SIHANOUKVILLE — At 11 p.m. on September 17, Feng Kai* finished showering and went to bed as usual in Kaibo, Chinatown — but then he was asked to get up again and go into the office. There, he was told the scam operation he had worked at for about six months was moving to another location near National Road 4.

This was the start of The Big Transfer. No one had expected it just days before, according to foreign workers.

Some of Sihanoukville’s largest scam compounds had already been operating for more than three years, they said. But those criminal operations — where authorities have since acknowledged that workers were bought and sold, tortured and locked up — finally became a police priority. And just before the police raids arrived, releasing thousands of people from the compounds, thousands of others appear to have been moved out to other locations.

Feng’s scam operation pretended to offer part-time jobs that required victims to download an app and put credit on it, and also had a fake investment angle, he explained. It was based in the Kaibo area near O’Tres beach, and there were 8,000-10,000 people there working in several scam operations before the transfers started, he said. Police have said they found 2,000-3,000 foreign workers in Sihanoukville compounds when they arrived.

On the night of September 17, all of Feng’s colleagues walked downstairs to find the lot filled with buses, pickup trucks and Toyota Alphard vans, though he could not say exactly how many.

Feng and his colleagues got into one of the cars. It was raining at the time, and the convoy left Chinatown in the rain, he recalled. At the front of the convoy was a Mercedes Maybach sports car with flashing hazard lights, and there were other Mercedes-Benz luxury cars in the convoy.

The convoy eventually came to a compound next to National Road 4. (Feng asked that this compound not be named to avoid identifying him, as he is still in Cambodia waiting to return to China.)

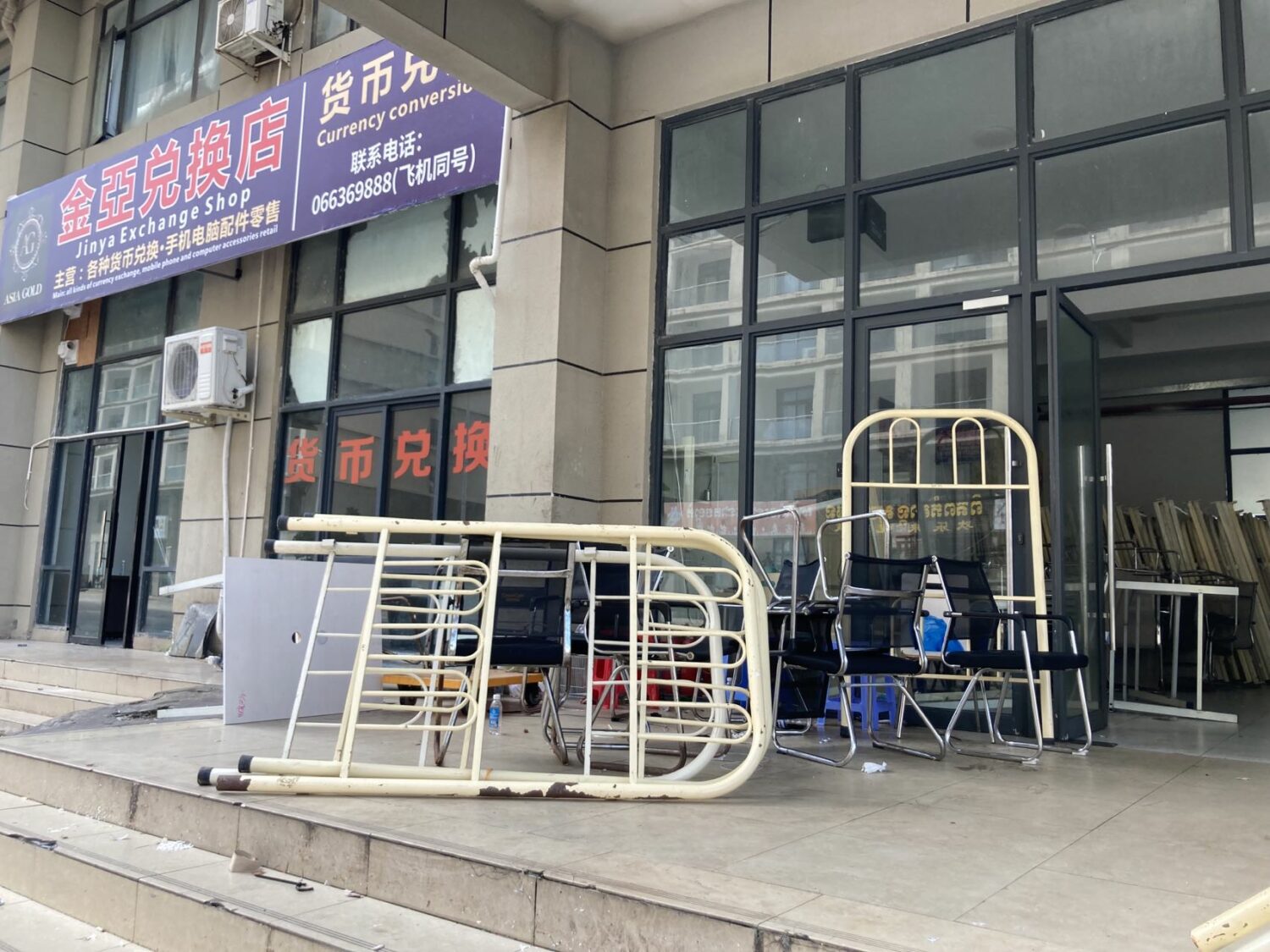

Due to the extremely hurried transfer, many of the dormitories in this compound had nothing but empty bed frames. Feng lay on a metal bed without even a mattress, and pulled a coat over his body under heavy air conditioning. “I didn’t sleep all night. It was too cold,” he said.

The next day, the workers were moved again, this time to a large hotel in downtown Sihanoukville, around 20-stories tall.

Feng and his colleagues were transferred to the hotel by bus. “In that bus there were two teams of about 50 people, the bus was so full that some of us stood in the middle without a seat,” he said.

Feng said his superiors had told the workers many times that the boss of Chinatown was very powerful. The police would not check Chinatown before checking other places, they had told the workers. But this time they didn’t know what had happened and why the police came to Chinatown. After the transfer, syndicate bosses destroyed all mobile phones, computers and hard disks, Feng said.

There was disorder as workers were moved around, and Feng found an opportunity to escape the hotel and is now trying to get home.

What transpired in September was The Big Transfer — but it was supposed to be The Big Crackdown.

After many months of impunity for scam compounds, Cambodia was feeling the heat internationally: Media outlets around the region had begun picking up on the enslavement of their citizens in Cambodia, a U.N. envoy warned of the situation, and the U.S. downgraded the country in its human-trafficking ratings. Interior Minister Sar Kheng opened up his Facebook page to receive human trafficking complaints, and was flooded with hundreds of pleas for rescue. Police began their raids, but many syndicates had already slipped away.

On the evening of September 22, VOD reporters saw a yellow bus drive into an alley near the closed Great Wall, or Chang Cheng, compound. Dozens of people got off the bus and entered a five-story apartment. It was not clear how many people were inside.

In other areas, compounds that had long been locked down with armed guards, barbed wire and closed gates were seemingly opened up. But on September 22, when a VOD reporter went to Jinbei 4, he was blocked by a security guard despite the open gates. This falsely-open situation also happened at the K99 compound, which opened its gates on September 19, but a security guard still sat at a table by the entrance, and reporters were stopped from entering.

Another forced scam laborer, Liu Hua*, is still working in a compound in Sihanoukville. He has requested help but has been shuffled around, including being moved again just two weeks ago.

Liu told VOD that he did not believe the massive industry had been shut down. “There are thousands of scam companies in Cambodia, hundreds of thousands more people are trapped in these companies, trafficked and forced to scam,” he alleged. “Most companies are still doing it, their business goes on, it does not have a big impact on them.”

Some criminal scam operations were accustomed to moving around to avoid police — one former scam worker said his operation had moved every three months to different compounds. A Chinese police officer stationed in Cambodia also told VOD of many scam operations having begun moving from compound to compound every three months or so.

The transfer of scam companies did not just happen in Sihanoukville. Li Ping* was in a compound named Dong Tai in Svay Rieng’s Bavet city in September. At that time, inside two 11-story buildings were more than 100 Chinese and around 300 Vietnamese workers, he said.

Li was transferred with his colleagues on September 20 on two buses, leaving Bavet and moving into a four-story villa, sharing GPS coordinates of a building that appears to be in Borey Phnom Penh Thmey’s The Harmony Ville.

According to Li, the villa belongs to his boss, and at that time around 30 people had moved to that villa. His Chinese boss previously had a supermarket in Phnom Penh, and after making some money, he opened a scam company in Bavet, Li said.

On September 23, Li got an opportunity to run away from the villa with a friend. But others were unable to get out and were moved back to Bavet on October 5, he said.

*Names of human trafficking victims have been changed for their safety.