Prime Minister Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit has left the cleared area of Phnom Tamao forest after occupying it for about a month starting in August, seeming to transform a piece of the protected forest into an apparent park after a land giveaway controversy embroiled the area just three months ago.

On a visit to the former forest on Wednesday, reporters found the cleared area fenced off but its entrance accessible, marked with a sign noting the “Phnom Tamao Arboretum” is open all day. A half-dozen visitors sat on motorbikes and a truck carried water throughout the clearance.

In what was previously a zone of short but dense deciduous forest, meter-high saplings were evenly planted in rows across the expanse of sand, with weeds and some sheets of grass in between. A new man-made lake and bridge sits in the middle of the park, with large but newly-planted tree trunks supported by scaffolding flanking a water feature.

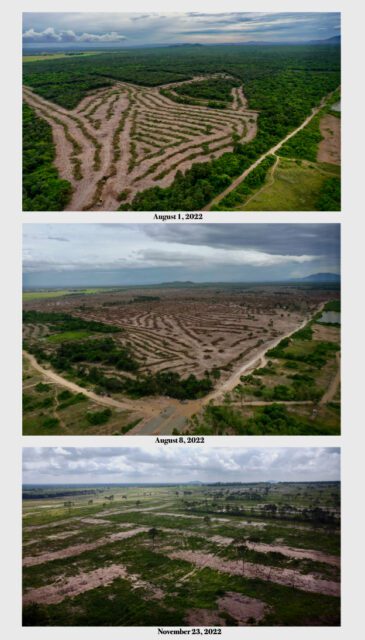

Phnom Tamao forest lost more than 500 hectares from its northwest corner, as the Cambodian government quietly granted hundreds of hectares to tycoons Khun Sea and Leng Navatra starting in May.

Hun Sen, who originally signed off the forest for satellite city plans, called off the razing in early August after mass disapproval from Phnom Penh residents who had grown up frequenting the protected forest. Another tycoon, Mong Reththy, hosted a highly-publicized replanting campaign for about one week before the prime minister’s personal bodyguard unit occupied the forest.

But now the area is quiet. Flies swarmed reporters when they arrived: One pagoda resident said they were compelled into the park by the Khmer Fresh Milk farm to the east, while a guard said compost had been recently spread around the coconut farm to the north, owned by the family of deceased deputy prime minister Sok An.

When asked about the coming plans for Phnom Tamao forest, Takeo provincial spokesperson Meas Uy referred to the Agriculture Ministry. Ministry spokesperson Im Rachana said nothing has changed since August, when the government revoked the land concessions.

“The ministry has announced. There is no more than that,” Rachana said. “If there is any plan or development in the area, the ministry will announce it.”

The bodyguard unit left the forest about two months ago, said Neang Nou, 33, an assistant at a pagoda. He told reporters they shot down two drones documenting the area during the occupation.

Wat Thmor Antorng’s chief monk Sot Phally said the bodyguards didn’t occupy the pagoda land itself but visited the monks while they occupied the area. No one — bodyguard or tycoon — came to apologize for the loss of the forest, he said.

“They came and felt sorry for the damage around the pagoda, because they didn’t expect the clearing would be near the pagoda,” he said.

Wildlife Alliance director Nick Marx said his organization — which runs the animal rehabilitation center and zoo within the forest — was not involved in the replanting. Marx, who previously pleaded in Khmer to stop the concessions, said Wildlife Alliance donated some hardwood trees to the project, which he believed would be developed into an arboretum and botanical garden.

Sandy roads snake around the razed Phnom Tamao forest. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen)

Sandy roads snake around the razed Phnom Tamao forest. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen) Large swaths of the razed Phnom Tamao forest remain deforested. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen/VOD)

Large swaths of the razed Phnom Tamao forest remain deforested. (Danielle Keeton-Olsen/VOD)

Keo Somrith now camps outside the southern entrance to the cleared area, near Phally’s pagoda. Usually a zookeeper, Somrith said he is paid by the state to guard the clearance, adding he gets a little extra money for conducting night patrols.

Since the area became open to the public, people come every night to see it: “People are surprised to see that it’s beautiful [still]. At first I also felt sad.”

The area was under tight control when the bodyguard unit was there. Now he sees animals trying to eat the plants and residents picking edible plants in the area. His primary concern is the animals, he said, directing his dogs to chase out pigs.

“[The animals] have been destroying the plants, so we built the fence, otherwise they will destroy it,” he said.

Wild pigs used to come to Wat Thmor Antorng every evening, and sometimes in the early morning, to eat scraps left at the pagoda, but now there are fewer visiting animals, said Nou, the pagoda assistant.

But Phally noticed the razings brought more people. His pagoda is northeast of another pagoda that’s directly next to the Phnom Tamao Zoological Park, and the latter inevitably receives more foot traffic than his own. “I felt excited but not happy [to see people returning, as] I felt sorry for the lost forests,” Phally said.

Phally recalled that when a tycoon came to bless the land for its development, a monk that they brought in for the ceremony said that the spirits sent a warning: If you clear all this land, your family will be separated. The forest has a “powerful force,” he said.

“This place can’t be taken away,” he said. “There are around 5,000 spirits. The strong spirits sent warnings [about dangers] to their home.”

Nou was not confident that humans would listen to the spirits’ cautions.

“They spent a lot of money on this plan” for the satellite city, he said. “I’m scared they might take it back in the end.”