It was a picture-perfect moment.

The late King Norodom Sihanouk, yet to be reinstated to the throne at the time, and Prime Minister Hun Sen, standing in a motorcade on the streets of Phnom Penh, their hands clasped, arms raised in triumph before a cheering crowd, the joy on their faces frozen in time and film.

It was November 14, 1991. Sihanouk had just returned after nearly 13 years spent in exile after the collapse of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979. He’d been away for a long time, but on that day, just three weeks after he joined other Cambodian factional representatives to sign the landmark Paris Peace Agreements, he was home — and what’s more, embracing his chief political rival for all to see.

The scene is now set to be printed on a commemorative 30,000 riel banknote released by the Cambodian government to mark the 30th anniversary of the adoption of the Paris Peace Agreements on October 23, 1991. Though its legacy has been hotly debated since, the treaties included in the agreements are seen by most as setting Cambodia on track to end its long-running military conflict. Among its stipulations, the deal created an avenue for the return of refugees, emphasized protections for human rights, called for a ceasefire between the country’s four main armed factions, and invited the massive presence of the U.N. Transitional Authority of Cambodia in part to create conditions to hold a national election.

Though their execution would be lacking, the sum total of the agreements created a period of detente that spun the country onto its modern political trajectory.

The symbolism of the image that will grace the 30,000-riel note is a simple one of reconciliation. But the road to that moment was long, more than a decade in the making and intertwined with tectonic shifts in the geopolitical arrangements that helped usher in and sustain the Khmer Rouge in the first place.

“The signing of the PPA occurred thanks to the weakening of the Soviet bloc,” said Prince Sisowath Thomico, an outspoken nephew of the late king, looking back at the process ahead of the 30th anniversary. “That left the West and China free to negotiate the content itself of the PPA.”

Thomico, who spent much of his life in France, was a personal assistant to Sihanouk in the post-Khmer Rouge years as the charismatic statesman planned his long return from exile. Though Thomico wasn’t directly involved in the negotiations of the peace agreements, he was party to the years of intra-factional dialogue that preceded them. In his later political career as a member of the now-banned opposition CNRP, Thomico would argue the Cambodian government had abandoned its obligations under the agreements signed in Paris.

Long before that, he was a booster of his uncle, whose royalist Funcinpec party was one of the four main groups jockeying for power in a new Cambodia. At that point, while the U.N. and other outside powers tested the wind for a brokered treaty, the exiled factions were making their own calculus of conditions back home.

“[Sihanouk] had the idea that the ‘Cambodian problem’ was a Cambodian problem — every Cambodian faction had to meet and discuss to try to find a negotiated solution, a peaceful solution,” Thomico said.

About four years before riding with Hun Sen in the streets of Phnom Penh, Sihanouk would meet his rival in 1987 in a village outside Paris. The reportedly six-hour conversation was arranged by Pung Chhiv Kek, a medical doctor who went on to found the rights group Licadho.

Sihanouk came as the representative of a tripartite government-in-exile formed in 1982 as a coalition of three of the four Cambodian factions that would later sign the peace agreements. These included the Khmer Rouge, Sihanouk’s royalist Funcinpec and the nationalist KPNLF founded by the anti-communist Son Sann, who served as the tripartite’s prime minister. Sihanouk, who was first crowned as king in 1941 but abdicated in 1955 to become prime minister, was considered a prince at the time.

As far as the international community was concerned, the tripartite governed from exile as the legitimate representatives of Cambodia. The fourth and final faction to later engage in the Paris Peace Agreements resided back within the national borders, where Hun Sen had consolidated a government in Phnom Penh with backing from Vietnam — which occupied Cambodia for 10 years after helping to topple the Khmer Rouge — and its Soviet patrons.

Before about 1985, Thomico said, negotiations between the tripartite and the Phnom Penh government didn’t bear much fruit.

“The situation within the government was not stable enough for a dialogue to take place, and so we had to wait until 1987 before Hun Sen was able to go to France and meet with Prince Sihanouk,” he recalled. “After that, things went smoothly and very fast, after that first meeting.”

But as the factions maneuvered among themselves, larger powers had been shifting in the background. After a failed attempt at a 1981 conference to address what some referred to as the “Cambodia problem,” U.N. secretary-general Pérez de Cuéllar tapped career diplomat Rafeeuddin Ahmed, known to friends as Raffee, to go to Southeast Asia as part of renewed efforts to broker a peace.

A transcribed interview with Ahmed conducted in 2013 as part of a U.N. oral history of the long negotiation process captures some of the Cold War maneuvering that for years stalled a comprehensive pact.

“The international conference had failed the previous year, because of the boycott by Vietnam and the Soviet Union,” Ahmed recalled, explaining that the allied duo had pressed for a limited, regional conference to make peace in Cambodia. Secretary-general de Cuéllar, “looking to see whether we could get the UN in the act,” was an advocate of the international approach. That was a strategy also backed by Asean and, softly, China.

Ahmed continued his tour of the region to promote an international conference on Cambodia that would include regional countries, including China, plus the U.N. Security Council states and some others, such as India. This plan seemed to be gaining momentum until the Phnom Penh government, Vietnam and Laos came out publicly against the expanded forum.

“That was the kiss of death, as soon as that came out then the ASEANs said ‘No,’ they objected to both forms,” Ahmed remembered. “That was a rather bitter disappointment, because if they had only let us know quietly, then we could have worked it out and the Paris conference which took place, you know, ten years later, may have taken place earlier.”

Still, that was hardly the end of the U.N.’s organizing role. In 1985, de Cuéllar was visiting Phnom Penh in his official capacity to demonstrate that his office was taking the peace process seriously. By 1989, two years after Hun Sen had met Sihanouk in Paris, the political recession of the USSR had left its client Vietnam to seek an exit from its 10-year occupation of Cambodia.

As the window for change opened wider, international negotiators stepped up their own proposals for a widely brokered peace. In early 1990, Australian diplomats under then-Foreign Affairs Minister Gareth Evans compiled a plan that came to be known as the “Red Book.” They would present that plan at a conference in Jakarta that brought together the four Cambodian factions plus Vietnam, Laos and the Asean countries as they were then: Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam would join later in the decade.

“After the [Jakarta meeting] in early 1990 the detailed negotiations were basically taken over by the [Security Council permanent members] and UN, with Indonesia closely engaged as co-chair, and Australia stepping back into the background – although we still talked to the key players, and the Red Book remained the central blueprint throughout,” Evans wrote in an email to VOD.

By the time the Jakarta conference was through, he added, the structure of the Paris Peace Agreements had largely been hammered out.

“The Ministerial session in Paris in 1991 was like the last stage of the Tour de France — purely ceremonial speeches and signing,” Evans recalled.

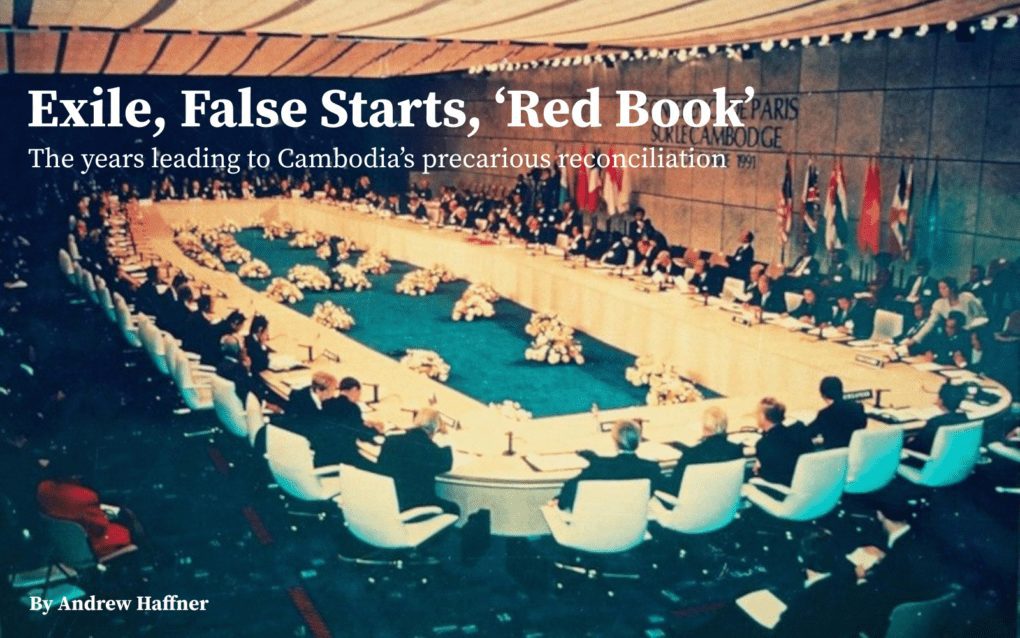

Photos of the meeting itself, held October 23, 1991, in the Kleber International Center in the French capital, depict men in suits, signing documents, applauding, shaking hands. Three weeks later, Prince Sihanouk returned to boisterous crowds in Phnom Penh before riding in the motorcade with Hun Sen.

About four-and-a-half months after that, the UNTAC mandate rolled into Cambodia with the weight of 16,000 military personnel, 3,600 civilian police and 2,000 civilian staff. The unprecedented U.N. intervention ran from March 15, 1992, to September 26, 1993.

By the time UNTAC left Cambodia, its overseers had expended more than $1.6 billion on a host of programs intended to fulfill the peace agreements, an ambitious docket that included democratizing the country while disarming its warring factions, including the mistrustful Khmer Rouge.

The director of all this was director Yasushi Akashi, who had sweeping authority over what existed of the Cambodian state. As head of UNTAC, Akashi could pass laws and remove Cambodian bureaucrats from their jobs. UNTAC officials even had a prison facility of their own built to house three Cambodians arrested on allegations of excessive political violence.

Throughout this time, humanitarian adviser Dennis McNamara oversaw UNTAC’s human rights component, a vital stipulation of the peace agreements. McNamara was interviewed in 1998 as part of the U.N. oral history project. Looking back on the five years since the mandate ended, he spoke frankly about UNTAC’S failures and successes.

“I think it was probably the most intrusive mandate then entrusted to a peacekeeping operation, including in the human rights area,” he said of UNTAC’s mission as laid out in the Paris Peace Agreements. “We had a pretty wide mandate to take all necessary action to try and obtain this neutral political environment that was called for the elections; and to draft laws; and to promulgate laws, which we did; and to help draft the constitution, which we didn’t do very well.”

McNamara also counted the failed disarmament of the factions as a critical piece of the UNTAC legacy. As part of that, he told the interviewer in 1998 that none of the parties backing the mission “had any stomach for engaging the Khmer Rouge”, to the point where U.N. peacekeepers were the ones being forcibly disarmed by guerillas.

Though the inclusion of the Khmer Rouge in the peace agreements had been seen as a thorny but necessary measure, the tension during UNTAC would prove to be too much. The Khmer Rouge withdrew from the agreements during the process and resumed its insurgency.

Despite the breadth of its mission, UNTAC honed its focus on coaching Cambodia through a national election. McNamara said that process was marred by open acts of political violence — “mainly by Hun Sen and his forces against FUNCINPEC political party” — which took first priority in his human rights work. Other issues he addressed included discrimination and violence against Cambodia’s ethnic Vietnamese minority, as well as abuse within the criminal justice system.

By the time elections happened starting May 23, 1993, the Khmer Rouge had withdrawn, boycotting the polling itself. Funcinpec emerged with the largest vote-share, but their electoral win was quickly challenged by the Hun Sen government, which used the threat of armed force to win equal representation in the new government.

For McNamara, the trajectory of the first election was an outcome of the UNTAC mandate, which stressed polling above all else.

“The basic necessary safeguards parallel to an election were not in place,” he said. “Partly because of the time factor, but also because UNTAC and its leadership and the donors and the Secretary-General wanted to have an election and then get out. The message was very clear: Have the election and get out. Even some of the Paris Accord-mandated Responsibilities — drafting the constitution, for example, which we started on — we were told, ‘Leave it, it’s their business.’”

“We didn’t follow up on the various safeguards that should have been put in the laws to try and preserve this very vulnerable, nervous, fledgling elected parliament.”

For many observers, the outcome of the 1993 election set a tone for the contests that would follow in Cambodia, clearing the way for the ruling CPP to gradually assimilate or attack the former factions, chiefly Funcinpec in a series of violent clashes in 1997. After the adoption of the Cambodian Constitution on September 21, 1993, the role of the Paris Peace Agreements took an increasingly contested place in political society, with opposition groups insisting the agreements are still binding, especially in regards to democratic and human rights. The ruling party rejects that argument, and last year removed an official holiday commemorating the anniversary from the public calendar.

But the image of Sihanouk’s triumphant return and public embrace of Hun Sen remains in the public eye, if only on the new 30,000 riel note. For some who were party to the long journey to a peace deal in Paris, that might be the only real proof any reconciliation occurred.

Earlier this week, as he considered the past from a cafe in Phnom Penh, Prince Thomico said he believes the failure of the peace agreements to bring together the factions only dug deeper the country’s political dysfunction.

“A lot of mistakes have been made. The situation in Cambodia now comes from the consequences of those mistakes,” he said.

Though he listed other failures of the agreements’ implementation, the prince believed a key rupture point was the withdrawal of the Khmer Rouge from cooperating in the peace process — despite being a signatory — and, later, refusal to participate in the 1993 election. At least for the prince, that set a precedent of refusing civil means of resolving disputes, preserving the role of armed resistance in Cambodian politics.

“The PPA was empty without the reconciliation. If you have one party which would not agree with this reconciliation, then everything had to be redone and rediscussed,” he said. “The main roots of the PPA was reconciliation, and if you don’t have that, then the door was open to whatever happened.”