Cham Sor first took out a $4,000 microfinance loan in Siem Reap about a decade ago, using it to build her family home with high ceilings and a storefront.

But the small plot of land she put up as collateral in Kokchak district’s Veal village — and where she has lived since 2005 — is considered state-owned public land under the Apsara Authority, which oversees Angkor Wat less than 3 km away. Now the government is forcing roughly 10,000 families around the park to destroy their homes and leave, claiming that the evictions are necessary for the park to maintain its Unesco world heritage status.

That prospect didn’t seem to concern her lender, Sathapana Bank: Sor said she renewed the loan again five years later, both times showing representatives her soft land title.

“When we first got here, we used an oil lamp and the house was made from leaves until we got the loan and built this big house,” said Sor, 62. “I haven’t finished my payments to the bank, but they already want to kick me out.”

Interviews with people within Angkor Archaeological Park and relocation site Run Ta Ek indicate that microfinance institutions have been lending to people with Angkor land as collateral for years. Some borrowers used the money to build or expand their homes, which the government has now said necessitates their eviction.

Angkor park borrowers — who mostly rely on selling food and souvenirs to tourists — said that the MFIs had not explained what may happen to their loans now that they are being kicked off the land they put up for collateral, but are worried about making monthly payments in a relocation site with few job opportunities.

Like Sor, many families have soft titles, which are recognized at the local but not national level.

“Almost every house” has a loan, said Seang Sokchea, a 32-year-old father living on a quiet road nearby and has a $5,000 loan with Acleda. Since the evictions began, “the microfinance institutions have been silent. They haven’t shown up here recently.”

Residents named Acleda, LOLC and Prasac among the institutions that have sent representatives door-to-door around Angkor Park neighborhoods, handing out information about loans of varying sizes. VOD spoke with four people whose loans ranged from $1,500 to $15,000 and said they had relatives and neighbors with loans up to $40,000.

People living in Angkor’s “yellow” zone — where people may volunteer to leave but are not prioritized for current evictions — said lenders were still visiting the community as recently as mid-January. Those in the “red” zone currently being evicted said lenders had stopped trying to sell new loans, but have not explained what could happen to their existing debts.

Construction at Run Ta Ek relocation site for Angkor Archaeological Park evictees pictured on January 17, 2023. (Fiona Kelliher/VOD)

Construction at Run Ta Ek relocation site for Angkor Archaeological Park evictees pictured on January 17, 2023. (Fiona Kelliher/VOD) A house in the relocation site Run Ta Ek on January 18, 2023. (Fiona Kelliher/VOD)

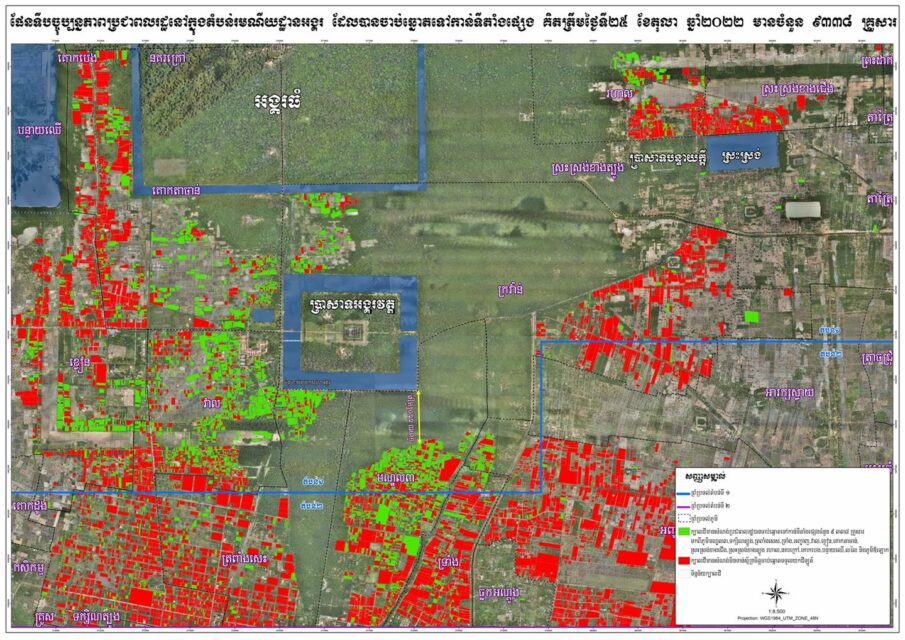

A house in the relocation site Run Ta Ek on January 18, 2023. (Fiona Kelliher/VOD) Angkor Archaeological Park residents who have accepted relocation (in green) as of October 26, 2022. (Chea Sophara’s Facebook page)

Angkor Archaeological Park residents who have accepted relocation (in green) as of October 26, 2022. (Chea Sophara’s Facebook page) A development plan for Siem Reap’s Run Ta Ek commune, a designated resettlement site for Angkor evictees, on October 8, 2022. (Hean Rangsey/VOD)

A development plan for Siem Reap’s Run Ta Ek commune, a designated resettlement site for Angkor evictees, on October 8, 2022. (Hean Rangsey/VOD)

Apsara authority spokesperson Long Kosal claimed not to know about the history of loans in the park. While people have historically been allowed to live on Apsara land and have business there, they cannot use the land to borrow from banks, he said.

“I want to clarify that you can’t take the state’s land as collateral,” he said. But “related to these cases, I don’t know.”

Those displaced from the Angkor park are meanwhile busy building homes, digging wells and using trees to string up electrical cables in the Run Ta Ek relocation site, where they have been promised hard titles on 20-by-30 meter relocation plots but have yet to receive them.

On a recent morning, evictee Soun Chanraksmey dug holes around her family’s new Run Ta Ek land, setting up a well system. Three years ago, she took out a $15,000 loan from Prasac by putting up two plots of Apsara land she occupied as collateral.

She used the money to build a second house elsewhere in the park near Angkor Thom, but she has stopped now that the evictions are underway. The majority of her former neighbors in Kokchak’s Khvien village are in the same situation, she said.

Chanraksmey’s repayments are $308 monthly. She has $12,400 left to repay.

“We owe them,” she said. “No matter what, we need to finish our payments. It’s easy for us to borrow, but we need to pay it back.”

Cambodia’s microfinance industry has faced rising scrutiny in the last few years as human rights groups and journalists have documented systemic abuses by microlenders, including the forced sale of borrowers’ homes or land. By the end of 2021, Cambodians held about $14.4 billion in microloans, according to human rights organization Licadho.

The U.N. has reported average repayments in Cambodia of about $182 monthly, with land being the most common form of collateral.

Naly Pilorge, Licadho’s outreach director, said that the organization has seen “all of the country’s largest MFIs accept soft land titles as collateral, as appears to be the case in this situation,” including titles that overlap with other claims such as indigenous communal land titles.

“The legal status of the land titles is often irrelevant for an MFI, because MFIs pressure borrowers to sell land outside the legal system,” she said. “What matters, in their cold and greed-driven calculation, is whether the collateral can be used to coerce the borrower into selling their land, or taking other extreme measures, such as child labour.

“This is why all land titles need to be returned to borrowers, to ensure these abuses will not take place,” she added.

Kaing Tongngy, head of communications at the Cambodia Microfinance Association that represents the industry, acknowledged that people living on state land in Angkor Archaeological Park have received microfinance loans, adding that reporters’ questions seemed to imply that microfinance institutions tend to take people’s collateral, but “it isn’t like that,” he said.

“Microfinance takes the collateral to keep it in people’s minds that they have the obligation to pay back their loan.”

A 2022 study funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development concluded that about 167,000 Cambodian families had been forced to sell land in the last five years because of debt.

Tongngy defended loans in the Angkor area on the grounds that bigger banks would not let people borrow money on Apsara land. Sathapana, LOLC, Acleda and Prasac did not respond to requests for comment.

“Microfinance takes a risk to provide loans for people, otherwise people won’t be able to build a business,” Tongngy said. “If microfinance and banks won’t provide loans for people, what will people do? First, people won’t have money for their business, and second, they might borrow from other people.”

As evictees settle into their new lives at Run Ta Ek, a fresh cycle of lending could soon start again. In September, Prime Minister Hun Sen called for microfinance institutions to provide low-interest loans to people moving to relocation sites.

Back in Angkor park, Cham Sor, the woman who took out two loans in the past decade for her house, said she didn’t want to take out yet another loan if she eventually is forced out of her home. After 10 years of repayments, she still owes $1,000 in interest to Sathapana Bank.

“If we go there, we won’t have any business,” Sor said. “How can we pay them back?”