Nav Srey Pov did not ask herself at first what she wanted to be when she grew up. As the seventh child in her family, she quit school before graduating high school like the rest of her siblings and got a job at a garment factory in Dangkao district.

But she quickly found the thrum of the factory lines suppressed her, she told VOD.

“I felt that I wanted freedom,” she said. “I wanted to see the outside world.”

She found that freedom in boxing, she said — at first, while watching matches, and later with her father’s encouragement, she entered the ring in 2015.

“People have asked me why I did not go to work at the factory and [instead] turned into a boxer, which causes pain all over the body. I just kept their words [in my mind] and say to myself, ‘One day when I am famous, they will stop saying that.’”

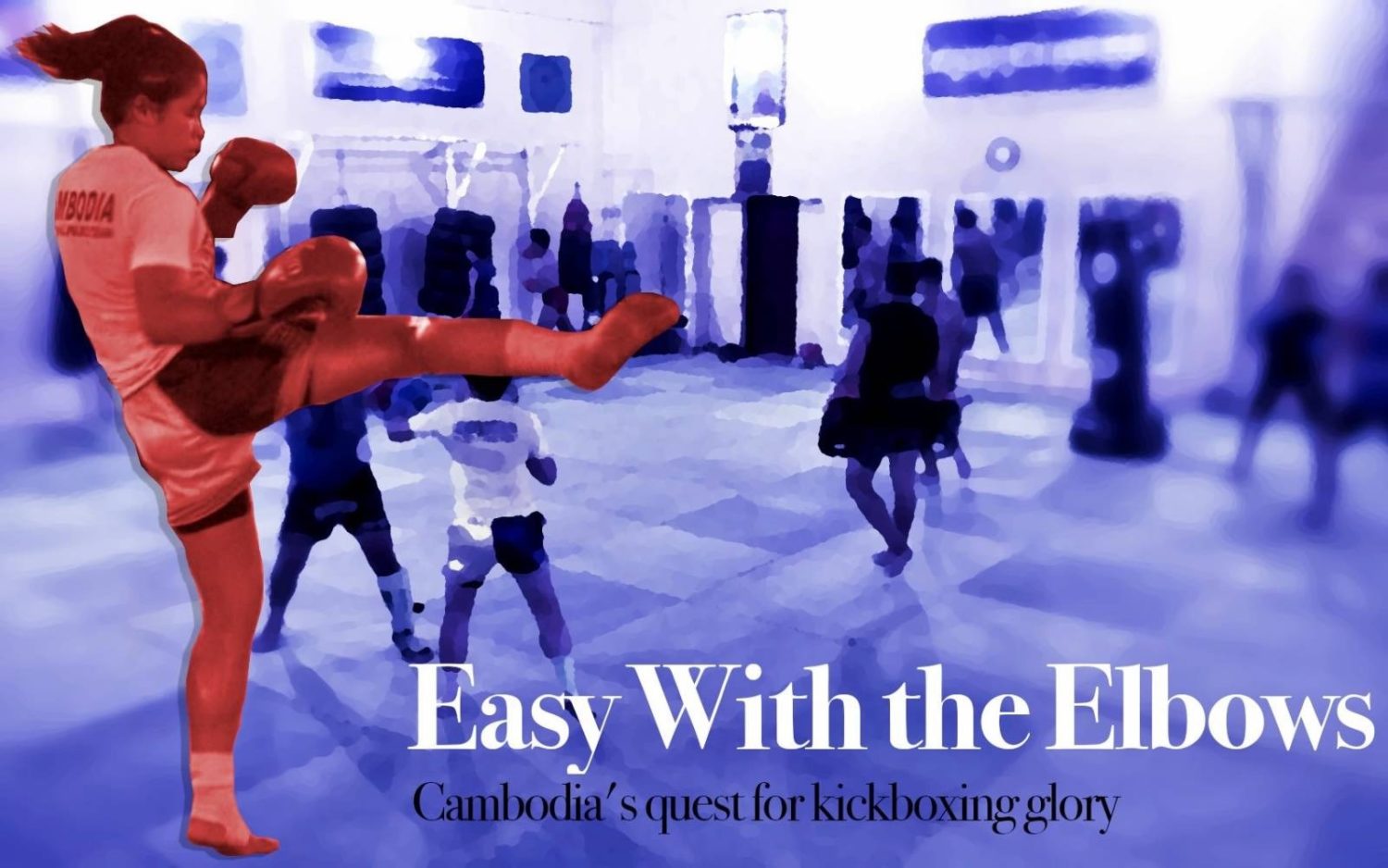

Seven years after she started training kun khmer boxing, Srey Pov, now 27, has gained a reputation as one of Cambodia’s best fighters, and she aims to represent her country when Cambodia hosts the Southeast Asia Games next year. With less than a year to go, she and other kickboxers are preparing for a fight with all spotlights on them.

Stepping into the Ring

Kickboxing was one of Cambodia’s best sports in the 31st SEA Games in Hanoi, with one Cambodian fighter, Toch Rachhan, taking gold in men’s 57kg weight class.

All but two of Cambodia’s nine gold medals this year were earned in different combat sports, with three Cambodian athletes taking gold in vovinam and one gold medalist each in kickboxing, wrestling, taekwondo and muay thai.

When Cambodia hosts the games next May, the pressure will be on kickboxers and kun khmer fighters, said San Sao Yann, head coach for Cambodia’s competitive kickboxers.

“The public and people focus on us as the trainers,” he said. “People trusted us so if we don’t do well, these millions of people in Cambodia will blame us.”

Both Sao Yann and his athletes are originally trained in kun khmer — the more modern form of Cambodia’s martial arts, in addition to ancient, expansive combat sport and ritual l’bokator.

The coach has to train his athletes to adapt their strategy to compete in different sports, because kun khmer utilizes elbows and knees, which are not used in kickboxing. However, the way that athletes place their kicks and punches on opponents can be different across the sport, so the fighters are learning what their weaknesses in kickboxing are and trying to fix them.

“They already know kun khmer. We just trained them using hands and legs,” for punching and kicking, respectively, he said.

Heng Sokhorn, president of the Kickboxing Federation, said that his federation, as well as some 40 other sports federations preparing for the games, are making sure that their athletes are prepared for the games, as well as for hosting athletes from the region.

The kickboxing federation is currently training 15 athletes in the combat sport, with one main fighter and one reserve athlete ranging in weight classes from 45 kg to 81 kg.

“Both athletes and leaders are very busy in preparation as the hosts of the SEA Games,” he said. “Within 64 years already, we have not hosted the games, so we have to be careful with the quality of the athletes.”

Cambodia’s coach Sao Yann said he was worried that his athletes might struggle under pressure to succeed in their home country, but he has high hopes they will outscore their rankings in Vietnam this year.

“Returning from [this year’s] SEA Games, they already know the important points of competition,” he said. “They know what their weak points are… they understand and have tried hard by themselves, and we’re just strengthening [them] more and now, they’ve made a lot of changes.”

Cambodia’s Top Sparrers

Kickboxer Toch Rachhan now has a reputation to uphold after the SEA Games in Vietnam, where he took home the first of Cambodia’s nine gold medals.

But Rachhan’s legacy is deeper than the games: The 26-year-old said he picked up kun khmer at 13, inspired by his grandfather and two uncles who studied the martial art, trained and competed.

“It’s my dream from childhood, I thought of nothing beside boxing,” he said. “I want to become a famous boxer. I saw my uncle become famous, [so] I wanted to be a famous boxer and earn more money.”

Rachhan said he dropped out of school around 15 or 16 years old to train full time, but his conviction occasionally wavered. He said he almost quit several times after whiffing in some fights, saying he didn’t think he had the ability to win.

But Rachhan ratcheted up his training in 2019, after he was encouraged by his uncles as well as his own passion for the sport. In addition to the SEA Games gold, Rachhan said he hasn’t lost in 10 professional fights in a row.

In between rounds of sparring at the old Royal Cambodian Armed Forces stadium in Toul Sangke I commune, Rachhan said he felt success comes “only if you have the will and want to be famous. … If you just love it, you will not be able to do it.”

His victory in Vietnam has not made him pompous, as Rachhan said he is training harder to protect his streak.

“We will be a host and we went to the SEA Games in Vietnam and we got success, but if we don’t train hard and if we fail in our territory, we will be ashamed,” he said.

Srey Pov, the 27-year-old kickboxer, said she has already proven to her family that she can earn a living out of the sport. Her career in kun khmer and kickboxing can cover more of her family’s expenses than factory work, where she earned around $80 or $90 per month.

“At first, I did not think much about boxing [as a career], I just tried to work at a factory to pay off debts for treating my father’s illness, but when I started boxing, it helped my family a lot,” she said. “Even if it’s painful and tiring, we get money immediately and we are happy.”

She met with a reporter between rounds of shadow boxing and kicking the bags at the military stadium, working on adding strength to her hits.

Srey Pov has started fighting in competitions abroad, and won a bronze medal in the 2019 SEA Games in the Philippines.In 2018, she was named Top Female Fighter by the Yangon-based World Lethwei Championship, a competition for the Burmese martial art.

But she felt disappointed in her performance in Hanoi this year, where she lost in her first bout, or a set of 3-minute rounds in a fight, of the 51-kg weight class competition.

Srey Pov said she was preparing instead to fight in the 48-kg weight class, saying other players’ height gave them advantage over the 1.55-m fighter.

Even though that loss almost brought her to quitting after the 31st SEA Games, Srey Pov said she has her family’s support, and she’s determined to try again in her home country.

“I challenged my mother that I will make it. I will make it. I will not make my family lose face.”

Other Fighting Events in the SEA Games 2023