A volunteer who’s taking calls for help from Chinese nationals working in Cambodia-based scam companies is hitting walls on all levels when trying to bring these cases in front of Cambodian police.

Reporters followed Lu Xiangri, a Chinese national who has taken over a hotline for foreign workers wanting to escape scam businesses in Cambodia, as he attempted to inform police of cases and help people get out of Sihanoukville companies.

Lu has been collecting accounts from people who say they are being detained or abused within foreign-operated online companies ever since Chen Baorong, a longtime businessman in Cambodia and leader of the China-Cambodia Charity Team, was arrested after speaking out about the alleged, then retracted, “blood slave” story.

On a trip to Sihanoukville in late May, Lu filed complaints seeking the rescue of 11 men allegedly detained and forced to work in seven compounds. He visited three commune police stations, the Sihanoukville city and provincial authorities, and sent messages to officials and a police hotline. None of the individuals were released, and people at two locations messaged Lu that they had faced consequences after Lu notified the police.

His method has been to raise the issue to the Chinese Embassy and Cambodian authorities, as well as post on the Facebook pages of Prime Minister Hun Sen and Preah Sihanouk governor Kuoch Chamroeun in order to catch their attention. However, Lu said that he was getting frustrated that authorities weren’t taking his claims seriously.

As reporters approached the Sihanoukville police station with Lu, he said in English: “The first time I come here, they want $3,000,” referring to the ransom that a scam company wanted in exchange for a previous rescue he attempted.

Collecting Cases

Lu, a 32-year-old Chinese national who co-owns a restaurant in Phnom Penh, was assisting the China-Cambodia Charity Team while it was helping Chinese nationals leave jobs throughout Cambodia where they were allegedly detained or tortured. When Chen was arrested, he inherited the SIM cards that people would contact to ask for assistance from the team, but Lu said he was no longer associated with the group.

After the organization stopped taking these cases, Lu began taking them to the police by himself, but he said the process has become harder, with police ignoring the cases.

Before Lu reported cases to authorities, he collected basic information from each person: passports, or Chinese ID cards if they did not have passports, the location where they’re stuck, and details about why they want to be rescued.

Lu shared several written narratives from victims with VOD, translated from Chinese and including names and passport photos. Identification is being withheld because the people are still detained by businesses in Sihanoukville.

Two people said they were kidnapped in Sihanoukville, while three others said they had responded to different job ads: for construction work, a restaurant gig and a Taobao shopping site customer-service job.

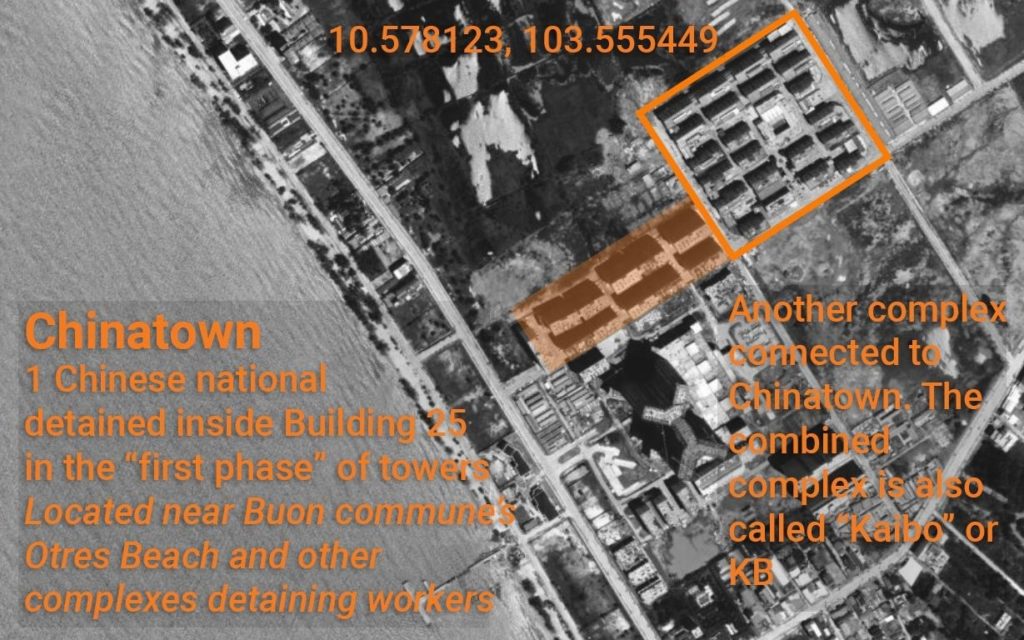

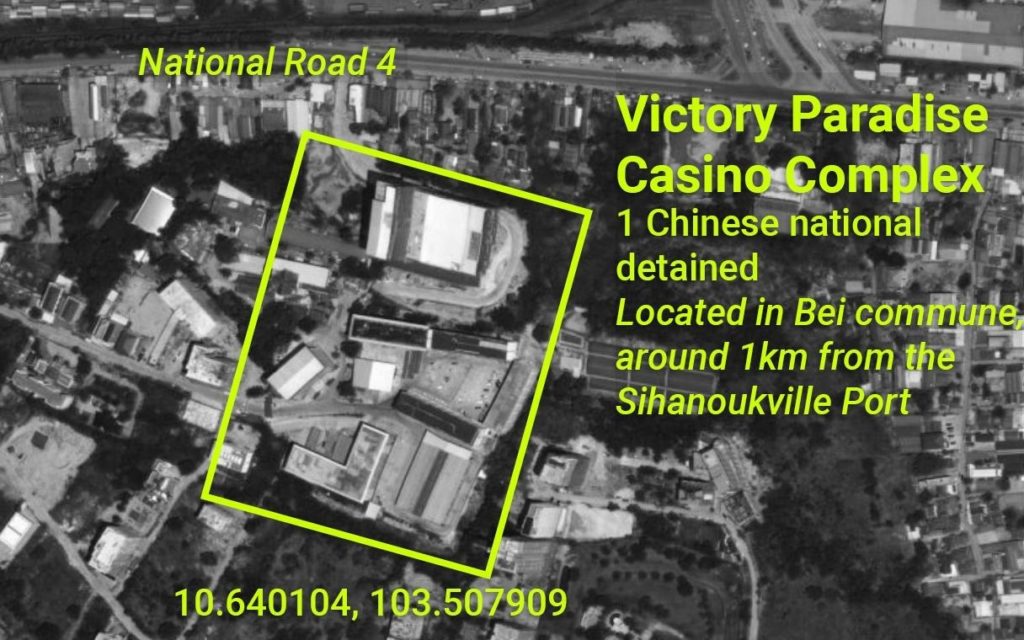

One 22-year-old man told Lu in a message that he had been sold multiple times before he ended up detained inside the Victory Paradise casino complex in Bei commune. He claimed he had been held in multiple buildings inside the Kaibo Chinatown compound in Sihanoukville’s Buon commune, as well as other parks.

While inside one of the Kaibo buildings, the man claimed he had attempted to request help from Preah Sihanouk governor Chamroeun’s Facebook page by sending a message, and he was given a contact for the Preah Sihanouk immigration police.

The man then claimed that immigration police had arrived at Kaibo, but rather than leading to his release, he was sold again.

“When [the provincial immigration police officer] arrived at the gate of Kaibo Park, he took my photo and told the park that he wanted to go in and save me. As a result, the park property directly notified the company and they threatened me to withdraw [the complaint to] police, otherwise I’ll be beaten and sold again,” he wrote in his request for help.

“My body can’t hold it anymore. I don’t dare to call the police for help,” he wrote.

The Process

Working together with a reporter to send messages in Khmer, Lu in late May sent passports and phone numbers of seven different locations to a hotline established by the National Police.

Lu then called a Chinese consular office in Sihanoukville, which told Lu that the families of the victims should be making the request. Lu recalled the conversation in Mandarin back to reporters, saying that he had told the consular officer that the victims should have already sent emails requesting help to the embassy in Phnom Penh.

Shortly after, Lu received a phone call purportedly from national police in China asking him how to rescue Chinese nationals in Cambodia.

“My gosh, so many police and reporters text me to save the people. I don’t know what to do,” Lu said in English.

Reporters then accompanied Lu to different police stations across Sihanoukville on May 31. At each location, a reporter helped translate information from Lu into Khmer, and reporters clearly announced their jobs at each location.

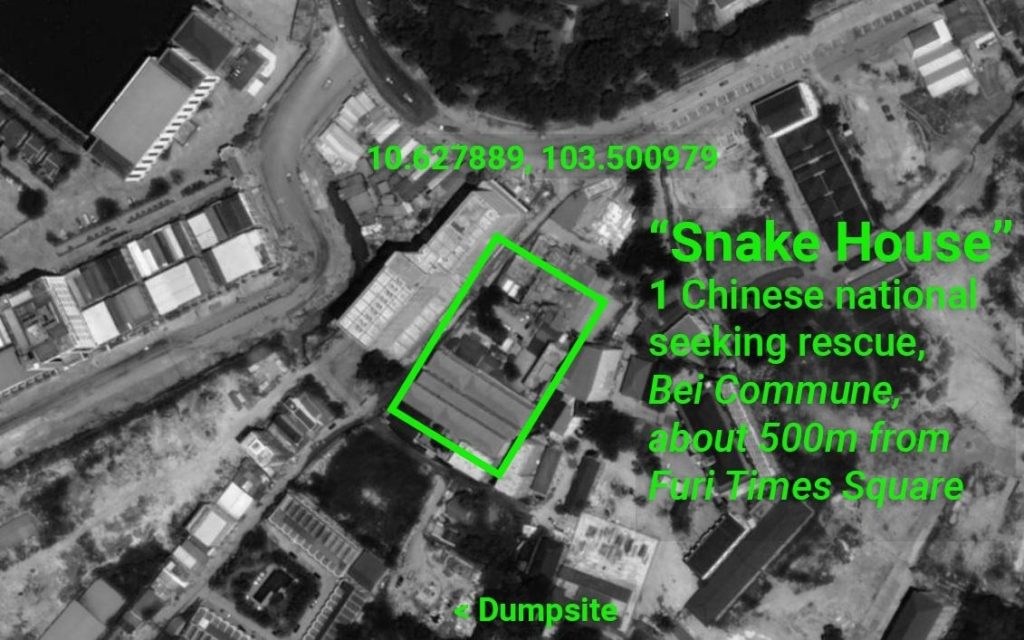

The first was the Bei commune police station, to report three locations in the commune: a small gated building across from a garbage dump, a towering white complex overlooking Sihanoukville’s Independence Park, and the Victory Paradise casino complex.

An officer at the Bei commune station listened to Lu’s requests for intervention, translated into Khmer by a reporter, and responded that some of the companies lend money to bring workers into Cambodia, so they’re obligated to stay with the company. He suggested they were allowed to detain workers on company premises.

“Sometimes the workplace does not allow [workers] to get out, so when they go to work, they cannot get out,” he said. “When you get out, it means you stop working there.”

Lu and reporters then went to the Buon commune station, which was humming with foreigners and citizens waiting for assistance from officers. The commune’s police chief Sam Prak quickly directed the group to the municipal police: “Do not waste time. Go to the city police and they have capability to handle the case. In there, there is a team that can speak Chinese and they have procedures there.”

When asked to file a complaint about Chinese workers detained in his commune, a Muoy commune police officer sitting in the station late in the afternoon asked questions about the complaint but then directed reporters to file the issue to the municipal police.

Reporters showed the officer the compound, and though the officer confirmed it was inside his commune, he disagreed that it was detaining workers. He said it would be difficult for their small staff to enter the compound without approval from officers at the city.

“This location has been operating for a long time, but this is not detention, and sometimes we have taken their money and it’s related to work that they do not allow [workers] out.”

The group visited municipal police toward the end of the trip, spending more than an hour at the station. An officer probed Lu on why he came to file these reports if he wasn’t related to these victims, and he responded that he did this voluntarily. The officer kept asking if he had a boss above him, but Lu insisted he was working alone.

“How generous, coming to help,” the officer said.

An officer first grilled Lu about why he had come to the police office in Khmer, with a reporter translating, and then brought in another officer who could speak Mandarin to ask Lu’s purpose.

After the police visits, Lu expressed frustration, but agreed to go report to the immigration police at the provincial police station the next day.

“Police tell me not to come again because I already help so many people,” he said. But when a reporter asked if he felt it was risky to go to the immigration police office, Lu said he did not mind the consequences.

“If I’m not going there, how to help them? I just think about it like that.”

Filing a Complaint

Lu went the next day, on June 1, with reporters to the Preah Sihanouk provincial police headquarters, where they were directed to meet the immigration department.

Nub Sambo, of the provincial immigration department, first questioned whether Lu had exact locations of the people he wanted to rescue from different compounds across the city, saying they couldn’t do anything without proper locations.

But then Sambo began questioning Lu’s intentions, saying he had seen him many times and recognized him as part of the organization, likely referring to the China-Cambodia Charity Team. He checked Lu’s passport and wrote down all details, and then took a photo of Lu on his phone.

He added that the China-Cambodia Charity Team had damaged the reputation of Cambodia by publicizing the “blood slave” case.

“You work in the media so you know what is true and fake news,” Sambo told reporters.

He said Lu should go through the embassy instead, but Lu said he’d already done so.

“You do volunteer work, but serve who? And whether you have a boss?” Sambo asked.

Lu insisted he was working alone, and then eventually Sambo began taking down details of each case, noting locations and passport details. Sambo also advised Lu to tell the Chinese Embassy to submit written letters to the Cambodian government requesting intervention, or to fill out a paper form and submit it to the embassy. But he issued a warning as Lu and reporters departed.

“If you take information and disseminate this information without checking, there will be a problem,” he said.

‘Why Don’t They Contact Authorities?’

A Khmer-speaking reporter also helped Lu file the cases to several different hotlines that have been suggested by authorities, including the National Police’s general “117” hotline, the immigration police, and Preah Sihanouk provincial spokesperson Kheang Phearum.

After a reporter filed case information — locations, passports and phone numbers — to the national hotline on May 31, a respondent asked how they were being detained, to which the reporter responded they couldn’t leave the workplace.

The hotline responded that the department had heard of many cases like this, but then implied that this was just the nature of working conditions in some of these foreign-run companies.

“Our side has asked our forces to go down so many times and [the complaint] can be about their working conditions — do you understand, sir?” the hotline respondent asked. “Our side used to go down and the force told us that it was like this and it is not detention. It is OK. I will ask my force to check to see it.”

The hotline then took the locations, saying the information the reporter provided was “good,” and then later referred a reporter to a minor crimes officer in Preah Sihanouk province, who asked a reporter to file it as a court case.

A reporter also asked Kem Sarin, the Interior Ministry’s director of investigations, about the process for filing such complaints, and Sarin also referred him to the provincial police.

Keo Vanthan, the spokesperson for the national immigration department, also called the reporter on June 1, saying that complaints for labor detention should be filed to a provincial police office, or the victims should call the hotline by themselves.

“The victims themselves should file a complaint, and they call the hotline of the provincial police,” Vanthan said, though he also informed reporters of the opposite. “Anyone can file a complaint as long as they know about the case.”

A reporter also filed the case information to Phearum, the provincial spokesman, on May 30, the day before contacting the National Police hotline and visiting Sihanoukville police. Phearum acknowledged the messages, and the hotline noted that the same information had been sent to Phearum.

Phearum responded on June 1 to say that he was working on the case. Then on June 3, he said that the phone numbers submitted by the reporter did not work.

“There is a hotline authority, and why don’t they contact authorities when they have a chance to make a call? [You] should think about this point,” Phearum said.

Snakes and Ladders

Since Lu and reporters filed complaints, none of the 11 people seeking help were able to leave their workplaces. According to Lu, some of the victims faced consequences shortly after the group submitted different complaints to Cambodian authorities.

In the middle of the night on May 30, after cases were filed to the provincial spokesman, Lu found out that the three men he was trying to help inside a Buon commune scam compound had been sold to a new location, though Lu was not sure where they were taken.

Lu later messaged a reporter on June 3, saying that the man detained in Chinatown was forced to record a video saying he did not want to leave the scam company. Police had allegedly notified the park and he was thus forced to retract the complaint to police.

Reporters saw all the buildings where complaining workers were allegedly detained. Some of the compounds had been previously accused of detaining and torturing workers, but others were newly identified locations of alleged scam businesses.

One of the victims Lu had spoken to on WeChat was staying inside the Chinatown area in Sihanoukville’s Buon commune. The Kaibo complex in the area — which has been connected to the recently-deceased Crown Football Club owner Rithy Samnang and other Chinese entrepreneurs — has been frequently named by escaped workers as a hub of online scam companies that allegedly detain and sometimes torture their employees.

Three other victims in Buon commune were staying in a building less than a kilometer away from O’Chheuteal beach, until they were sold, according to Lu. A seller working near the building claimed that they were related.

Another victim shared a location that was directly inside the gated Victory Paradise Resort complex in Bei commune, also called “Old Mountain” in Chinese. According to the Commerce Ministry’s business registry, the complex is owned by one Cambodian national, Seng Sokha, and three Malaysians: Kelvin Ang Wei Ming, Huang Yu Kiung, and Chan Jin Chooi. The group also directs a Bei commune company called Vin Hill International, and some of the directors, including Ang Wei Ming, have donated heavily to Cambodian Red Cross.

Sokha also directs businesses with members of the group and other foreign nationals, including a sugar company called Dietcom, consultancy CMDK Consultants & Services, a short-term accommodation business called Pisal Sambath, and a waste-disposal firm K-Water Bio Tech.

Malaysian national Huang Yu Kiung was among the first batch of entrepreneurs to receive junket licenses from Singapore in 2012. Ang Wei Ming, Yu Kiung and Jin Chooi are all listed as shareholders in a variety of Malaysia-listed companies.

Phan Dech, the Village 3 chief in Bei commune told VOD that the location of the Victory Paradise casino, used to be owned by former Preah Sihanouk provincial governor and later Funcinpec parliamentarian Say Hak, who also had a penchant for ordering military police to evict residents. Prime Minister Hun Sen said in 2009 that Hak had built his home on a “ghost road” where he “cannot live peacefully,” after the governor threw a weeklong house-warming party.

Dech identified one of the scam compounds where one man is detained as a former snake farm. He said it was bought by a tycoon named Ly Kuong in 2019.

Kuong had been named an honorary vice president for Preah Sihanouk’s Cambodian Red Cross branch, and he’s also the owner of the Huang Le Casino, according to a post on the Information Ministry’s website. An oknha named Li Kuong is also listed as the president of the Big House Corporation, and a company called Sea Snake Investment Group, which used to also count Russian businessman Nikolay Doroshenko among its directors.

Doroshenko used to live in Sihanoukville for about two decades before he was briefly jailed amid a dispute with another Russian tycoon over island ownership in 2015.

An officer at Bei commune police station was familiar with one compound across from Independence Park, which is called “CITIC Park” by one victim. He claimed it was a former Cambodian People’s Party headquarters, saying “Huang Le” was the name of the area.

The last location, called “Jincai 5” by two victims detained there in Muoy commune, had unclear ownership. The Muoy commune police officer, who spoke to reporters while Lu visited to alert the office of the case, mentioned it was near land owned by Brigade 70 chief Mao Sophan, but he did not know the exact location where Sophan’s land ended.

Sophan did not answer attempts to call him, while contacts in the Commerce Ministry business registry connected to Sokha and Victory Paradise did not respond.

Kuong, the alleged owner of the snake house and former CPP headquarters, claimed that he was not associated with the buildings that now appear to be operating scam compounds. He called the snake house messy and said he had assisted Russian nationals operate the business in the past, but now he has nothing to do with it.

He made similar comments about the building identified as a former CPP headquarters: “At that time, I was asked to rent it and now I do not rent it anymore.”

Kuong also said he was not involved with a casino called Huang Le, implying he did not want to be associated with it, though an Information Ministry post from one year ago connected him to the casino.

“I do not know it and it belongs to other people, and if we say it wrong, they would curse us,” he said.

By the end of the trip, Lu was deeply worried about one detained man in particular who was kept in Chinatown, and alleged he had been threatened by the scam company to apologize to police on June 3. He asked a reporter to help, adding that he didn’t know what to do.

As reporters and Lu headed back to Phnom Penh on a van days before, Lu said he was not sure what to do next if the police couldn’t help. He took another call from police in China on the van ride back, one of whom told him they should pay him their salary if he could get these people out, Lu recalled to reporters.

A reporter asked Lu what he thought about the whole process on the van ride back.

“I’m just worried about when they can get out,” he replied. “Nothing to think.”

Clarification: Lu’s photo was removed due to safety concerns. The text was also edited to clarify that Lu believed when Sihanoukville police previously asked about money, it was about a scam operation’s ransom.