solar-powered light poke through cracks in the walls of homes.

Peul, 23, a member of the Bunong indigenous community, speaks softly to her 3-year-old son as she clears away uneaten hay left by the buffaloes underneath their home.

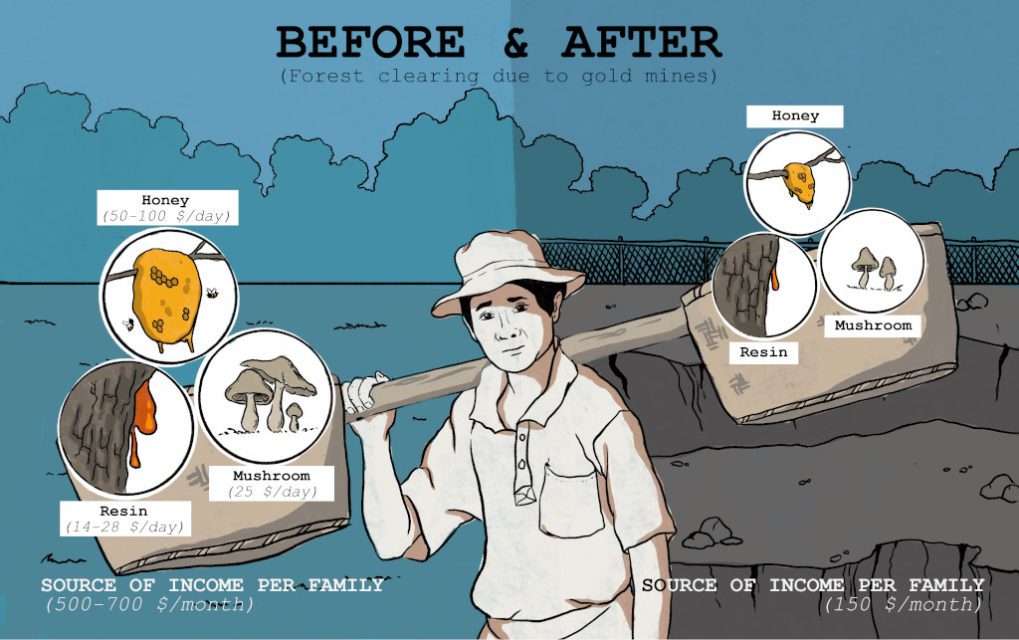

A nearby vegetable field yields long beans, ground nuts and tapioca that the family sells at a local market. But it’s far short of what they earned from the tree resin, honey and mushrooms collected in the forest before the development of the Okvau Gold Project, Cambodia’s biggest gold mine.

“The forest is valuable to us because it provided for the family,” Peul told VOD during a recent visit to her village 15 km from the mine site.

“We regret losing our trees around the mine, but we cannot do anything about it,” she added.

Pu Tong, in Keo Seima district’s Chung Phlas commune, is the nearest village to the project site in the northeast province of Mondulkiri, about 275 km from Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh.

The Okvau project — which poured its first gold in June last year — is operated by gold miner Renaissance Minerals, a wholly-owned Cambodian subsidiary of Australian-listed Emerald Resources.

Prime Minister Hun Sen, in a Facebook post in June, called the project a “great achievement” for Cambodia’s economy and its post-pandemic recovery.

He said the project — carved from the protected Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary in Keo Seima district — would operate with a “high responsibility for the protection of the environment and society.”

The company said in response to questions emailed by VOD that its environmental and social initiatives aim to prevent or mitigate the negative impacts on local communities and “set the benchmark for an environmentally and socially responsible, sustainable and transparent mining industry in Cambodia.”

VOD also sent questions to several government ministries but did not receive replies to its queries.

Nevertheless, some Bunong feel left behind as their cultural traditions and livelihoods — such as collecting food and non-timber products from nearby forests — are lost or restricted by economic development that they say benefits others more.

Their experiences underscore the challenges facing indigenous communities as they seek to protect a traditional way of life at a time when Cambodia’s government is issuing more mineral exploration licenses to tap the country’s resource wealth.

“Everything changed,” said Bunong lawyer Samin Ngach, who is all too familiar with the struggles of his community in Mondulkiri. “People tried to adapt to a new environment, but it’s something very dangerous to lose culture, lifestyle and traditional practices.”

“What the Bunong people have lost since the mining operation is the traditional practices — rotational farming practice and collection of non-timber forest produce. When the forest is cut down, they lose honey, rattan and resin,” he said.

Land of Gold

Cambodia’s resource-rich northeast has a long history of artisanal gold mining that in recent years has drawn international exploration and mining companies seeking to develop potentially lucrative deposits. In Okvau itself, there were around 140 individuals operating in July 2016, an impact assessment for the company found, though it added that the figure was made up of transient communities that have reduced in size over the years.

Renaissance Minerals became a serious player in Cambodia’s mining sector in 2012 when it acquired the local unit of OZ Minerals for about $30 million. The deal included the Okvau and adjacent O’Chhung exploration licenses which covered some 400 sq km in Mondulkiri.

Four years later Renaissance merged with Australian-listed Emerald Resources to develop the Okvau project. The project is forecast to produce 107,000 ounces (about 3,000 kg) annually over the seven-year life of the single open-pit mine.

Renaissance, which holds a 15-year mining license with the option of two 10-year renewals, discovered in 2019 a high-grade feeder zone to Okvau with stronger ore assaying per ton.

The potential deposits and Cambodia’s favorable investment policies underpinned the company’s bid to secure financing to develop the mine. Canadian investor Eric Sprott agreed in 2019 to provide a $60 million debt facility, as well as access to a $100 million acquisition and development facility to fund “future development and acquisition opportunities.”

“The important thing is that investors must be convinced the project is viable and de-risked. It would appear so far this is the case with Emerald,” Trevor Turnbull, director at Toronto-based Gold and Precious Minerals Equity Research, said.

Sprott is viewed as a “very sophisticated investor” with a track record of investing in junior mining ventures, he said.

“If he invested in Emerald he must be comfortable with the project’s potential profit margins and the management team’s ability to deliver on their plans,” Turnbull added.

Since mining began last June, the Okvau project has yielded over 2 tons of semi-pure gold doré alloy valued at about $111 million based on prices at the end of last year.

For Cambodia, the project is forecast to generate $40 million in total revenues and taxes from annual gold revenues of around $185 million. Given this income potential, the government has ramped up investment approvals. Last November, seven companies were issued licenses to explore in five provinces, including Mondulkiri.

The Okvau project lies within the Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary, a forested area covering 2,225 sq km that is among the largest biodiversity sanctuaries in Southeast Asia. The area also carries great social, cultural and economic importance for the Bunong, who rely on non-timber forest products for food, construction, energy and medicine. However, the area is under increasing pressure to be cleared for agriculture or economic land concessions.

During community consultations for the Okvau project’s Environmental and Social Impact Assessment, residents raised key concerns about the loss of forest, their lands and traditional ways of life. One question cited in the ESIA report focused on whether the mine’s location near a community protected forest will “result in the loss of resin trees in the protected forest, which are used by indigenous people.”

Among the more valuable non-timber forest products, resin tapped from dipterocarp trees is used to make varnish, epoxy and soaps, and is a major source of income for Bunong families.

Approved by the Environment Ministry in 2017, the ESIA, conducted by two Australian and Cambodian firms, included public consultations with potentially affected residents and local authorities in Mondulkiri and neighboring Kratie province. The assessment covered segments including the project footprint, development area, Okvau settlement — around 140 persons who lived within the site prior to formal operations of the mine — and the impacts on communities depending on Prek Te River upstream and downstream.

‘Life Has Changed a Lot’

Before he passed away in 2018, Pon Peul’s father would spend three to four days a month in the forest collecting hard resin. On a good day, he brought home 50 kg of hard resin fetching 500 riel ($0.13) per kg, or about $6 a day.

On other days he tapped trees for liquid resin. “Each time he would bring back three 30-liter buckets of resin, which could be sold for 40,000 riel ($10) to 50,000 riel ($12.5) per bucket,” she said.

Today, Peul says their income from resin trees has dropped sharply because trees were cut down to prepare for the mine. When they can afford fuel, Pon Peul’s brother will travel once a week by motorcycle into the forest to tap resin trees. A trip earns the family $25-50 to buy food and other essentials.

“These days, we can only collect 10 kg of solid resin a day. Most of the trees are gone,” she said of her brother’s trips.

The ESIA report said construction of the mine would require the removal of 467 hectares of dipterocarp, evergreen, mixed deciduous and semi-evergreen forest. Although the dipterocarp resin trees covered the smallest affected area (17 hectares), their loss has been felt by Bunong families.

Srav Krahorm, a former soldier and now chief of Pu Tong village, where the Bunong comprise 50 of the 424 resident families, said his village was grateful for the road improvements and a new water well provided by the mining company as part of its environmental and social programs.

Seven Bunong families in the village also received compensation for 140 resin trees located within 10 km of the project site that were removed during construction.

“The company paid about $40 per resin tree,” he said. The payments did not include resin trees in state forest areas that were cleared during construction.

“There is still some forest to find resin and honey, but it’s not as active as before and they had to change to do other work such as farming or working for others,” said Krahorm.

The company has implemented a tree planting program as part of its environmental and social initiatives in the project area. Some 2,350 beng trees — which are illegally logged for their flame-colored wood in the province for furniture making — were planted by the end of 2020. However, there appears to be no similar program for dipterocarp resin trees.

Ploek Phearum, facilitator of an informal network of indigenous communities in Mondulkiri, said the company had paid $50 per tree in compensation to affected people in neighboring Memang commune. That was not enough to offset the loss of income from resin, honey and mushrooms collected in the forest.

“In the past, when they went to the forest they could collect enough food to store for 3-4 days, but now they cannot find food for even one day,” Phearum said.

She estimated a typical Bunong family now earns about $150 a month from traditional activities in the forest, far less than what she said was $500-700 a month before the mining project.

“Life has changed a lot. We don’t go to the forest as often,” Phearum said, adding that most families try to eke out a living from growing vegetables and rice and tapping the remaining resin trees.

Though unaware that the company was planting beng trees, she questioned why they were not resin trees, which would be more “useful for us.”

“If they plant other trees, it is useless. The villagers or the next generation cannot benefit from it in the future. Resin trees are resistant to the weather,” Phearum said.

She is worried that in 20 to 30 years, after the company has taken all the gold and left, the fate of the ethnic people is doomed.

“What benefit is there? So, I think the villagers should get resin trees back after the company leaves. I think the company should plant resin trees [which is] better than other trees,” she said.

‘Positive Legacy’

In an emailed reply to questions from VOD, Emerald Resources said it recognized that mining has an “unavoidable impact on the environment” and has put policies and programs in place to minimize the impacts and mitigate long-term legacy issues.

Emerald noted its “commitment to respecting the rights of all stakeholders,” to “prevent or mitigate any negative impacts of its activities,” and to “maximise its positive impacts” and ensure that “their operations do not contribute to conflict.”

“Emerald recognises and respects the cultural values, traditions and beliefs of the communities where it operates, including those of ethnic minority [highlanders] and indigenous peoples,” the company said in the email, which also highlighted its environmental and social activities.

As the Covid-19 pandemic eases, the company said it aims to expand its activities in affected communities and planned to update the public at an open day in late May.

“The company will look to the community to identify inclusive, long-term sustainable initiatives that will support affected communities during and before operations,” the company said.

One potential issue is land rights. As Cambodia seeks more foreign investment in mining, tensions over land titles for indigenous communities could rise, observers say.

Land Rights

Cambodia has a history of disputes over land rights, many dating back to the 1970s when the Khmer Rouge regime destroyed property records, and all housing and land became state property.

More recently, as increased foreign investment led to more concessions of public lands to private companies, disputes arose over deforestation and land grabs around concession areas that often involve lands claimed by indigenous communities.

Cambodia voted for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People in 2007, but has not ratified a convention empowering indigenous people to give or deny free, prior and informed consent for actions that impact their lands or rights. As a result, free, prior and informed consent is not commonly observed in Cambodia.

In 2009, indigenous land rights were enshrined in Cambodia’s Land Law, but the process to secure individual or communal land titles is a long, complex exercise that can take years to complete.

Data compiled by the NGO Forum showed that currently only 33 of the country’s 455 indigenous communities have received communal land titles, or shared rights over a specific piece of land.

The Land Ministry has indicated another six or seven communal land titles could be issued this year, NGO Forum said.

Ploek Phearum, the Mondulkiri indigenous community facilitator, said indigenous people often hold a less secure “soft title” issued by local authorities, but that does not prevent authorities from earmarking these lands for economic concessions. Some indigenous villagers will end up selling their soft titles for very little in return, she said.

“Tycoons, government officials or businessmen come to buy land along streams from the Bunong people to turn it into plantations,” he said. The price for a soft title can range from an 80 kg bag of rice, 1 or 2 liters of alcohol, or $200 cash.

“They sell the land to survive and end up buying food when they used to be able to live off the forest,” said Phearum.

Cambodia announced last year that it would review the land title process, although there have been few details on the review.

While that process plays out, one mining exploration firm is trying to create a template for collaboration between the industry and indigenous communities.

Canada-based Angkor Resources announced in May what it called a “groundbreaking” mineral development agreement with the Jarai ethnic community living near the Andong Meas exploration site in Rattanankiri province.

The pact included “technical assistance and education, capacity building, surveying and mapping, and border identification for communities to pursue a communal title on their traditional lands” and Angkor cited progress in a November update.

Asked if Emerald would offer similar assistance to indigenous communities around Okvau, operations manager Bernie Cleary said the company was not aware of “any desire from local leaders or community members to assist with land titling” in the Chung Phlas and Memang communes.

He said officers from the Land Management Ministry regularly visit the two communes, the last visit being six months ago, to conduct land inspections and issue titles to legally-settled families.

Pu Tong village chief Srav Krahorm said the community planned to seek a communal land title, but did not provide more details.

A Better Life?

Indigenous lawyer Samin pointed out that efforts to safeguard traditional customs and land rights are hampered by the fact that many indigenous people have little access to education in remote areas, might not understand the Khmer language or be familiar with their legal rights.

“When they talk about environmental issues or [gather views] for the ESIA, what is the percentage of people who understand those terms?” he said, noting that companies and local authorities typically focus on the benefits and less on potential negative impacts.

“They will say ‘When we do this, we will help the community get a better life. You will have a road, school, job and income, and make your family better. Are you happy? If you are happy, raise your hand.’”

“They will raise their hand and the company staff will take a picture. The company would claim in the report that ‘yes, people agree, they are happy’. They [the company] would also say, ‘don’t worry, we guarantee everything,’” Samin related.

“When nature is lost, lives are affected and the governance system is also affected because indigenous people believe in the forest, mountain, river and stones. It is their right, which the government and companies must respect,” he said.

Meanwhile in Pu Tong, some families have retreated into their homes while others sit outside and chat under a starry night.

There is no breeze, only mosquitoes on a balmy night. Trees would be good to cool down the atmosphere, the villagers agree, but they are gone now.

Some fear their culture and customs will also fade away.